In a significant departure from the general downward trend in False Claims Act1 (FCA) civil fraud recoveries over the past half-decade2—and as predicted last year3—recoveries in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 drastically increased compared to those in FY 2020. The US$5.6 billion in recoveries reported by the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) in its 1 February 2022 press release is more than double the US$2.2 billion recovered in FY 2020, and is the second largest total recovery ever recorded.4 Yet again, the health care industry was far and away the primary driver of civil fraud enforcement activity, accounting for 90% of total recoveries—over US$5 billion.5 Notably, health care civil fraud recoveries in FY 2021 were the highest ever in a single year by a large margin, representing nearly US$2 billion more than the previous high reported in FY 2012 (and over US$3 billion more than FY 2020).6 As expected, aggregate recoveries were much greater in qui tam matters in which the DOJ participated, either by filing its own complaint, intervening in relators’ qui tam actions, or otherwise pursuing a recovery.7 This fact held true for all qui tam activity generally, and for health care matters in particular.8

The substantial increase in civil fraud recoveries in FY 2021 is due, in large part, to the highly publicized US$2.8 billion settlement with Purdue Pharma in connection with the opioid manufacturer’s marketing and sales practices.9 However, even setting aside the latter recovery, by virtually any measure, FY 2021 was marked by heavy heath care-related FCA activity. The government did not discriminate in its enforcement across the health care industry, as it targeted insurers,10 health care systems,11 medical suppliers,12 pain clinics,13 clinical laboratories,14 substance abuse centers,15 pharmaceutical companies,16 psychiatric facilities,17 home health agencies,18 and hospitals19 (among others) with its enforcement efforts. The DOJ has, again, expressed its intent to pursue health care fraud diligently, touting its “vigorous pursuit of health care fraud” as instrumental in “restor[ing] funds to federal programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE” and “prevent[ing] billions more in losses by deterring others who might try to cheat the system for their own gain,” as well as “protect[ing] patients from medically unnecessary or potentially harmful actions.”20

Looking ahead to FY 2022, K&L Gates LLP perceives three areas to be particularly worthy of attention. First, Congress appears primed to consider legislation that would significantly amend the FCA to make it more difficult for defendants to assert materiality defenses pursuant to Escobar21 and its progeny and for the government to dismiss qui tam actions over relators’ objections.22 Second, FCA actions predicated on the use of Electronic Health Record systems (EHRs) against vendors and providers are likely to substantially increase. And, third, industry participants should expect the DOJ to accelerate its pursuit of fraud in the Medicare Advantage arena against both insurers and providers. This article will first examine the statistics underlying FCA activity in FY 2021, and will then explore these three areas in depth.

FY 2021 Civil Fraud Recoveries

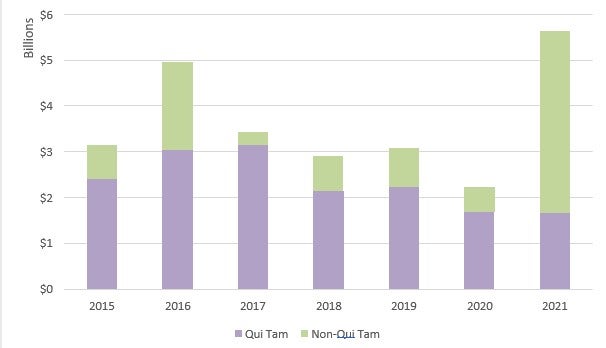

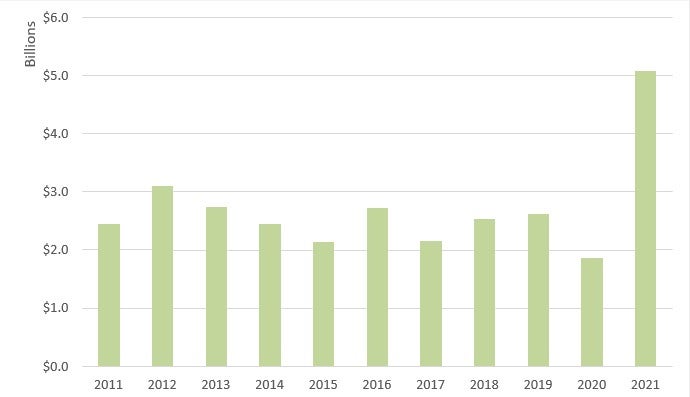

In FY 2021, the government obtained more than US$5.6 billion in FCA settlements and judgments, the second-highest recovery ever and the highest recovery since 2014.23 This amounts to an increase of US$3.2 billion from the US$2.2 billion collected in FY 2020.24 Unlike in previous years, non-qui tam matters drove the bulk of the recoveries in FY 2021 due to several large settlements with pharmaceutical manufacturers in connection with the opioid crisis.25 However, whistleblower and qui tam-related recoveries remained strong, bringing in over US$1.6 billion. 26

Recoveries in the healthcare industry increased dramatically in FY 2021.28 Specifically, the government recovered over US$5 billion in civil fraud-related actions involving the health care industry in FY 2021, compared to only US$1.8 billion recovered in FY 2020.29 The increase is due, in significant part, to several large settlements with pharmaceutical manufacturers related to the opioid crisis, including a US$2.8 billion settlement with Purdue Pharma.30 FY 2021 recoveries in health care represented approximately 89% of all recoveries.31

Considering only qui tam actions in which the government intervened, FY 2020 recoveries from interventions totaled over US$1.1 billion.33 In contrast, recoveries from non-intervened cases amounted to over US$479 million.34 Of the US$1.1 billion recovered in intervened cases, approximately US$1 billion involved the health care industry.35 As illustrated in the graph at Figure 3, from FY 2015 to FY 2021, total recoveries from qui tam actions in which the government intervened have generally declined.36 Recoveries in healthcare-related actions where the government intervened also slightly decreased from approximately US$1.28 billion in FY 2020 to approximately US$1 billion in FY 2021.37 Despite these recent declines in recoveries, efforts to combat fraud in health care remain robust, and government intervention remains the driving force behind the vast majority of civil fraud recoveries inside and outside of health care.

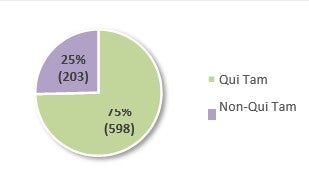

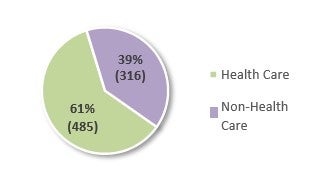

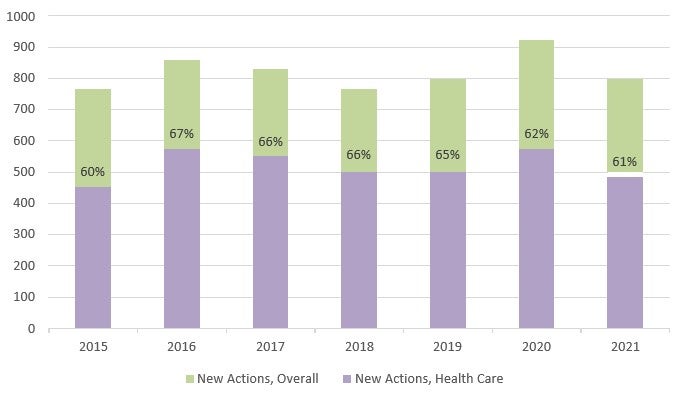

The use of the FCA primarily in health care is also evident in the number of FCA actions filed last year.38 In FY 2021, 801 new FCA actions were filed, 598 of which were qui tam or whistleblower actions (which amounts to an average of approximately twelve (12) new qui tam cases per week).39 Of the 801 new FCA actions, 485—or 61%—were related to the health care industry, which represents a small decline from 62% in FY 2020.40 Non-qui tam actions in the health care industry also decreased approximately 20% since FY 2020.41

Filed in FY 202143

The number of new FCA actions decreased slightly in FY 2021, although the number of new healthcare-related actions per year has not changed significantly since 2015.45 The consistency in the number of actions filed each year is remarkable in light of the increased number of non-qui tam actions and the marked increase in recoveries in FY 2021. These numbers may suggest that the average settlement amounts or assessed damages/penalties are decreasing for qui tam matters or that FCA claims are generally less successful overall.

Alternatively, the increased number in government-initiated enforcement actions may not result in increased civil fraud recoveries until later fiscal years. For instance, in FY 2021, the government settled claims with Purdue Pharma for approximately US$2.8 billion, contributing greatly to the marked increase in recoveries. This resolution came after years of investigation by the DOJ and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The same trend appears to be the case for the health care industry in FY 2021.

In part due to several large, one-time settlements with pharmaceutical manufacturers, FY 2021 reversed the trend of declines in FCA recoveries. While it is currently unclear whether FY 2022 will be able to match the significant recoveries in FY 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to stabilize, there will likely be additional opportunities in FY 2022 for relators to continue to allege improper receipt, use, or retention of government funds.

Moreover, the government continues to expand the reach of its FCA investigations in health care to new and more diverse areas. As such, the government and relators are likely to continue to aggressively use the FCA in the health care sector, signaling that the spike in civil fraud recoveries in FY 2021 may prove less an aberration and more a harbinger of increased enforcement.

2022 Outlook

FCA-related actions in healthcare in FY 2022 are likely to continue the substantial trend of government recoveries that has helped define the last decade of government enforcement. In particular, the following three areas appear particularly positioned for significant FCA legal development or increased relator and government enforcement activity in FY 2022:

-

Potentially increased litigation costs for health care entities and providers due to the introduction of the FCA Amendments of 2021 in the U.S. Senate;

-

EHR-related enforcement, including actions related to requirements under the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program;46 and

-

Medicare Advantage-related enforcement, including actions related to the calculation of risk adjustment scores.

These areas are discussed in detail below, along with their potential effect on FCA recoveries and the overall enforcement environment in 2022 and beyond.

False Claims Amendments Act of 2021 Is Primed to Raise Healthcare Litigation Costs

The U.S. Senate may soon take up proposed amendments to the FCA that would alter the FCA’s materiality standard and the government’s ability to dismiss qui tam actions over relators’ objections. Specifically, if it becomes law,47 the False Claims Amendments Act of 2021 (FCAA) would make it harder for defendants to prevail in FCA actions and could also make it more difficult for the government to dismiss qui tam actions it views as meritless. Importantly, such changes would likely result in higher litigation costs for health care entities and providers defending against FCA actions.

In July 2021, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), with broad bipartisan support, introduced new legislation to amend the FCA.48 Senator Grassley’s proposal sought four major changes to the FCA: i) lowering the burden of proof for proving materiality to a preponderance of the evidence, and then shifting the burden to defendants to rebut the argument of materiality with “clear and convincing evidence;” ii) shifting the government’s costs for responding to discovery requests in non-intervened qui tam actions to defendants; iii) requiring the government to demonstrate its reasons for dismissing qui tam actions over relators’ objections, after which relators would have the opportunity to show that such reasons are fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or contrary to law; and iv) clarifying that the FCA’s Anti- Retaliation provision extends to post-employment retaliation.49

However, in November 2021, the Senate Judiciary Committee significantly altered the proposed bill, rejecting the fee-shifting provision for non-intervened cases, while also adopting wholesale the extension of the Anti-Retaliation provision.50 Notably, the amended legislation also takes a more narrowed approach to modifying the materiality standard than Senator Grassley’s version, and proposes that “the decision of the Government to forego a refund or to pay a claim despite actual knowledge of fraud or falsity shall not be considered dispositive if other reasons exist” for the government’s decision.51 This change effectively rebuffs the Supreme Court’s holding in Escobar,52 while also avoiding the adoption of a complex standard of proof that may be impractical to implement in reality.

The amended bill also offers a different standard for governmental dismissal of FCA actions over relators’ objections than that set forth in Senator Grassley’s proposal.53 The modified standard in the amended bill would require the government to articulate a “valid government purpose and a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose” in order to jettison relators’ qui tam complaints without their consent, essentially imposing on the government the familiar rational-basis review standard from constitutional jurisprudence.54 This change seems to target the so-called “Granston Memo,” a Federal Circuit Court split, and the perception amongst some members of Congress that recent DOJ guidance and judicial action have made it easier for the DOJ to unilaterally dismiss relators’ complaints at or near their inception.

Even though the amended legislation is narrower than Senator Grassley’s original version, it still has potentially far-reaching impacts on defendants’ opportunities to dispose of FCA actions earlier in their life cycles. Congress’s efforts to foreclose such avenues for defendants, in turn, have the potential to significantly drive increased litigation costs for those operating in health care.

The FCAA Has Escobar Squarely Within Its Sights

Senator Grassley—who was instrumental in modernizing the FCA over the last few decades—appears largely driven to offer his proposed changes to the FCA in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar.55 Escobar held, in pertinent part, that the government’s payment of a particular claim when it has actual knowledge that certain requirements were violated is strong evidence that those requirements were not material to payment.56 Many have perceived the decision as making it easier for defendants to escape FCA liability by challenging materiality, even at the motion to dismiss stage.

In promoting the FCAA, Senator Grassley and other members of Congress have voiced frustration about the perceived effects of Escobar. For example, Senator Grassley recently contended that the FCAA will help “clarify[] confusion after the Escobar case” and will “significantly improve the process for smaller [FCA] claims.”57 He also suggested that the legislation will better “protect taxpayers and whistleblowers who shine a light on fraud, waste and abuse.”58 Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vermont) has added, in reference to Escobar, that, “[i]n 2016, the Supreme Court weakened this critical tool [the FCA] by making it more difficult for plaintiffs and whistleblowers to succeed in lawsuits against government contractors engaged in fraud.”59 These and other senators supportive of the FCAA have also bluntly stated that Escobar “has made it all too easy for fraudsters to argue that their obvious fraud was not material simply because the government continued payment.”60

It seems clear from these statements that the central aim of the FCAA is to reverse what some members of Congress view as a defendant-favorable decision in Escobar and make it easier for whistleblowers and the Government to succeed in FCA litigation.61 The broad phrasing—“if other reasons exist”—in the proposed legislation seems designed to prevent defendants in FCA litigation from finding a viable exit from cases at the motion to dismiss or motion for summary judgment stages on materiality grounds alone. Courts, of course, will determine the scope and meaning of this phrase, as well as the limits of its application, if the legislation passes.

If passed, how the FCAA’s new materiality standard will be judicially interpreted and what its impact will be in FCA litigation will take years to develop. In the meantime, litigation costs will likely increase as defendants seek to discover what the government knew and when it knew it, in attempting to foreclose any assertion that “other reasons exist[ed]” for the government’s continued payment of claims. Ultimately, the proposed changes to the materiality standard threaten to slow the momentum from defendants’ hard-earned judicial gains in this area in the last several years. However, the full scope of this impact is to be determined.

Legislative Resolution of a Circuit Split

The proposal to raise the standard for government dismissals of potentially meritless FCA cases over relators’ objections also survived the Judiciary Committee—albeit in modified form—and is another development to monitor in 2022. The FCAA, as advanced, would require the government to “identify a valid government purpose and a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of that purpose” when seeking dismissal under § 3730(c)(2)(A) of the FCA.62 The burden would then shift to the relator bringing the qui tam action to demonstrate that the “dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.”63

If enacted, this specific change to the FCA would effectively resolve the current circuit split on the government’s dismissal authority in FCA cases. Currently, there are at least three different standards governing this authority. The D.C. Circuit has held that the government has an “unfettered right to dismiss” a qui tam action under § 3730(c)(2)(A).64 In contrast, the Seventh Circuit requires that the government establish “good cause” to intervene, and then satisfy the voluntary dismissal standards under Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in order to dismiss over a relator’s objection.65 The Ninth Circuit mandates that the government identify “a valid government purpose” and “a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose” to effectuate dismissal, after which the burden shifts to the relator “to demonstrate that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.”66 The proposed changes outlined in the FCAA essentially adopt the Ninth Circuit’s test.

The DOJ’s view of its authority to dismiss qui tam actions is encapsulated in the so-called “Granston Memo” released in 2018.67 In the Granston Memo, the DOJ expressly states that “the appropriate standard for dismissal under § 3730(c)(2)(A) is the ‘unfettered’ discretion standard adopted by the D.C. Circuit rather than the ‘rational basis’ test adopted by the Ninth and Tenth circuits.”68 Senator Grassley has been critical of the Granston Memo for years. In a 2019 letter to then-Attorney General William Barr, Senator Grassley criticized the DOJ’s implementation of the Granston Memo and the DOJ’s dismissal of qui tam cases for allegedly “vague and at times questionable concerns over prerogatives or limited government resources.”69 Senator Grassley asserted that “[s]uch actions could undermine the purpose of the False Claims Act by discouraging whistleblowers and dismissing potentially serious fraud on the taxpayers.”70

In December of 2019, then-Assistant Attorney General Stephen Boyd responded to Senator Grassley’s letter, and disavowed the Senator’s perception that the DOJ was engaging in widespread dismissals under § 3730(c)(2)(A).71 Boyd asserted that, out of 1,170 qui tam actions filed since the Granston Memo, the DOJ only sought dismissal in 45 of them, which translates to less than 4% of the actions.72 Despite the statistics showing that § 3730(c)(2)(A) dismissals are infrequent, Senator Grassley previewed in February 2021 that Congressional action would address the DOJ’s view that it has “unfettered and unchecked discretion” in this area.73 Criticizing the DOJ’s view in a letter to then-Attorney General Nominee Merrick Garland, Senator Grassley wrote, “[t]he Justice Department is not, and cannot be, the judge, jury, and executioner of a relator’s claim.”74 In this way, the FCAA seems to function as a legislative solution to a perceived issue that has been historically left to the executive and judicial branches.

If it becomes law, the FCAA’s resolution of this circuit split will make it more difficult for the government to unilaterally dismiss a qui tam action due to added burden of doing so. As a result, actions that could have been previously disposed of at an early stage of litigation would likely progress. However, given how infrequently the DOJ has used its dismissal authority under the FCA over the last several years—and despite the guidance in the Granston Memo—the practical effect of this aspect of the FCAA is an open question.

Organizations, Including the AHA, Express Opposition to the FCAA

Many organizations have already taken notice of the increased costs that would result from the FCAA, arguing that the proposed legislation would make it harder to dispose of meritless FCA claims, leading to undue settlements and higher health care costs due to increased litigation.75 Twenty-five organizations who strongly oppose the FCAA, including the American Hospital Association, the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, and the Federation of American Hospitals, sent a letter to Senators Grassley and Dick Durbin voicing their concerns about the bill.76 In that letter, the organizations express fear that the FCAA would exacerbate the already existing problem of excessive FCA litigation.77

The letter highlighted support for the materiality standard adopted by the Supreme Court in Escobar, which sought to dissuade use of the FCA to punish “garden-variety breaches of contract or regulatory violations” and declined to adopt the expansive view that any statutory, regulatory, or contractual violation is material if the defendant knows the government would refuse payment were it made aware of the violation.78 The opposition letter expressed concern that undermining the rigorous test for materiality outlined in Escobar would make it more difficult to dispose of meritless FCA cases without significant expense.79 The group also voiced concern that the new standard limiting the government’s ability to dismiss qui tam cases it views as meritless would significantly narrow a power the DOJ already sparingly uses.80 Whether such pointed opposition from the health care industry will have an effect on whether the FCAA advances further is yet another issue to watch in the coming year.

EHR-Related FCA Enforcement

As alluded to in the DOJ’s 1 February 2022 press release announcing the FY 2021 civil fraud recoveries, increased FCA enforcement in the EHR space in the coming year is probable.81 EHRs provide comprehensive real-time patient medical information in an electronic format that providers can access instantly and securely for the management of patients’ treatment. In recent years, EHR use has become widespread, in large part due to government initiatives such as the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, which provided over US$35 billion in incentives to promote and expand the adoption and use of EHRs by eligible hospitals and providers.82 One such incentive, the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program (previously known as the Medicare EHR Incentive Program),83 contains specific requirements—commonly referred to as “meaningful use” requirements— related to the use of EHR technology to improve the quality, safety, and efficiency of patient care.84 While they are integral to health care delivery today, EHRs carry elevated risk for FCA liability (as well as potential criminal liability) because of their potential for misuse.

To date, the DOJ’s EHR-related enforcement has been varied in nature. However, one thing is clear: from straightforward false claims submissions, to false certification, to FCA actions predicated on federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) culpability,85 the DOJ will not hesitate to impose FCA liability for EHR-related fraud in all its forms. In fact, the DOJ has recently emphasized how “complex EHR-related fraud schemes remain a focus of the Department’s work.”86

For instance, in January 2021, the DOJ announced that Athenahealth, Inc. (Athena), an EHR vendor, agreed to pay monetary penalties in the amount of US$18.25 million to settle FCA and AKS violations.87 Following the filing of a qui tam complaint, the DOJ filed a complaint in intervention against Athena alleging that Athena paid kickbacks to healthcare providers and other EHR vendors to induce them to purchase and recommend Athena’s EHR technology.88 Through the exchange of illegal remuneration in contravention of the AKS, Athena allegedly knowingly submitted and caused its clients to submit false claims for EHR Incentive Program payments, resulting in millions of dollars in Medicare and Medicaid incentives that were not payable.89 The Athena matter makes clear that EHR vendors should carefully consider their provider marketing programs, especially given the DOJ’s recent signaling of its focus on EHR-related enforcement actions.

The DOJ has also brought cases targeting EHR vendors that have allegedly manipulated bona fide EHR functionality, causing end-users to submit false claims to federal health care programs. For example, in January 2020, the DOJ filed a criminal information against Practice Fusion, Inc., another EHR vendor, charging it with soliciting and receiving kickbacks in the form of “sponsorship payments” from pharmaceutical companies in exchange for allowing them to participate in the design and development of clinical decision support alerts embedded in Practice Fusion’s EHR software.90 The alerts were allegedly designed to increase prescriptions for the pharmaceutical companies’ products.91 Practice Fusion also allegedly caused health care providers to submit false claims for federal incentive payments by misrepresenting the data portability capabilities of its EHR software, giving rise to separate FCA allegations.92 For these alleged violations, Practice Fusion entered into a deferred prosecution agreement in which it agreed to pay nearly US$26 million in criminal fines and the forfeiture of criminal proceeds, as well as civil penalties of over US$118 million to settle FCA violations.93

Another line of EHR-related enforcement cases has involved the functionality of EHR software itself, as opposed to the manner in which end-users employ the software’s features; namely, where EHR vendors obtain certification through alleged fraud or misrepresentation. For instance, in February 2019, the DOJ filed a complaint against Greenway Health, LLC (Greenway) alleging that it falsely obtained EHR Incentive Program certification by misrepresenting the capabilities of its Prime Suite EHR and paid kickbacks to users who recommended its product.94 Greenway’s alleged failure to meet certification requirements prevented health care providers using Greenway’s EHR from meeting meaningful use requirements.95 Greenway agreed to pay US$57.25 million to settle these allegations, and entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement (CIA) requiring it to retain an outside entity to assess its quality control and compliance systems and to review its arrangements with health care providers to ensure AKS compliance.96

Likewise, in May 2017, the DOJ announced a settlement with eClinicalWorks, LLC (ECW) to resolve FCA and AKS violations in connection with ECW’s alleged misrepresentation of its EHR software capabilities and payment of kickbacks to customers that promoted its product.97 ECW allegedly failed to satisfy the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology certification criteria and made false statements in obtaining certification by concealing that its software did not comply with certification requirements.98 These failures allegedly caused customers to submit false claims for federal incentive payments based on their use of ECW’s software.99 As part of the settlement, ECW agreed to pay US$155 million and enter into a five-year CIA, which required it to retain an independent software quality oversight organization to assess its software quality control systems, among other provisions.100

Looking forward to FY 2022, we expect an uptick in EHR-related FCA activity. In each of FY 2019,101 2020,102 and 2021,103 the DOJ has emphasized that EHR usage and arrangements remain areas of focus, portending increased enforcement as EHR use grows ever more prevalent and as EHR incentive payments increase. As the case summaries above demonstrate, recent civil fraud recovery efforts affecting EHRs have not relied on any one legal theory; they have addressed marketing practices,104 software functionality,105 and incentive payment certification.106 Health industry participants should expect whistleblowers and the DOJ to continue pursuing novel theories in pursuit of FCA recoveries. As such, EHR vendors should be aware that, regardless of how payments are characterized, any person or entity that offers remuneration (as broadly defined by the AKS) to current or potential customers for the referral of business—even EHR system business—will be subject to intense scrutiny. Moreover, it is critical that hospitals and providers thoroughly evaluate EHR vendors and their products prior to entering into arrangements for the development or provision of EHRs. If the EHR software does not comport with meaningful use requirements, providers using such EHRs cannot attest to Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program compliance, as doing so could create FCA or criminal liability. The AKS (and by extension, the FCA) applies in full force in these cases.

Medicare Advantage FCA Enforcement

Another area ripe for increased FCA enforcement in the coming year and beyond is the Medicare Advantage (MA) program, also known as Medicare Part C.107 While MA-related FCA inquiries have persisted for some time, increased enforcement in FY 2022 is likely given the DOJ’s recent assertion that this area is an “important priority for the department.”108 The MA program is already very large and continues to expand, with the Congressional Budget Office projecting that total enrollment will grow from 24 to 26 million enrollees in FY 2022, with total outlays ballooning from US$343 million to US$417 million.109 Given the number of federal dollars at stake in this arena, providers and health plans should expect enforcement activity to increase concomitantly with continued MA program growth.

As an alternative to traditional Medicare, beneficiaries may enroll in Medicare Advantage Plans (MA Plans), which are health plans offered by private insurers known as Medicare Advantage Organizations (MAOs).110 Unlike traditional Medicare—where the federal government pays healthcare providers directly for beneficiaries’ treatment—under MA, the government makes monthly capitation payments to MAOs, which use those proceeds to pay for their enrollees’ covered services pursuant to rates they negotiate directly with health care providers.111

To determine the amount of capitation payments, the government starts by paying each MAO a monthly predetermined base rate—known as a “per-member, per-month” payment— which varies for each MA plan depending on a number of factors.112 Additionally, in a process known as “risk adjustment,” the government annually adjusts this per-member, per- month payment for each beneficiary by assigning an individual risk score to account for that patient’s demographics and health status.113 The higher the risk score, the higher the payment. In calculating a MA Plan’s risk adjustment, the government relies on MAOs and physicians to correctly document and submit diagnosis codes.114

Increasingly, the DOJ has scrutinized the manner in which MAOs, providers, and vendors report risk adjustment data, as there is concern that entities may seek to artificially inflate patient risk scores in order to receive greater reimbursement from the government. This scrutiny has resulted in increased FCA enforcement activity in the MA arena, which will require providers and health plans to scrutinize their reporting practices to mitigate against potentially exorbitant FCA exposure or exclusion from the federal health care programs.

For instance, in October 2021, the DOJ filed a complaint in intervention against a large health care system in the Western United States (the “Health System”), alleging it secured more than US$1 billion in excess MA proceeds to which it was not entitled in contravention of the FCA.115 Specifically, the DOJ alleged that the Health System facilitated the addition of diagnosis codes to patient medical records retrospectively, where the diagnosis purportedly did not exist or was unrelated to the patient’s visit, in order to increase reimbursement from Medicare.116 The DOJ alleged that the Health System achieved this end principally through two practices: data mining117 and retrospective chart reviews,118 the latter of which the DOJ faulted the Health System for allegedly instructing reviewers “to identify only potential new diagnoses”119 (commonly known as a “one-way review”).120 Plans and providers should follow developments in this matter closely, as this case directly implicates the propriety of widely used coding practices that impact risk adjustment.

The DOJ’s intervention in that case followed its intervention in an FCA lawsuit against Independent Health the month prior, which was also predicated on the submission of allegedly inaccurate health status information of MA beneficiaries to prompt increased Medicare reimbursement.121 Likewise, in August 2021, the DOJ announced a settlement with Sutter Health in which Sutter agreed to pay US$90 million to resolve FCA allegations pertaining to its submission of inaccurate diagnosis codes.122 In addition, in October 2018, DaVita Medical Holdings agreed to pay US$270 million to resolve similar claims.123 These cases portend increased FCA enforcement in the MA arena due to the DOJ’s keen interest on reining in risk adjustment practices. The DOJ is primed to pursue insurers, providers, and vendors alike in its scrutiny of methods designed to capture additional diagnoses which would increase payments through the risk adjustment process.

The DOJ has also sought to impose FCA liability where there is an alleged failure to conduct “two-way” chart reviews. For example, in March 2020, it filed an FCA suit against Anthem, Inc. in connection with Anthem’s engagement of a vendor to conduct retrospective chart reviews.124 In doing so, the government faulted the insurer for failing to delete unsupported diagnosis codes contemporaneously with its efforts to add additional codes. According to the government, the additional codes yielded by Anthem’s chart review generated more than US$100 million per year, but this amount would be reduced by over 70% if a two-way review were undertaken.125 The DOJ lodged analogous claims in the Independent Health suit discussed previously,126 as well as against UnitedHealth in a pending suit filed in May 2017.127

Given the DOJ’s aggressive enforcement in the MA arena over the past several years, we expect FY 2022 to be a busy year for MA-related FCA activity. Again, as recently as February of this year, the DOJ has proclaimed its commitment to such efforts.128 This reality is especially concerning for providers, as the DOJ and whistleblowers appear to be focused on practices that are not expressly required or forbidden, and are arguably legitimate. For example, while there is no specific requirement to conduct two-way chart reviews (or prohibition on conducting one-way reviews), the weight of treble damages under the FCA and potential exclusion from federal health care programs will loom large if a company finds itself in the DOJ’s crosshairs based on this legal theory. MA Plans, health care providers, and vendors should evaluate their Medicare compliance programs and ensure they are comporting themselves with evolving best practices. Still, given the dearth of legal and regulatory authority in this area, MA stakeholders are in a difficult position. On this score, one of the sharpest arrows in FCA defendants’ quivers may be the Supreme Court of the United States’ 2019 Allina decision 129 and its progeny,130 which—as K&L Gates underscored last year131—could potentially undermine the government’s ability to predicate liability on sub- regulatory guidance. However, whether Allina and related cases have an impact in MA cases will likely depend on litigation in FY 2022 and beyond.

Conclusion

FY 2021 was a nearly unprecedented year in terms of FCA recovery, particularly in the health care space. Although several large settlements related to the opioid crisis primarily drove the amount recovered, FY 2022 will undoubtedly bring significant FCA activity action in health care, as enforcement in this area has remained largely consistent for well over a decade. Additionally, pending amendments to the FCA which recently passed through the Judiciary Committee, may drive health care litigation costs in FY 2022 and beyond. And, as discussed above, the government and relators continue to expand the frontier of FCA enforcement to respond to new trends in health care. Specifically for FY 2022, hospitals and providers should be prepared to face regulatory scrutiny in connection with EHR implementation and MA billing, among other areas.

Accordingly, it is essential for those operating in health care—particularly those that bill federal and state health care programs—to now, more than ever, ensure their financial arrangements and billing activities are compliant with applicable federal and state health care fraud and abuse laws. Accordingly, those operating in health care should work with health care regulatory counsel to design, implement, and enforce properly functioning compliance programs and other efforts to best avoid FCA exposure, costly litigation, and penalties.

ENDNOTES

1 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729 - 3733.

2 Civil fraud recoveries dropped from a high of US$5 billion in FY 2016 to US$2.3 billion in FY 2020. U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

3 Mark A. Rush, Mary Beth F. Johnston, John H. Lawrence, Nora E. Becerra, & Laura A. Musselman, The False Claims Act and Health Care: 2020 Recoveries and 2021 Outlook, K&L Gates (Feb. 22, 2021), https://www.klgates.com/The- False-Claims-Act-and-Health-Care-2020-Recoveries-and-2021-Outlook-2-22-2021.

4 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act- settlements-and-judgments-exceed-56-billion-fiscal-year. Recoveries in FY 2021 were exceeded only by those in FY 2014, which saw US$6.2 billion in civil fraud recoveries. See Note 2, supra.

5 See U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download. Importantly, this sum reflects only federal recoveries; Medicaid recoveries are not accounted for in this figure. Id.

6 Id.

7 See id.

8 See id. Of the US$1.7 billion in recoveries in qui tam actions in FY 2021, US$1.2 billion (71%) resulted from matters in which the DOJ intervened or otherwise pursued. See id. For health care qui tam matters, US$1.5 billion was recovered, of which US$1 billion was attributable to cases in which the DOJ intervened/otherwise pursued. See id.

9 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Announces Global Resolution of Criminal and Civil Investigations with Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma and Civil Settlement with Members of the Sackler Family (Oct. 21, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-global-resolution-criminal-and-civil-investigations-opioid.

10 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Medicare Advantage Provider to Pay $6.3 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Nov. 16, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medicare-advantage-provider-pay-63-million-settle-false- claims-act-allegations.

11 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Northern Ohio Health System Agrees to Pay Over $21 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations for Improper Payments to Referring Physicians (July 2, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/northern-ohio-health-system-agrees-pay-over-21-million-resolve-false-claims-act- allegations; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Prime Healthcare Services and Two Doctors Agree to Pay $37.5 Million to Settle Allegations of Kickbacks, Billing for a Suspended Doctor, and False Claims for Implantable Medical Hardware (July 19, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/prime-healthcare-services-and-two-doctors-agree-pay-375-million-settle- allegations-kickbacks; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Sutter Health and Affiliates to Pay $90 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations of Mischarging the Medicare Advantage Program (Aug. 30, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/sutter-health-and-affiliates-pay-90-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-mischarging; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., United States Intervenes and Files Complaint in False Claims Act Suit Against Health Insurer for Submitting Unsupported Diagnoses to the Medicare Advantage Program (Sept. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-intervenes-and-files-complaint-false-claims-act-suit-against-health-insurer.

12 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Mail-Order Diabetic Testing Supplier and Parent Company Agree to Pay $160 Million to Resolve Alleged False Claims to Medicare (Aug. 2, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/mail-order-diabetic- testing-supplier-and-parent-company-agree-pay-160-million-resolve-alleged.

13 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., United States Obtains $140 Million in False Claims Act Judgments Against South Carolina Pain Management Clinics, Drug Testing Laboratories and a Substance Abuse Counseling Center (Sept. 3, 2021).

14 See, e.g., id.

15 See, e.g., id.

16 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Pharmaceutical Companies Pay Over $400 Million to Resolve Alleged False Claims Act Liability for Price-Fixing of Generic Drugs (Oct. 1, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/pharmaceutical- companies-pay-over-400-million-resolve-alleged-false-claims-act-liability.

17 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Ohio Treatment Facilities and Corporate Parent Agree to Pay $10.25 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations of Kickbacks to Patients and Unnecessary Admissions (March 5, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/ohio-treatment-facilities-and-corporate-parent-agree-pay-1025-million-resolve-false-claims.

18 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Home Health Agency Operator BAYADA to Pay $17 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations for Paying Kickback (Sept. 8, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/home-health-agency-operator- bayada-pay-17-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations-paying.

19 E.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Texas Heart Hospital and Wholly-Owned Subsidiary THHBP Management Company LLC to Pay $48 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Related to Alleged Kickbacks (Dec. 18, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/texas-heart-hospital-and-wholly-owned-subsidiary-thhbp-management-company-llc-pay-48- million.

20 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

21 Universal Health Servs., Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Escobar, 579 U.S. 176, 195 (2016) (“[I]f the Government pays a particular claim in full despite its actual knowledge that certain requirements were violated, that is very strong evidence that those requirements are not material”).

22 Compare U.S. ex rel. Borzilleri v. Bayer Healthcare Pharms. Inc., 24 F.4th 32 (1st Cir. Jan. 21, 2022) (government’s motion to dismiss will be granted unless the relator can establish “the government is transgressing constitutional limitations or perpetrating a fraud on the court”) with U.S. ex rel. CIMZNHCA, LLC v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835, 848 (7th Cir. 2020) (in order for the government to dismiss relator’s complaint after its automatic intervention rights have expired, it must first intervene by showing “good cause”), U.S. v. Everglades Coll., Inc., 855 F.3d 1279, 1285-86 (11th Cir. 2017) (the government may dismiss relator’s complaint at any point and need not intervene to do so), Swift v. U.S., 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (government has “unfettered right” to dismiss), and U.S. ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird-Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998) (government must articulate “valid government purpose” rationally related to dismissal).

23 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act-settlements-and- judgments-exceed-56-billion-fiscal-year.

24 See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims- act-cases-fiscal-year-2020.

25 Id.; U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

26 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download

27 Id.

28 Id.

29 Id.

30 See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims- act-cases-fiscal-year-2020.

31 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

32 Id.

33 Id.

34 Id.

35 Id.

36 Id.

37 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

38 Id.

39 Id.

40 Id.

41 Id.

42 Id.

43 Id.

44 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/file/1467871/download.

45 Id.

46 This program was previously known as the Medicare EHR Incentive Program.

47 The proposal would need to pass the Senate, the House of Representatives, and be signed into law by the President in order to become law.

48 False Claims Amendments Act of 2021, S. 2428, 117th Cong. (July 22, 2021).

49 Id.

50 False Claims Amendments Act of 2021, S. 2428, 117th Cong. (Nov. 16, 2021).

51 Id. at § 2 (emphasis added).

52 Universal Health Servs., Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Escobar, 579 U.S. 176, 195, 2003 (2016).

53 False Claims Amendments Act of 2021, S. 2428, 117th Cong. (Nov. 16, 2021).

54 Id. at § 3.

55 Escobar, 579 U.S. 176, 178 (2016).

56 Id. at 195.

57 See Press Release, U.S. Senate, Senators Introduce Bipartisan Legislation To Fight Government Waste, Fraud (July 26, 2021), https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/senators-introduce-of-bipartisan-legislation-to-fight- government-waste-fraud.

58 Id.

59 Id.

60 Id.

61 Id.

62 False Claims Amendments Act of 2021, S. 2428, 117th Cong. § 3 (July 22, 2021).

63 Id.

64 Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003).

65 United States ex rel. CIMZNHCA, LLC v. UCB, Inc., 970 F.3d 835, 849-50 (7th Cir. 2020).

66 U.S. ex rel., Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird-Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998).

67 See Memorandum from Michael D. Granston on Factors for Evaluating Dismissal Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 3730(c)(2)(A),

U.S. Dep’t of Just. (Jan. 10, 2018), https://nicholsliu.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Memo-for-Evaluating-Dismissal- Pursuant-to-31-U-S.pdf (hereinafter Granston Memo). This memorandum was authored by Michael Granston, Director of the Civil Fraud Section of the Commercial Litigation Branch.

68 Granston Memo at 7.

69 See Press Release, U.S. Senate, Grassley Questions Use of DOJ Memo To Limit Recovery of Tax Dollars Lost to Fraud (September 4, 2019), https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-questions-use-doj-memo- limit-recovery-tax-dollars-lost-fraud.

70 Id.

71 MJ Kim & Jessica Sharron, In the Aftermath of the Granston Memo, the DOJ Addresses (Some of) Grassley’s Concerns (February 13, 2020), https://www.alstongovcon.com/in-the-aftermath-of-the-granston-memo-the-doj-addresses-some-of- grassleys-concerns/.

72 Id.

73 See Letter from Senator Chuck Grassley to Merrick Garland, Attorney General Nominee (February 24, 2021), https://g7x5y3i9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-02-24-CEG-to-DOJAG-Nominee-Garland-regarding- FCA.pdf.

74 Id.

75 See Letter, Am. Hosp. Ass’n, AHA, Others, Express Opposition to the False Claims Amendments Act (S. 2428) (October 27, 2021), https://www.aha.org/lettercomment/2021-10-27-aha-others-express-opposition-false-claims- amendments-act-s-2428.

76 Id.

77 Id.

78 Id.

79 Id.

80 Id.

81 See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed

$5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act- settlements-and-judgments-exceed-56-billion-fiscal-year.

82 The HITECH Act is part of the larger American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, an economic stimulus plan designed, in part, to improve the nation’s health care delivery system by digitizing all patient records. See American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, 111th Congress (2009-10), www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/1.

83 See U.S. Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Promoting Interoperability Programs, (last visited Feb. 17, 2021), https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms.

84 The EHR Incentive Program was transitioned to become one of the four components of the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. See Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Meaningful Use, (last visited Feb. 17, 2021), https://www.healthit.gov/topic/meaningful-use-and- macra/meaningful-use.

85 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b. The AKS provides that “a claim that includes items or services resulting from a violation of this section constitutes a false or fraudulent claim for the purposes of [the FCA].” Id. at § 1320a-7b(g).

86 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims- act-cases-fiscal-year-2020. Moreover, in public remarks to the Federal Bar Association in 2020, the former head of DOJ’s Civil Division—the litigating component responsible for supervising FCA litigation and implementing FCA enforcement policies nationwide—stated that health care providers should anticipate ongoing scrutiny in relation to their use of and representations related to EHRs. David M. Maria & Trevor T. Garmey, DOJ Civil Division Highlights False Claims Act Priorities for 2020, The National Law Review, (March 30, 2020), https://www.natlawreview.com/article/doj-civil-division-highlights-false-claims-act-priorities-2020.

87 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Athenahealth Agrees to Pay $18.25 Million to Resolve Allegations that It Paid Illegal Kickbacks, (Jan. 28, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ma/pr/athenahealth-agrees-pay-1825-million-resolve-allegations- it-paid-illegal-kickbacks; see also Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Athena Settlement Agreement (last visited Mar 16, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ma/press-release/file/1361181/download.

88 Complaint in Intervention, U.S. ex el. Geordie Sanborn, Cheryl Lovell, and William McKusick v. AthenaHealth, Inc., No. 1:17-cv-12125-NMG, ECF No. 60 (D. Mass. Jan. 25, 2021).

89 Id. at ¶ 70.

90 See Criminal Information, U.S. v. Prac. Fusion, Inc., No. 2:20-cr-00011-WKS, ECF No. 1 (D. Vt. Jan. 27, 2020).

91 Id.; see also Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $145 Million to Resolve Criminal and Civil Investigations (Jan 27, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-145- million-resolve-criminal-and-civil-investigations-0.

92 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $145 Million to Resolve Criminal and Civil Investigations (Jan 27, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-145-million-resolve- criminal-and-civil-investigations-0.

93 Deferred Prosecution Agreement, U.S. v. Prac. Fusion, Inc., No. 2:20-cr-00011-WKS, ECF No. 2 (D. Vt. Jan. 27, 2020).

94 See Complaint, U.S. v. Greenway Health, LLC, No. 2:19-cv-00020-CR, ECF No. 1 (D. Vt. Feb. 06, 2019).

95 Id. at ¶¶ 3, 5, 83.

96 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $57.25 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations, (Feb. 6, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-5725-million-settle-false- claims-act-allegations.

97 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $155 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (May 31, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-155-million-settle-false- claims-act-allegations; see also Complaint in Intervention, U.S. v. eClinicalWorks, No. 2:15-cv-00095-wks, ECF No. 23 (D. Vt. May 1, 2015).

98 See id. at ¶ 44. More specifically, the government alleged that eClinicalWorks modified its software by “hardcoding” only the drug codes required for testing; it did not accurately record user actions in an audit log, and that it failed to satisfy data portability requirements intended to permit healthcare providers to exchange information between different EHR software. Id. ¶ 44.

99 Id.

100 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $155 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (May 31, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-155-million-settle-false- claims-act-allegations.

101 Press Release, Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $57.25 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Feb. 6, 2019) (“In 2019, the DOJ announced the resolution of two matters against EHR developers that represented “the two largest recoveries in the history of the District [of Vermont]” and that “EHR companies should consider themselves on notice.”).

102 Press Release, Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims-act- cases-fiscal-year-2020 (affirming that “complex EHR-related fraud schemes remain a focus of the [DOJ’s] work”).

103 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022) (reporting a US$18.25 million EHR-related FCA/AKS recovery).

104 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Athenahealth Agrees to Pay $18.25 Million to Resolve Allegations that It Paid Illegal Kickbacks (Jan. 28, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ma/pr/athenahealth-agrees-pay-1825-million-resolve- allegations-it-paid-illegal-kickbacks.

105 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $145 Million to Resolve Criminal and Civil Investigations (Jan 27, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-145-million-resolve- criminal-and-civil-investigations-0.

106 See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Former Shelby County Hospital CFO Sentenced in EHR Incentive Case (June 17, 2015), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edtx/pr/former-shelby-county-hospital-cfo-sentenced-ehr-incentive-case.

107 42 U.S.C. § 1395w-21. References in the statute to “Medicare+Choice,” the predecessor to MA, are “deemed a reference to . . . ‘MA.’” Id. at §1395w-21 note.

108 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act- settlements-and-judgments-exceed-56-billion-fiscal-year.

109 See Congressional Budget Office, Baseline Projections as of March 6, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020- 03/51302-2020-03-medicare.pdf.

110 42 U.S.C. §§ 1395w-21 to 1395w-28.

111 Id. at 1395w-23.

112 Id.

113 Id. at 1395w-23(a)(1)(C)(i); see also 42 C.F.R. § 422.308(e).

114 42 C.F.R. at § 422.504(l) (“Accurate risk-adjusted payments rely on the diagnosis coding derived from the member’s medical record.”).

115 Complaint in Intervention, No. 3:13-cv-03891-EMC, ECF No. 110 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 25, 2021).

116 Id. at ¶ 184.

117 Id. at ¶¶ 133-65. The Complaint alleges that the Health System’s “‘data mining’ programs focused on identifying

brand-new diagnoses, that is, diagnoses relating to conditions that no physician had ever diagnosed the patient as having

. . . using algorithms that mined the patient’s electronic medical records for key words, lab results, medications, clinical indicators, and other items that . . . might be suggestive of potential diagnoses that would increase risk-adjustment payments.” Id. at ¶ 133.

118 Id. at ¶¶ 166-83.

119 Id. at ¶ 170.

120 The practice of identifying only new diagnoses is known as a “one-way review.” This practice contrasts with “two-way reviews,” in which allegedly inappropriate diagnoses are removed from patient medical records at the same time appropriate diagnoses are added.

121 Complaint in Intervention, United States ex rel. Ross v. Independent Health Ass'n, No. 1:12-cv-00299-WMS, ECF No. 142 (W.D.N.Y. Sept. 13, 2021); see also Press Release, Dep’t of Just., United States Intervenes and Files Complaint in False Claims Act Suit Against Health Insurer for Submitting Unsupported Diagnoses to the Medicare Advantage Program (Sept. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-intervenes-and-files-complaint-false-claims-act-suit-against- health-insurer.

122 See Dep’t of Justice, Sutter Health and Affiliates to Pay $90 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations of Mischarging the Medicare Advantage Program (Aug. 30, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/sutter-health-and-affiliates- pay-90-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-mischarging.

123 See Dep’t of Justice, Medicare Advantage Provider to Pay $270 Million to Settle False Claims Act Liabilities (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medicare-advantage-provider-pay-270-million-settle-false-claims-act-liabilities. 124 Complaint, U.S. v. Anthem, Inc., No. 1:20-cv-02593-ALC, ECF No. 1 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2020); see also Dep’t of Justice, Manhattan U.S. Attorney Files Civil Fraud Suit Against Anthem, Inc., for Falsely Certifying the Accuracy Of Its

124 Diagnosis Data (Mar. 27, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-files-civil-fraud-suit-against- anthem-inc-falsely-certifying.

125 Complaint, U.S. v. Anthem, Inc., No. 1:20-cv-02593-ALC, ECF No. 1 at ¶¶ 8, 142.

126 Complaint in Intervention, U.S. ex rel. Ross v. Indep. Health Ass’n, No. 1:12-cv-00299-WMS at ¶¶ 296, 304, 313, 330, 338, ECF No. 142 (W.D.N.Y. Sept. 13, 2021).

127 Complaint in Intervention, U.S. ex rel. Poehling v. United HealthCare Servs., Inc., No. 2:16-cv-08697-FMO-SS, ECF No. 171 at ¶¶ 12-13, 164, 178-95 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 17, 2017).

128 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department’s False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act-settlements- and-judgments-exceed-56-billion-fiscal-year.

129 Azar v. Allina Health Servs., 139 S. Ct. 1804 (2019).

130 See, e.g., Polansky v. Exec. Health Res., Inc., 422 F.Supp.3d 916 (E.D. Pa. 2019).

131 See Mark A. Rush, Mary Beth F. Johnston, John H. Lawrence, Nora E. Becerra, & Laura A. Musselman, The False Claims Act and Health Care: 2020 Recoveries and 2021 Outlook, K&L Gates (Feb. 22, 2021), https://www.klgates.com/The-False-Claims-Act-and-Health-Care-2020-Recoveries-and-2021-Outlook-2-22-2021. (“FCA defendants may be able to argue forcefully that alleged non-compliance with a substantive legal standard that has not gone through the notice-and-comment process cannot form a basis for establishing falsity.”).

/>i

/>i