Starting a business in the United States can be difficult for a foreign national. While a business establishment may be simple, U.S. work authorization may be more difficult to attain. The L-1 Intracompany Transfer visa can provide a path towards long-term work authorization in the United States for founders and employees of a U.S. company.

Overview of the L-1

First authorized[1] in 1970, an L-1 Intracompany Transfer petition allows multinational organizations to transfer managers, executives, and employees with “specialized knowledge”[2] from a foreign entity to a commonly owned and controlled U.S.-based parent company, subsidiary, affiliate, branch, or joint venture. Critically, the transferring employee must have worked for the company abroad for at least one continuous year within the last three years. Any time spent in the United States would delay completion of the continuous year.

Image 1: A graphical representation of the standard L-1 process.

Under the standard L-1 model, the initial grant of L-1 status will be for up to three years. Employees coming to work in the United States as executives or managers receive L-1A status, which can be extended beyond the three-year initial grant of status, in two-year increments, for up to seven years. Employees coming to work in the United States in a specialized knowledge capacity receive L-1B status, which can be extended beyond the three-year initial grant of status, in two-year increments, for up to five years.

Importantly, L-1 closely relates to the EB-1C “Multinational Manager” immigrant visa.[3] So long as the foreign national has worked as an executive or manager abroad, continues to work as a manager or executive in the U.S., and the U.S. entity has been doing business for one year, the employee would be eligible to file for permanent residence in the EB-1 preference category. EB-1 rarely faces long backlogs. This means that by leaving the U.S. for a year to be a manager or executive, you may have access to a faster permanent residence process.

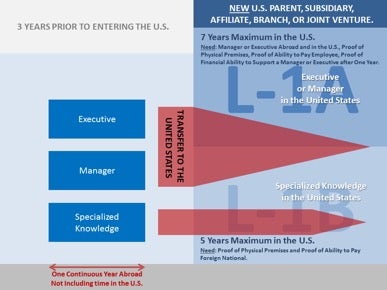

Use of the L-1 with New Businesses

While the most obvious petitioners for L-1 status would be large, established, multinational companies, the regulations also provide a means to transfer key employees who will either start operations in the U.S. or join operations that have existed for less than one year. This is known as the “New Office L.”[4]

Image 2: A graphical representation of the New Office L-1 process.

The New Office L requires additional documentation, as compared to a standard L-1 petition, including:

-

Proof of sufficient physical premises in the U.S.

-

Proof of ability to pay the foreign national.

Additionally, if seeking an L-1A, there are further documentary requirements, including:

-

Proof of work as an executive or manager abroad. (Specialized knowledge employees cannot receive L-1A visa status to work for an entity that has existed for less than a year).

-

Proof of ability to support a manager or executive after one year, including:

-

The scope of the entity.

-

The organizational structure of the domestic and foreign entity.

-

The financial goals of the domestic entity.

-

The size of the investment in the domestic entity.

-

Proof of the foreign entity’s financial ability to start work in the United States.

-

If approved, the New Office L beneficiary will initially receive one year of status. As with the standard L-1, executives and managers receive L-1A status, which could be extended, in two-year terms, for up to seven years. Specialized knowledge employees would receive L-1B status, which could be extended, in two-year terms, for up to five years. Employees who were managers and executives abroad and in the United States would still be eligible to file for permanent residence via EB-1C after one year of U.S.-based operations.

As such, the New Office L can be a great option for those looking to start businesses in the United States who can arrange affiliated work abroad for one year.

Tips for Filing the New Office L

While the items above may seem straightforward, it is not uncommon for even extensively documented petitions to receive requests for additional evidence from USCIS. The following filing tips will help improve your chances of success:

-

Detail the qualifying relationship. With newer entities, USCIS tends to request extensive substantiation of an equity relationship between the company abroad and the employer in the United States. Be sure to prepare clear documentation, such as stock certificates, stock ledgers, or membership agreements showing common ownership. You may even want to provide minutes of Board of Directors meetings that verify the corporate ownership, or an affidavit that certifies the accuracy of the documents.

-

Register with Dun & Bradstreet. USCIS verifies petitions against its Validation Instrument for Business Enterprises (“VIBE”) database. The VIBE database draws its information from the records of Dun & Bradstreet, a private corporate credit monitoring company. Because the domestic employer will, by definition, be new, it is unlikely that Dun & Bradstreet will have accurate information. Non-verification in the VIBE system can lead to additional information requests, as well as increased general skepticism of the petition, from USCIS. By registering for a “DUNS” number, you will be able to ensure that Dun & Bradstreet (and, by extension, VIBE) has accurate information concerning your company, preventing the VIBE-induced negative consequences with USCIS described above. You may register for a DUNS number here: https://www.dandb.com/product/companyupdate/companyupdateLogin?execution=e1s1

-

Draft a business plan. As noted above, the New Office L requires extensive financial documentation, particularly when bringing over a manager or executive. To address this, prepare a detailed business plan. Depending on your experience with business plans, you may want to hire a professional business plan writer. The business plan should include details about the proposed industry of the new entity, details about the decision to expand into the United States, information about the employee, financial projections and goals, anticipated payroll, an anticipated personnel chart after 12 months of operations, and job descriptions for all anticipated employees on the organizational chart with the anticipated percentages of time spent on each job duty.

-

Document your United States physical office. The New Office L requires proof of your physical office in the United States. This should include a fully executed lease or deed. Make sure that these documents are signed and dated by all relevant parties. You may also want to include proof of any payments made for the lease or property, as well as pictures of the facility. If you include pictures, make sure that your company’s logo is displayed on the premises. Also note that shared spaces are disfavored by USCIS. USCIS wants to see that you have unrestricted access to your workspace.

-

Anticipate a difficult extension process. The extension process for the New Office L petition can be just as difficult as the initial submission. Be sure to meet the approved staffing goals. You should also gather documentation of the employee’s work in the relevant capacity:

-

For executives, this would include policies that have been created and implemented, as well as proof of senior-level decisions or signing authority.

-

For managers, this would include proof of managing employees (such as hiring records or annual reviews of subordinates), proof of senior-level decisions or budgets, and payroll verifying the existence of subordinate employees.

-

For specialized knowledge employees, this would include proof of company-specific work, such as work with company-specific products, software, processes, or infrastructure, as well as any documentation of unique expertise with the same.

-

Conclusion

If an individual is able to work as a manager, executive, or specialized knowledge employee for a year outside the U.S., the New Office L provides a direct path to starting a company in the United States. While you may still receive government pushback, following the preceding steps should allow you to avoid common pitfalls.

[1] See Public Law 91-225: http://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/91/225.pdf.

[2] The latest guidance on what constitutes specialized knowledge is found here: https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Laws/Memoranda/2015/L-1B_Memorandum_8_14_15_draft_for_FINAL_4pmAPPROVED.pdf.

[3] See 8 C.F.R. §204.5(j).

[4] See 8 C.F.R. §214.2(l)(3)(v)-(vi).

/>i

/>i