Because of the unanticipated success of the Commodity Exchange Act’s (“CEA”) whistleblower law, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC” or “Commission”) faces a unique problem. The Commission cannot compensate whistleblowers, as required under law, because of a cap on the amount of money that can be deposited into a special fund used to pay rewards and other essential expenses necessary to operate the CFTC’s whistleblower office. The CTFC’s Consumer Protection Fund (“Fund”) is the exclusive Fund used to compensate whistleblowers who provide original information that results in a successful prosecution. All of the money deposited into the Fund comes directly from sanctions paid by fraudsters. However, because of the limit placed on the amount allowed to be deposited into the account, whistleblowers who disclose large frauds currently cannot be properly paid.

When Congress passed the CEA whistleblower law, it did not anticipate the program would have such a tremendous level of success. Since the Dodd-Frank Act was passed, whistleblowers have provided essential evidence permitting the CFTC to obtain billions in sanctions from fraudsters. However, the CFTC can only add a small fraction of the billions in sanctions recovered by whistleblower-triggered cases to the Fund because of the statutory cap. The success of the program, combined with the requirement to pay rewards, has resulted in a depletion of the Fund. Consequently, the CFTC has informed Members of the U.S. Senate that it is postponing the issuance of rewards.

The CFTC is caught between a rock and a hard place. Congress mandates that rewards be paid, but the Fund does not have the money to permit the CFTC to comply with the law. Despite the requirement to compensate them, whistleblowers, many of whom have lost their jobs and careers, now face prolonged economic hardship. The CFTC whistleblower program is in crisis.

This crisis was unintended and unforeseen. Congress established the CFTC Fund as part of the Dodd-Frank Act reforms enacted in 2010. At the time, the CFTC had no whistleblower program, and whistleblowers within the commodity markets were unknown. Thus, the $100 million limit placed on deposits into the Fund appeared very reasonable. Initially, this cap created no issues. For example, eighteen months after Congress passed the commodities whistleblower law, only 58 individuals filed complaints with the CFTC. This number of complaints compares to the over 3000 complaints filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) during the same period. Moreover, the CFTC did not pay its first whistleblower reward until May 19, 2014, nearly four years after the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law. That first award, which totaled $240,000, did not threaten the integrity of the Fund.

However, the CFTC whistleblower program has seen phenomenal growth. The CFTC has paid over $120 million in additional awards to qualified whistleblowers since paying the initial award in 2014. In FY 2020, over 1000 whistleblowers filed formal complaints with the CFTC documenting allegations of widespread frauds within the commodities markets. These 1000 complaints dwarfed the 58 claims filed in the first full year of the CTFC program.

By the end of fiscal year 2020, the CFTC’s enforcement program had come of age. As explained in the Commission’s Annual Report: the CFTC “filed more enforcement actions (113) than any other year in the agency’s history, imposing over a billion dollars of total monetary relief . . . [including returning over] $180 million defrauded from elderly victims.” The successful prosecutions have also resulted in enormous amounts of sanctions. Over the past three years, the Commission has issued $3.5 billion sanctions against fraudsters.

The growth in the CFTC’s program, based on the statistics published annually by the CFTC’s Office of the Whistleblower, is demonstrated in two charts. Chart 1 tracks the number of rewards paid to whistleblowers since the program was established. This chart clearly indicates that reward payments have increased over time and that the financial stress placed on the Fund is also growing.

Chart 1

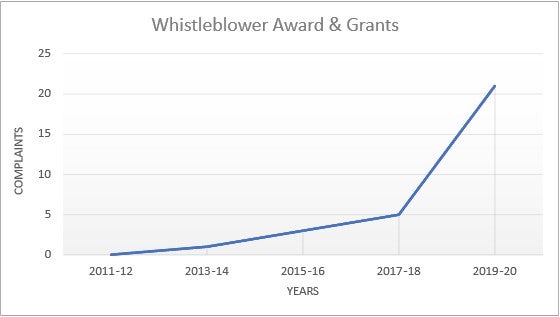

Chart 2 demonstrates the radical increase in the number of whistleblower complaints filed with the CFTC. These complaints are the backbone of the program. They contain the information needed to effectively police commodity frauds. Paradoxically, without increasing the size of the Fund, the more money obtained from whistleblower-triggered investigations, the less money is available, on a case-by-case basis, to pay the pending and future rewards.

Chart 2

Despite the growth of the whistleblower program and the billions collected in sanctions, the limit placed on the amount that the Commission can deposit into the Fund has remained unchanged since the Dodd-Frank Act was passed. Funding levels that seemed reasonable in 2010 are not reasonable today. The current cap on deposits into the Fund threatens the integrity of a highly effective enforcement program. Only by amending the CEA whistleblower law can the cap that restricts the pool of money available to compensate whistleblowers be increased. Without such an increase, the very whistleblowers the CEA was designed to incentivize and protect will be severely harmed.

In hindsight, the growth in commodities whistleblowing is not surprising. Similar qui tam laws designed to incentivize whistleblowers to report tax evasion, fraud in government contracting, and securities fraud have also been highly successful. Moreover, the size of the markets regulated by the CFTC is astronomical. At the time the Dodd-Frank Act became law, then-CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler explained the massive scope of the Commission’s new authorities: “The law gave the Commodity Futures Trading Commission oversight of the $300 trillion swaps market. . . At such size and complexity, it is essential that these markets work for the benefit of the American public; that they are transparent, open and competitive.” As further explained in the 2020 Annual Report of the CFTC, “The U.S. derivatives markets are the most vibrant, developed, and influential in the world.” These markets impact the prices of “countless goods and services” and are “vital to the real economy.”

The types of frauds that corrupt the commodities markets are also vast and complex. They include “spoofing,” swaps, fraud in the derivative, futures and options trading, foreign corruption, false reporting, market manipulation, insider trading, money laundering, forex trading, benchmark manipulation, and frauds associated with foreign currency exchanges and cryptocurrencies. Because of the hard-cap placed on the Fund to compensate whistleblowers, the growth in the CFTC program has not increased in the amount of money available to pay whistleblowers.

In an extremely troubling development, the CFTC has started delaying the processing of whistleblower cases due to a lack of funds. These delays will only intensify if the funding problem is not immediately addressed. Whistleblowers will personally suffer, many being denied the timely compensation they need to recover from being fired, blacklisted, or having their careers ruined. The major hardships, both economic and emotional, suffered by whistleblowers are undisputed and fully documented by a special study published by the New England Journal of Medicine.

The CFTC supports increasing the cap. This support is consistent with the whistleblower program’s success and numerous public statements issued by top Commission officials praising whistleblowers. For example, on July 27, 2020, the CTFC Director of Enforcement explained the importance of paying rewards in a timely manner based on the risk and sacrifices that whistleblowers face: “We recognize that often whistleblowers come forward to report misconduct at great personal and professional risk.” The Director further explained that the numerous successful whistleblower cases “serve as a reminder that the Whistleblower Program can reward that courage in a very real way, helping to soften the blow of any adverse consequences those whistleblowers might face.” The than-Chairman of the SEC expressed similar sentiments: “The Whistleblower Program has become an integral component in the agency’s enforcement arsenal . . . We hope that an award of this magnitude will incentivize whistleblowers to come forward with valuable information and provide notice to market participants that individuals are reporting quality information about violations of the Commodity Exchange Act [CEA].”

A bipartisan group of Senators, including Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Maggie Hassan (D-NH), Joni Ernst (R-IA), and Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), recognizing the crisis faced by the CFTC Whistleblower Program, proposed legislation to ensure that the program can continue to pay whistleblowers. The CFTC Fund Management Act, introduced on February 24, 2021, increases the cap on the amount of money that can be deposited into the Fund. This is an emergency fix designed to ensure that funds are available to compensate whistleblowers and continue the operations of the CFTC Whistleblower Office. This increase in the cap will not cost taxpayers any money, as all monies deposited into the Fund must come directly from sanctions obtained from successful enforcement actions. This increase simply reflects the significant increase in monetary sanctions obtained by the U.S. government from whistleblower-triggered cases and the resulting obligation to pay those whistleblowers a percentage of those sanctions.

The Senate bill is now pending before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry. In order to ensure that whistleblowers are paid in a timely manner, as mandated under the Dodd-Frank Act, the Chairwomen of the Committee, Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), along with Senator John Boozman (R-AR), the committee’s Ranking Member, are needed to support the bill’s sponsors in their effort to have the CFTC Fund Management Act quickly approved to stop the current financial crisis facing the CFTC.

/>i

/>i