Over the past year, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Japanese Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) have made concerted efforts to coordinate and join forces in the enforcement of U.S. and Japanese antitrust policies. This growing relationship makes sense, from the agencies’ perspective, given that they are both responsible for upholding their respective antitrust laws and prosecuting violators. The relationship really makes sense when one considers that the DOJ Antitrust Division’s prosecution of Japanese auto parts manufacturers has resulted in over $2.4 billion in criminal fines from their ongoing investigation of price fixing and bid rigging in the auto parts industry. On the surface, the JFTC’s teeth don’t seem as sharp as the DOJ’s, especially in light of the JFTC’s much heralded Leniency Program. But given the increasingly cozy relationship between the two enforcement agencies, corporate attorneys who suspect antitrust violations should be wary about advising their Japanese clients to race to the doors of the JFTC with a leniency application in hand.

The JFTC and the DOJ have developed a close partnership as a result of the ongoing investigation of Japanese auto parts manufacturers. The agencies have cooperated on merger and civil non-merger matters and gone so far as to draft a joint model waiver of confidentiality for individuals and companies to use in matters involving concurrent review by the DOJ and the JFTC. The model waiver allows for greater and more efficient communication between the two agencies when they are concurrently investigating a matter. The DOJ and JFTC have also instituted an exchange program for their employees. It is likely that the DOJ and JFTC will pursue additional coordination initiatives in the near future.

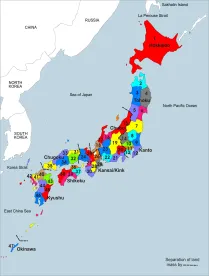

The JFTC, also known as Kotori, is tasked with enforcing the country’s Antimonopoly Act. The Antimonopoly Act (AMA) was enacted in 1947 as part of the Japanese government’s efforts to promote fair and free market competition in the country’s post-WWII era. The AMA prohibits three types of anticompetitive conduct: private monopolization, unreasonable restraints of trade, and unfair methods of competition. The enactment of the AMA led to the formation of the JFTC.

In April 2005, the JFTC introduced its Leniency Program which affords cooperating companies leniency for coming forward with violations of the AMA. The JFTC’s leniency formula is simple and straightforward. The first amnesty applicant to submit a leniency application for a specified product or service can apply for a 100 percent reduction in surcharge and total immunity. The second in line can apply for a 50 percent reduction in surcharge. The third, fourth, and fifth amnesty applicants are permitted to apply for a 30 percent reduction in surcharge. In most cases, the applications are confidential. For obvious reasons, the Leniency Program is popular and often used despite the fact that applicants are required to admit liability. The DOJ’s Leniency Program, on the other hand, is not as “lenient” as the JFTC’s. Although it offers the potential of avoiding conviction, criminal fines, and/or prison sentences, amnesty applicants rarely come out completely unscathed, especially given the inevitable civil litigation to follow. Furthermore, the only true beneficiary is the first whistleblower in line.

Although the JFTC’s Leniency Program is popular, there are some very real risks when dealing with the JFTC. First, there are due process issues – as “due process” as we know it in the United States does not exist with respect to the JFTC. The JFTC does not allow witnesses to have an attorney present during interviews, and the agency typically requires witnesses to sign pre-prepared written statements without receiving advice from an attorney. Second, the JFTC does not recognize attorney-client privilege, which means it can seize and review communications between an individual or company and their attorneys.

Given the incentive created by the JFTC Leniency Program, corporate counselors who become aware of potential violations of the AMA may be compelled to apply for leniency, especially if no one has yet submitted an application. But the ever increasing cooperation between the DOJ and the JFTC may pose some risks to an applicant. Consider the following scenario. A Japanese-based parent company with U.S.-based subsidiaries discovers it has violated the AMA, and likely violated U.S. antitrust laws in the process. The parent’s corporate counsel submits an application to the JFTC, essentially admitting to violations of the AMA and U.S. antitrust laws. Although the JFTC has confidentiality protections in place, it seems plausible, given the agencies’ close relationship, that the DOJ could receive some form of notice of the parent company’s violation of the AMA. Such notice would be a Pandora’s Box for a U.S.-based subsidiary, which would in turn put the parent at risk of U.S. criminal prosecution.

In sum, Japanese-based companies that have subsidiaries in the U.S. should be very considerate of the risks of taking advantage of the JFTC’s Leniency Program. A conscientious corporate counselor may actually put her company in greater risk of criminal prosecution by benefitting from the JFTC’s surcharge reduction and immunity.

/>i

/>i