Imagine excitedly filing a patent application, waiting years for the case to be examined, and then finding your application rejected on grounds that it is obvious or anticipated by your own previously published work. This is a common situation, but it may be avoided with careful planning.

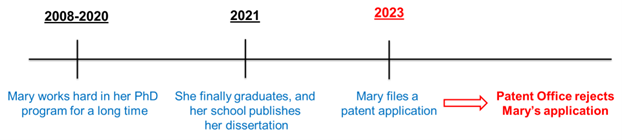

Generally, in the U.S., your own publications are considered prior art to new patent applications if they have been published for more than a year when you file a new patent application. Consider the example below. Mary’s own work is cited against her patent application because her dissertation included the same idea 2 years before. Note, the examples here are simplified, and there may be additional complications with multiple inventors and authors.

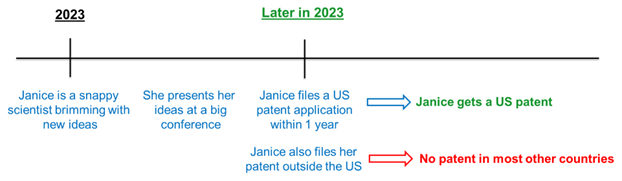

On the other hand, the U.S. (along with some other countries) has a 1-year grace period, so the publication is not considered by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office when the application was filed within the year following publication. The grace period does not apply in most other countries (e.g., Europe and China), so in the additional situation below, Janice will have to be happy with obtaining the patent on her new concepts only in the U.S.:

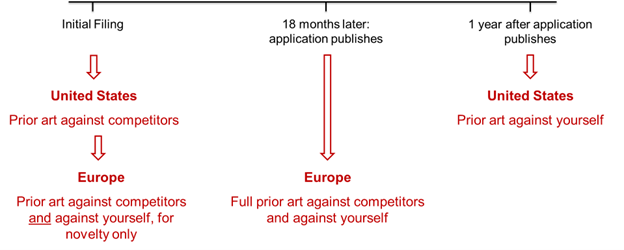

Patent applications generally are published about 18 months after they are initially filed. Some similar concepts as for non-patent publications apply when a patent application publishes in that you still have a year from publication for it to be considered prior art against your own subsequent patent filings in the U.S. So, for example, you have until 2 ½ years after filing your first application for it to be considered prior art against your own second application in the U.S. A difference is that for subsequent applications filed by competitors, your application will be prior art to their work on the day your application was filed.

To summarize the rules in the U.S., your own publication is prior art to your own new patent applications 1 year after the publication date, although other people such as competitors will have to deal with your publication as prior art against their new patent applications the day it is published.

The rules are different outside the U.S. When considering prior art in Europe, there is no distinction when the subsequent application is filed by you compared to when it is filed by a competitor. There is a distinction, though, for whether the second application is filed before publication of the first application or after it. In Europe, if a second filing is made before publication of the first application, a new aspect in the second application may be patented as long as it is novel relative to the first application. If the second application is filed after the first application publishes, the second application must also include an “inventive step,” which is similar to being considered nonobvious, to be patented:

You can use these rules to your advantage as you develop your patent strategy, and as your inventions progress. A common patent filing strategy is to include any improvements you make relative to inventions from your first application in a second patent filing right before the first application publishes. This gives you the ability to avoid having the first application counted against your second filing in the U.S., and also increases the chances of the same in Europe because if you really make improvements in the second application they are likely to be novel compared to the first application. This also has the advantage of extending your patent term by 18 months, an aspect that may be valuable in certain industries, particularly when the first and the second patents both cover aspects in a marketed product.

Overall, with careful planning, you can maximize your chances of getting a patent allowed if you avoid publishing or publicly presenting on concepts that you will later patent. You may also be able to get further patents on even minor improvements by timing your patent filing strategy to include new filings at certain intervals, and this can help maximize your patent term.

/>i

/>i