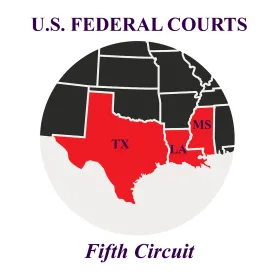

Last month, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the lower court’s March 2021 dismissal in Oklahoma Firefighters Pension and Retirement System v. Six Flags Entertainment Corporation. In the now-revived class action, investors sued Six Flags in relation to 11 Chinese theme parks that Six Flags licensed to a local company for construction and operation, which were expected to be a major driver of Six Flags’ revenue growth – before construction stalled and the licenses were ultimately cancelled in February 2020, these Chinese parks were expected to contribute up to $60 million in pre-tax profits to Six Flags. In the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, the Court ruled that the lower court had excessively discounted the Complaint’s factual allegations, and that the Complaint did, in fact, sufficiently allege material misstatements and scienter.

The Lower Court Applied Too Heavy a Discount to Confidential Witness Testimony

The Complaint was primarily based on testimony from a confidential witness: an employee who oversaw construction of the Chinese parks, on Six Flags’ behalf. The lower court’s opinion heavily discounted this witness’ testimony throughout its analysis, on account of his confidentiality. However, while the Fifth Circuit acknowledged that confidential witness testimony should be discounted in some fashion, it also chastised the lower court that applying a “discount” to witness testimony “does not mean unfettered discretion to discard” that testimony.

Instead, the Fifth Circuit explained that “[t]he degree of discounting depends on the circumstances involved.” It went on to explain that the circumstances here support only a “minimal” discount, because it was plainly alleged that the confidential witness was in such a position as to have direct knowledge supporting his offered testimony. For example, the Complaint described the confidential witness as:

-

a Six Flags employee, holding the title of “International Director of International Construction and Project Management”;

-

having responsibility for “overseeing the construction of the China parks and reporting internally on their progress”;

-

working onsite at certain China park locations, and performing inspections of the construction’s progress (or lack of progress); and

-

attending meetings with management from Six Flags and its Chinese construction partners, including meetings where the Chinese partners discussed construction delays and problems.

In fact, given these myriad allegations and the witness’ high-ranking position at Six Flags, the Fifth Circuit went so far as to “wonder just how unknown”—i.e., how “confidential”—the witness really is to each of the parties.

Moreover, as described in the Complaint, the witness was so engrained in the Chinese parks’ construction that he even possessed insight into the Chinese construction partner’s finances. In this regard, the Complaint alleges that representatives of the Chinese partner told the witness that the partner wasn’t paying vendors, couldn’t afford construction blueprints, was forcing staff to resign, and owed three months of back-pay to its employees. And the witness’ allegations were further supported by aerial photos showing a lack of construction progress, and contrasting images of (a) a barren Chinese Six Flags location (Zhejiang), taken 19 months before its scheduled opening, with (b) progress at a Chinese Disneyland location (Shanghai), taken 24 months before its opening:

|

(a) Six Flags (Zhejiang) |

(b) Disneyland (Shanghai) |

|

|

|

The Complaint Sufficiently Alleged Material Misrepresentations, Even if it Were Technically Possible for the Parks to Open On Time

After describing the weight properly given to the confidential witness’ testimony, the Fifth Circuit determined that the Complaint sufficiently pled material misrepresentations or misstatements by Six Flags with respect to statements made prior to October 2019, when it started adding certain cautionary language alongside its statements. To this end, whereas the lower court believed that the Complaint failed to show misstatements because it did not demonstrate that Six Flags’ stated construction timelines were necessarily unattainable, the Fifth Circuit rejected the lower court’s premise that the Complaint was required to include facts showing that Six Flags’ stated timelines were “categorically impossible.” Instead, the Fifth Circuit explained that the Complaint need only plead facts sufficient to show that a deadline was “highly unlikely,” and then went on to determine that the Complaint met this “highly unlikely” standard.

Specifically, the Complaint alleged that the timeline was “highly unlikely” through at least four factual allegations: (1) that less than two years pre-opening, the Chinese construction partner had still not commissioned construction blueprints, and didn’t have enough money to commission them; (2) that the Chinese partner lacked the money to commission the manufacture of rides; (3) that ride-makers required long lead times in order to design the bespoke rides, which would necessarily push ride construction past the stated opening dates; and (4) the inclusion of the aerial photographs comparing the derelict pre-opening Six Flags location with prolific pre-opening construction at the Disneyland location. To these factual allegations, the Complaint also added the potentially-expert assessment of the confidential witness himself and, although Six Flags is free to challenge whether that witness’ “expertise” is sufficient or whether his assessment is accurate, the Fifth Circuit explained that those arguments are questions of fact not appropriately resolved at the Motion to Dismiss stage.

The Complaint Alleged Scienter, Because Executives Were Alleged to Have Both Motive and Knowledge

Finally, the Fifth Circuit determined that the Complaint sufficiently alleged scienter, because it alleged that Six Flags executives had a motive to mislead investors and reasons to know that their stated timelines were misleading or false.

-

With respect to motive, at the time of Six Flags’ pre-2019 misstatements, the company offered a special bonus to its executives if the company’s pre-tax earnings reached $600 million. This bonus was substantial: if 2018 earnings met the target, executives would earn stock grants worth between 300% and 600% of their base salaries. As it turns out, the Chinese parks were a necessary component to reaching this $600 million target, which would provide a substantial motive for the executives to mislead investors. And although this profit motive no longer existed for statements that Six Flags made after the start of 2019, executives during this later time period would still be “plausibly motivated by a desire to save face regarding the parks.”

-

With respect to knowledge, the Complaint sufficiently pled that executives knew their stated timelines were unattainable, because the confidential witness (i) gave weekly reports to his superiors, the contents of which were passed along to the Board of Directors; (ii) drafted “Master Reports,” which were specifically created for presentation to the Board of Directors; and (iii) penned a detailed letter to HR, explaining his concerns regarding the Chinese parks’ inabilities to meet the stated construction timelines.

In addition to pleading motive and knowledge, the Complaint also alleged that the Chinese parks were a significant part of Six Flags’ business (with the 11 Chinese parks expected to add 20–40% to Six Flags’ EBITDA). As the Fifth Circuit explained, although these allegations are insufficient to support a stand-alone “core operations” theory of scienter, they do provide additional support for the Complaint’s other scienter allegations.

Lessons Learned: Confidential Witnesses Matter, and Projected Timelines Can be Misstatements

The Fifth Circuit’s opinion contains several important lessons. First and foremost, although courts often discount allegations based on confidential witnesses, this opinion underscores that it is the circumstances surrounding confidentiality – not the mere fact that a witness’ name is withheld – that warrants discounting. And second, although project timelines are inherently subject to delay, this does not insulate companies from liability if they tout timelines that they know have become unrealistic.

/>i

/>i