The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) uncovered staggering inadequacies in anti-corruption efforts in The Netherlands’ 2024 Phase 4 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a comprehensive review of the country’s policies and procedures for countering corruption. The in-depth audit put to question any sense of legitimacy or strength in the Netherlands’s anti-corruption practices. The OECD reported being “concerned about the continued low level of foreign bribery enforcement in the Netherlands.”[1]

Standards for anti-corruption practices have been set by the United States which boasts strong whistleblower laws, like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and significant involvement in transnational corruption and bribery cases. With only 8 out of 25 recommendations fully implemented,[2] the Netherlands is not only failing to keep up with the OECD-recognized best practices, but has fallen short of even basic metrics.

According to the report, the Netherlands’ track record is cause for major concern. In 20 years, the country has sanctioned only three people of foreign bribery or related offenses and has concluded zero cases following criminal conviction at court.[3]

Structures in Shambles

One of the OECD’s chief concerns was a lack of clear structure or guidelines in the Netherlands’ anti-corruption efforts, specifically self-reporting for foreign bribery. The Netherlands responded to this plea for substantive policy with more platitudes, promising “consideration of a variety of aspects” when reviewing reports.[4]

Extradition is also affected by this disorganization. “To date, there is no database in the Netherlands to record information on the existence and status of extradition requests, by category of crime, including bribery.”[5] Similarly, prosecutors coordinate with the Tax and Customs Administration (TCA) agents only on a “case-by-case basis… without clear guidelines” which reportedly “result[s] in inconsistencies between non-trial resolutions and trial cases.”[6]

Anti-money laundering enforcement is also without clear guidelines in the Netherlands, where lead examiners “were concerned that guidance is lacking on what is expected of a company in terms of adequate procedures and an anti-bribery compliance program.”[7] Overall, there isn’t enough structure in place for successful anti-corruption enforcement.

The Netherlands themselves admit to a weak legal framework; in the current system Magistrates play a “central role,” but “have a limited capacity”[8] which causes delays. The OECD urged the Netherlands to reduce delays “caused by the inadequacy of the current processes;” the OECD considered this deficiency an emergent institutional issue. Ironically, the Netherlands report that addressing delays legislatively will be a slow process. But they attempt to assure that “the first step is still ongoing,” and that “at some point, relevant parties will be involved.”[9]

With these lackluster standards, it’s not surprising that the Netherlands is fumbling. Currently, only 2 cases are in prosecution; and one of those cases was dismissed because of the “inadmissibility of the proceedings.”[10] The Netherlands have even let slip cases that other countries were able to catch. The Netherlands discontinued 5 foreign bribery cases without issuing any sanctions.[11] The United States has stepped up to bat as the Netherlands have cowered from the plate, prosecuting 44 Dutch foreign bribery cases and collecting over $6.3 billion.[12]

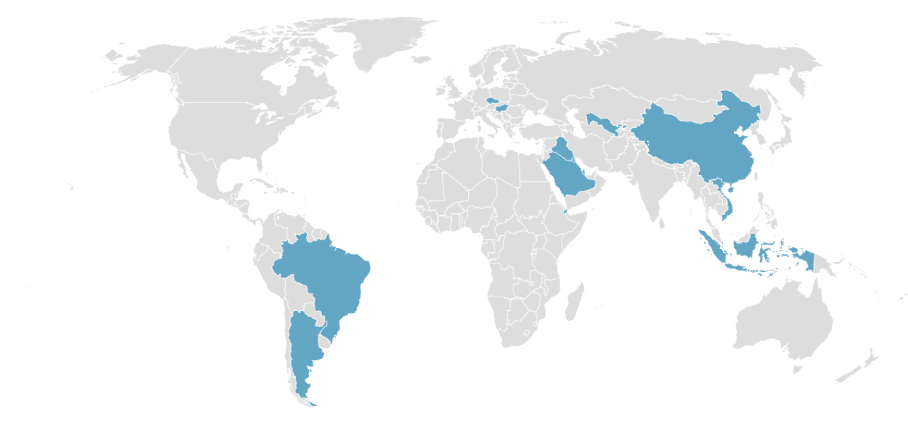

Map of countries Dutch Companies have allegedly bribed

In fact, almost all successful anti-corruption prosecutions of the Netherlands companies have been brought to justice by the United States under its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA); in three major cases alone Dutch companies had to pay over $4.6 billion to the US

Apathy Abounds

Despite the OECD’s recommendations, the Netherlands see no need for change. When the OECD recommended stronger sanctions, the Netherlands responded that they “do not intend to implement the recommendation, as the overall framework for sanctions currently in place is sufficient.”[13] This “sufficient” system only imposed sanctions on 1 natural person in a foreign bribery case using a Dutch law (article 74 of the Dutch Criminal Code) that is extremely weak and only applies to natural persons in “exceptional circumstances.”[14]

When the OECD recommended stronger penalties, the Netherlands stated “In the opinion of the Netherlands, such an increase is not necessary and not suitable within the further Dutch framework for penalties.”[15] This opinion of the Netherlands is directly at odds with the OECD lead examiners who were “concerned” about the penalties and thought “they were too low to be effective, proportionate and dissuasive in practice.”[16]

Even purposeful change is minimal. The Netherlands has a draft bill designed to tackle some of these anti-corruption issues, yet the country reports that “At this moment… the current goal of instituting criminal proceedings against natural persons, where possible, will not be altered by the draft bill.”[17]

In a similar case, the lead examiners mentioned that the 2015 Dutch amendments to the foreign bribery offence (Article 177 Dutch Code of Criminal Procedure), were not novel solutions and instead “largely conform[ed]” to the requirements of past legislation (Article 1 of the Convention). Therefore, these amendments “did not fully address issues identified in previous evaluations” as they were intended to.

The Netherlands have also failed to increase the maximum fines[18] and to improve legislation for non-trial resolutions.[19]

Windswept Whistleblowers

Whistleblowers, the most valuable anti-corruption resource available, are also victims of the Netherland’s insufficient practices. The OECD recommended that the Netherlands “transpose the Whistleblower Protection Directive, as a priority.”[20] The Whistleblower Protection Directive is a piece of legislation that essentially outlines whistleblowing procedures for internal reporting, requirements for reporting channels, protective measures for discrimination, and the framework for the House of Whistleblowers, a “research and advisory department.” The Dutch government reports letters of amendment and proposals, but as of the most recent report, whistleblower protection – an essential element of anti-corruption – “has not been adopted.”[21]

Furthermore, there are still no available guidelines for the country that “explain the extent to which self-reporting will be considered in resolving and sanctioning foreign bribery cases.”[22] For the reporters themselves, there is also a lack of clarity for self-reporting procedures. As these reporting problems prevail, “reforms concerning whistleblower protection and non-trial resolutions are currently still pending.”[23]

Although the Netherlands seem to be moving in a positive direction with pending legislation, there is a noted lack of enthusiasm in these efforts. The EU Whistleblower Protection Directive provision was described as an “optional provision.”[24] And, the Netherlands has only promised to “consider,” “evaluate,” and “examine” “wishes” and “proposals” without any necessary concrete steps towards change.[25]

No Reform

These displays of disorganization, apathy, and delays compelled the OECD to mark the “inadequacy of current processes” in the Netherlands.[26]

U.S. whistleblower attorney Stephen M. Kohn, who specializes in transnational corruption cases, echoed the frustration:

“The Netherlands has dropped the ball. Their failure to prosecute bribery and money laundering cases fuels poverty, authoritarianism, and corruption in developing countries. The Dutch government has turned its back on whistleblowers and human rights defenders worldwide.”

Despite this dire state, the Netherland’s anti-corruption practices can be revived by more faithfully following the OECD’s recommendations. With necessary changes to legal frameworks and resources, corruption will decrease and less Dutch money will be lost to outside sanctions and prosecutions.

/>i

/>i