The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) audits its member countries under the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, issuing recommendations for the faults OECD reviewers discover. Often, these faults consist of legal or political shortcomings in the enforcement of foreign bribery, but rarely legitimate concerns for the physical safety and well-being of parties involved in the foreign bribery prosecution process. Colombia, however, received a particular note in this troubling regard from the OECD in its Phase 3 audit report in 2019 and follow-up in 2021.

Death of a Whistleblower

Colombia’s foreign bribery detection, enforcement, and prosecution, while not the most egregious among OECD member countries, was discovered to be severely lacking by the reviewers. However, the chief concern among the reviewers was not the legal framework in Colombia, but rather the deaths of whistleblowers. “The lead examiners are seriously concerned about the absence of whistleblower protection and the circumstances faced by whistleblowers in Colombia,” the reviewers wrote. “Since Phase 2, media reports about the sudden deaths of a whistleblower who reported allegations of corruption related to the Odebrecht scandal and his son, as well as the suicide of a witness who was about to testify in an Odebrech- related investigation, suggest that the situation for whistleblowers and those who report corruption in Colombia is perceived as hostile.”

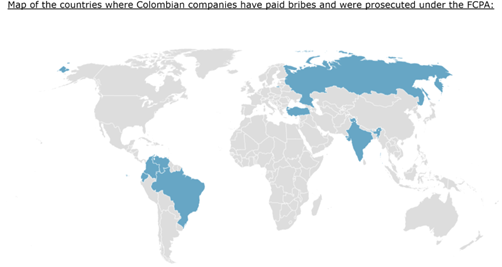

According to the report, three Colombians related to the investigation of Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction company, died or were killed. Between 2009 and 2014, Odebrecht had paid eleven bribes in Colombia over three separate projects, profiting fifty million dollars in Colombia alone. Odebrecht had paid bribes to foreign officials around the globe—twelve countries in total—making the Odebrecht case the “largest foreign bribery case in history,” according to the United States Department of Justice. Ultimately, Odebrecht was sanctioned $3.5 billion for its bribes in 2016.

In Colombia, Jorge Enrique Pizano, a whistleblower and key witness to the Odebrecht case, died suddenly of a heart attack. Just two days later, his son, Alejandro Pizano Ponce de Leon, died of cyanide poisoning after drinking from a water bottle laced with cyanide that had been on his father’s desk. “Jorge Enrique Pizano was negotiating his escape to the U.S. in exchange for documents related to the alleged corruption,” the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) wrote in an article cited by the OECD reviewers.

“These highly publicised cases of alleged retaliation against whistleblowers have had an additional deterrent effect on those who could potentially report allegations of corruption and foreign bribery,” the reviewers observed. Given these fears related to whistleblowing, and more importantly, the legitimate fear of death as exemplified by the Pizano tragedy, one would hope that Colombia would adopt whistleblower protection systems to ensure that whistleblowers can safely and effectively communicate their concerns. However, “Neither the Superintendency nor the PGO [Prosecutor General’s Office] have the mandate or capacity to protect those who report foreign bribery through their channel unless they receive the status of a witness.”

No Response to Critical Recommendations

Furthermore, Colombia has practically disregarded the OECD’s recommendations to this effect. In the Phase 3 follow-up report in 2021, the reviewers noted that none of the recommendations related to whistleblowers had been implemented. Of note was Recommendation 9: “In Phase 3, the Working Group expressed serious concerns about the absence of whistleblower protection and the circumstances faced by whistleblowers in the country. Bill 341/2020 initially included provisions on whistleblower protection, but regrettably, these were removed during the discussion of the bill in Parliament. This is Colombia’s third failed attempt since 2017 to legislate on whistleblower protection and reinforces the Working Group’s concerns from Phase 2 and Phase 3 regarding whistleblower protection in the country.”

Exonerating Fraudsters, Weak Prosecution, and Apathy

The other issues regarding Colombia’s foreign bribery prosecution capabilities appear minimal by comparison but are nonetheless important. The reviewers noted that Colombia has a high dependency on self-reports for detecting fraud, which, in and of itself, is not necessarily problematic. However, one of the “benefits for collaboration” that is offered to those who self-report foreign bribery is “the full or partial exoneration of the legal person.” Naturally, full exoneration significantly weakens the power (if not defeats the purpose) of prosecuting foreign bribery, a fact that the reviewers expressed concern about.

Furthermore, sanctions for foreign bribery offenses were far too low. Between Phases 2 and 3, Colombia successfully prosecuted a single foreign bribery case. The “Water Utility Company case,” as the reviewers refer to it, saw a Colombian company paying bribes to Ecuadorian officials in hopes of expediting a $14 million contract, and resulted in only $1.3 million in sanctions. The reviewers expressed disappointment that the initial sanction ($1.7 million) was “far below the maximum availability penalty,” and then further decreased to $1.3 million.

There has also been general disengagement with foreign bribery in Colombia. The Superintendency of Corporations effectively bears the burden of all foreign bribery-related actions in Colombia, including—to the reviewers’ concern and disappointment—training and awareness-raising. The reviewers “regret the serious decrease since Phase 2 in the engagement of a number of key government agencies, including the Secretariat of Transparency and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and query whether the responsibility for awareness-raising and training should rest so heavily on a law enforcement authority such as the Superintendency of Corporations,” the report stated. “The lead examiners are also disappointed by the low level of awareness displayed by a number of public officials and the judiciary at the on-site visit, especially when compared to similar levels at the time of Phase 2.”

The Need for FCPA Prosecution

While the Colombian prosecution appears to be lacking, the US has successfully secured almost $3.85 billion in sanctions through the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). The vast majority—over $3.6 billion—comes from the successful US prosecution of Odebrecht, as mentioned above, and its related cases. By contrast, at the time of the Phase 3 report, Colombian prosecution had only secured the $1.3 million in sanctions from the Water Utility Company case—around 0.03% of the sanctions collected by the United States.

While anticorruption in Colombia may not have the systemic failings of Türkiye’s framework or the extreme apathy of France’s approach that the OECD noted in the reports for those countries, Colombian anticorruption efforts nonetheless suffer. The death of a whistleblower and the killing of his son mark perhaps the most concerning aspect of any OECD member audit to date. Without proper protections, heightened awareness, and effective sanctions, anticorruption efforts in Colombia will simply falter in the dark.

/>i

/>i