On May 17, 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) issued final regulations addressing how the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) each apply to employer-sponsored wellness plans. The primary focus of the EEOC's regulations is on what it means for a wellness program to be "voluntary." These regulations generally track and attempt to harmonize the EEOC's position regarding the ADA and GINA with other statutory and regulatory guidance regarding the operation of wellness plans under the Health Insurance Portability and Accessibility Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Nevertheless, they include certain important differences from the existing guidance under HIPAA and the ACA.

Certain portions of these final EEOC regulations (namely provisions relating to a notice requirement, the 30 percent limit on incentives for participation in a wellness plan, and the GINA rules that apply to spousal Health Risk Assessments (HRAs)) are effective for plan years beginning on and after January 1, 2017. However, the EEOC's position is that the remainder of these final regulations merely clarify and reinforce existing statutory obligations under the ADA and GINA, and apply both before and after May 17, 2016. Thus, these regulations require immediate attention.

Background

The ADA permits employers to conduct medical inquiries and examinations of employees if the inquiry or examination is (a) "job-related and consistent with business necessity" or (b) "voluntary" as part of an employee health program. 42 U.S.C. § 12112(d). The EEOC has long asserted that: "A wellness program is 'voluntary' as long as an employer neither requires participation nor penalizes employees who do not participate." EEOC Enforcement Guidance: Disability-Related Inquiries and Medical Examinations of Employees Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, Q&A-22 (2000).

In 2006, the U.S. Departments of Labor, Treasury, and Health and Human Services issued regulations governing the operation of wellness plans, and participant incentives linked to wellness plans, under HIPAA (the HIPAA Regulations). The HIPAA Regulations essentially divided wellness programs into two categories: (1) "participatory" wellness programs (e.g., completing an HRA) and (2) "health-contingent" wellness programs (e.g., walking programs, lowering cholesterol). The primary difference between these two types of programs is that participatory wellness programs do not require an individual to satisfy any goal relating to a health factor. For example, simply completing an HRA or attending a smoking cessation class is enough to receive the incentive under a participatory wellness program. By contrast, a health-contingent wellness program focuses on activities (walking) or the achievement of certain outcomes (lowering cholesterol), or at least attempting to do so. The HIPAA Regulations also permitted wellness plans to provide incentives relating to participation.

When the ACA was enacted in 2010, it essentially incorporated the existing HIPAA Regulations into its statutory language, and permitted an incentive relating to participation of 30 percent of the cost of employee-only coverage (generally described as 30 percent of the individual COBRA rate). The ACA also provided that the incentive for smoking cessation could be as high as 50 percent of the cost of employee-only coverage. In 2013, final regulations were issued expanding on the ACA's statutory provisions. Those regulations basically retained the permitted framework outlined in the HIPAA Regulations (the "HIPAA/ACA Regulations"). Thus, participatory wellness programs continued to be subject to minimal formal regulation, with the focus remaining on health-contingent wellness programs.

The EEOC in its final ADA and GINA regulations applies rules similar to the HIPAA/ACA Regulations to all employer-sponsored wellness plans that involve disability-related inquiries, regardless of whether the wellness program is a participatory program or a health-contingent program under the HIPAA/ACA Regulations.

EEOC's Final ADA Regulations

1. Definition of "Voluntary"

As noted above, the EEOC's final ADA regulations focus on what it means for a wellness program to be "voluntary." The regulations articulate the following factors necessary to demonstrate that the wellness program involving the use of HRAs or biometric screening is voluntary:

-

The employer cannot require employees to participate.

-

The employer cannot deny coverage under any of its group health plans (or particular benefit packages within those plans) or limit the extent of coverage (except for permitted incentives) to employees who do not participate.

-

The employer cannot take any adverse employment action against an employee who does not participate.

-

The employer must provide a notice to employees clearly explaining (i) what medical information will be obtained, (ii) who will receive the medical information, (iii) how the medical information will be used, (iv) the restrictions on the disclosure of the medical information and (v) the methods that will be applied to prevent improper disclosure of the medical information. A model notice will be posted on the EEOC website by mid-June 2016.

2. Thirty Percent Wellness Plan Participation Incentive

Under the final regulations, an employee is not "required to participate" in a wellness program if the total incentive available under all wellness programs (both participatory programs and health-contingent programs) does not exceed 30 percent of the cost of employee-only coverage (i.e., 30 percent of the individual COBRA rate). The concept of aggregation is an important difference between the EEOC's regulations and the existing HIPAA/ACA Regulations. Thus, according to the EEOC's regulations, if the annual cost of individual coverage is $5,000, and employees receive a $500 premium reduction for completing an HRA (a participatory wellness program), employees may only receive an additional $1,000 premium reduction for participating in a cholesterol-lowering program (a health-contingent wellness program).

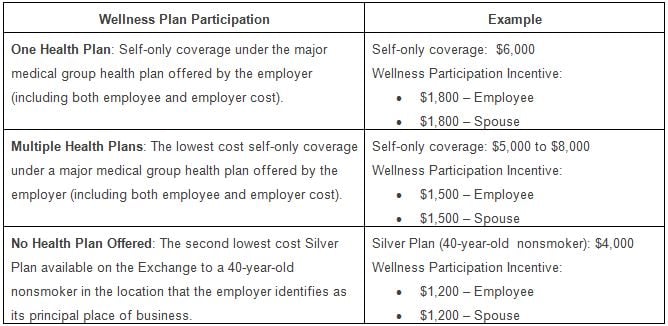

In addition to aggregation, the EEOC's regulations focus on the types of incentives involved, focusing primarily on whether an employer sponsors one, multiple or no medical plans.

It should be noted that under the final EEOC regulations, certain types of wellness programs are considered to not require disability-related inquiries or medical examinations to earn an incentive, and thus are outside of the EEOC's 30 percent aggregate incentive limitation. For example, employers can provide incentives to employees for attending such programs as nutrition, weight loss or smoking cessation classes (without any additional requirements) and not aggregate those incentives with other incentives applicable to other participatory and health-contingent wellness programs.

3. Fifty Percent Incentive for Smoking Cessation

As noted above, the HIPAA/ACA Regulations provide that a wellness program can offer an incentive of up to 50 percent of the cost of employee-only coverage (i.e., 50 percent of the individual COBRA rate) for participating in a tobacco-related wellness program. The EEOC’s regulations provide that a participatory wellness program that merely asks employees whether or not they use tobacco (or whether or not they ceased using tobacco upon completion of a smoking cessation program) can offer a 50 percent incentive as under the HIPAA/ACA Regulations. However, if tobacco-related incentives are tied to the results of a biometric screening or other medical examination that tests for the presence of nicotine or tobacco, that wellness program is subject to the EEOC’s 30 percent aggregate incentive limitation discussed above.

4. Effective Date

The portions of these final ADA regulations relating to a notice requirement and the 30 percent limit on incentives for participation in a wellness plan are effective for plan years beginning on and after January 1, 2017. However, the EEOC's position is that the remainder of these final regulations merely clarify and reinforce existing statutory obligations under the ADA, and apply both before and after the date the final regulations were issued.

EEOC's Final GINA Regulations

GINA generally restricts an employer's ability to acquire or disclose genetic information about its employees and also prohibits employers from using genetic information in making employment decisions. Genetic information includes information about family medical history (referred to in the regulations as "manifestation of disease or disorder").

1. Spousal Health Risk Assessments

The EEOC's final GINA regulations address the extent to which wellness plans may offer an incentive for a participant's spouse to provide medical history through a HRA or other means. Because the EEOC is concerned that medical history about an employee's children could form the basis of genetic discrimination against the employee, the regulations provide that employers may not seek such information about an employee's children (regardless of whether the children are adult or minor, biological or adopted). Rather, employers may only seek such information with respect to spouses.

In addition, an employer may not deny access to health insurance or any package of health insurance benefits to an employee and/or his or her family members, based on a spouse's refusal to provide information about his or her manifestation of disease or disorder to an employer-sponsored wellness program.

As with the EEOC's regulations under the ADA, the EEOC's GINA regulations apply to all employer-sponsored wellness programs that request genetic information, regardless of whether the program is part of, or outside of, an employer-sponsored group health plan.

As noted in the chart above, the maximum incentive for a spouse to provide information on an HRA about his or her medical history will be 30 percent of the total cost of employee self-only coverage, and the same concepts for calculating the value of the incentives if multiple plans exist or no plans exist apply to spousal incentives. Thus, the combined total incentive applicable to the employee and spouse will be no more than twice the cost of 30 percent of self-only coverage.

It should be noted, however, that an employer-sponsored wellness program does not request genetic information when it asks the spouse of an employee whether he or she uses tobacco or ceased using tobacco upon completion of a wellness program or when it requires a spouse to take a blood test to determine nicotine levels, as these are not requests for information about the spouse’s manifestation of disease or disorder.

2. Effective Date

The provisions relating to the level of incentive for spousal HRAs are effective with the plan year beginning on or after January 1, 2017. However, the EEOC's position is that the remainder of these final regulations merely clarify and reinforce existing statutory obligations under GINA, and apply both before and after the date the final regulations were issued.

/>i

/>i