This week, two federal appellate courts published notable opinions on the intersection between personal jurisdiction jurisprudence and Rule 23 class action procedure. The defendants in both cases face nationwide class actions, and each argued that the Supreme Court’s 2017 decision in Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California, 137 S. Ct. 1773, precludes district courts from exercising specific jurisdiction over the claims of unnamed putative class members from other states. The majority of a D.C. Circuit panel decided to resolve the appeal before it on alternate grounds. But in dissent, Judge Silberman explained why he understands Bristol-Myers’s holding to extend to nationwide class actions brought in federal court. The next day, a unanimous Seventh Circuit panel refused to extend Bristol-Myers to federal class actions.

As detailed here, the Supreme Court’s Bristol-Myers decision addresses state courts’ jurisdiction over the claims of non-resident plaintiffs in mass tort actions. The Court held that a California state court lacked jurisdiction over the defendant with respect to nonresident plaintiffs’ claims because the defendant was not incorporated in California and did not have its principal place of business in California (thus defeating general jurisdiction) and because the claims lacked an “adequate link” to California (thus defeating specific jurisdiction). Following that ruling, district courts across the country have split on whether to extend the logic of Bristol-Myers from state mass tort actions to nationwide class actions.

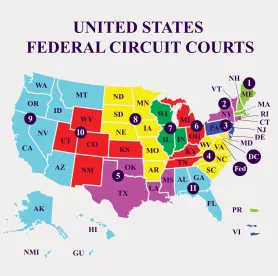

On Tuesday, the D.C. Circuit declined an opportunity to squarely confront this issue in Molock v. Whole Foods Market Group, Inc. The D.C. Circuit, on an interlocutory appeal, affirmed the district court’s denial of the defendant’s motion to dismiss the claims of all nonresident putative class members. Reasoning that putative class members are not “parties” to a lawsuit before a class is certified, Judge Tatel ruled that the defendant’s motion to dismiss their claims was premature. The opinion therefore did not reach the parties’ arguments about Bristol-Myers’s application to federal class actions. One member of the three-judge panel, Judge Silberman, dissented and explained his belief that the logic of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Bristol-Myers necessarily extended to the context of federal class actions.

The Seventh Circuit issued its opinion in Mussat v. IQVIA the very next day, reversing the district court’s grant of a motion to strike nationwide class allegations. Chief Judge Wood acknowledged in her opinion for the unanimous panel that, before the Bristol-Myers decision, the propriety of federal courts exercising specific jurisdiction over nationwide classes had “not been examined closely.” Analogizing to Supreme Court decisions disregarding unnamed class members for purposes of subject-matter jurisdiction and venue, the Seventh Circuit rejected the defendant’s request to apply Bristol-Myers’s logic to the class allegations before it: “[W]e hold that the principles announced in Bristol-Myers do not apply to the case of a nationwide class action filed in federal court under a federal statute.” One distinction between the two cases relates to the basis for subject matter jurisdiction: Molock involved state law claims brought under diversity jurisdiction, while Mussat relied on federal question jurisdiction.

Litigants should expect the issue of Bristol-Myers’s application to nationwide class actions to continue to percolate up to other appellate courts and potentially make its way before the Supreme Court. Personal jurisdiction aficionados may also be interested in Ford Motor Co. v. Bandemer, where the Supreme Court recently granted certiorari to address whether a plaintiff’s substantive claims must arise out of a defendant’s forum contacts in order to generate specific jurisdiction over the defendant.

/>i

/>i