New technology will undoubtedly improve lives, but it comes with new risks.

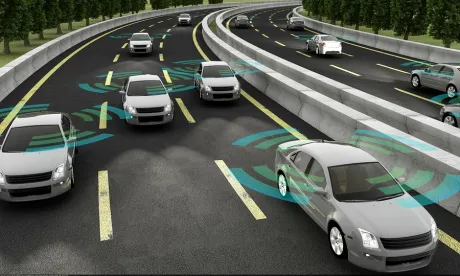

Researchers estimate autonomous vehicles (AVs) could reduce accident rates by up to 90 percent, which would save more than 30,000 lives each year and avoid millions of injuries on American roads. Technology can mitigate many of our human weaknesses. According the General Motors Chairman Bob Lutz, “The autonomous car doesn’t drink, doesn’t do drugs, doesn’t text while driving and doesn’t get road rage. Autonomous cars don’t race other autonomous cars and they don’t go to sleep.” Though people may eventually be safer in autonomous cars than in traditional vehicles, we have a long way to go and a short time to get there.

Autonomous vehicles inevitably will be involved in accidents, raising new liability questions as to who will be responsible for a car’s “negligence.” The car manufacturer? The maker of the automation component parts, such as sensors, cameras or navigation systems? The person who was in the driver’s seat but not actually driving? All three? Litigation over autonomous vehicles is in its infancy; but we can expect negligence and product liability lawsuits, not to mention statutory claims as the government begins regulating.

Among the questions and issues that likely will arise are:

- Who is responsible if a driver falls asleep and the vehicle’s driver monitoring systems fails to wake up the driver?

- Can a driver legally rely on this feature (or lane or brake assist) and sue the manufacturer when the car does not alert him or her to a hazard?

- Should the driver be absolved of his or her own negligence?

- Can a manufacturer be subject to liability for not preventing an accident, even though its technology did not cause the harm?

- What happens when the AV follows the driving rules of the road and other drivers do not? For example, the AV:

- Drives the posted speed on the highway when the flow of traffic is faster

- Slows to a stop at a yellow light

- Stops for a full three seconds at a stop sign.

- Negligent entrustment − can an owner of an AV be liable for loaning the AV to an operator unfamiliar with the automated features and an accident occurs?

- Can a driver operate an AV while intoxicated?

Making the Rules

The immediate question is how liability will be addressed over the next several decades as we transition to the use of fully automated cars. During this period, humans and self-driving cars will share the roads and the responsibility for and control over driving decisions. Under general tort law principles, the element of control is likely to be determinative. The question of how much control the operator had or should have had over the car at the time of the accident will control in determining whether the operator could have prevented the accident.

Traditionally, car accidents are assessed through the lens of driver negligence, with the potential for product liability only when a defect in the car causes the accident or is alleged to have exacerbated the injuries. A manufacturer has never had a duty “to design an accident-proof or fool-proof vehicle.” Some suggest negligence should govern liability for car accidents, whether due to the decision-making of autonomous vehicles or human drivers. A negligence assessment would focus on whether the car’s decision or act showed a lack of reasonable care under the circumstances, not whether the computer could have been better designed. After an accident, a car’s programming can be updated to account for any new information gained to help AVs make better decisions going forward.

Analyzing a Potential Analogy

Numerous theories have been proffered on what courts can and should use as an analogy for autonomous vehicles for liability purposes. These include analogies with elevators, autopilot systems and human beings. In his book Putting the Reins on Autonomous Vehicle Liability (North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology, Vol. 19, December 2017), David King proposes we analogize AV liability with how courts handle a long history of accidents involving equine transportation. According to King, comparing autonomous vehicles with transportation by horse is a superior yet overlooked analogy for liability purposes.

Both horses and self-driving cars can perceive their environment, misunderstand their surroundings, and make dangerous maneuvers independent of the human operator’s will. For example, in Alpha Construction v. Brannon, 337 SW2d 790 (Ky. 1960), a horse walking on the side of a road was frightened by loud noises from a truck and galloped into the street causing an accident; in one of two fatal Tesla accidents in Florida in March 2019, the autonomous vehicle “saw” a white truck against a bright sky, thought it was not dangerous and drove straight into the truck.

King analogizes in both cases a failure to make what most humans would consider a common-sense interpretation of the dangers. The resulting maneuvers were caused by a lack of adequate intelligence to genuinely understand the surroundings. Horses and autonomous vehicles are property, owned and operated by regular consumers who can lend or lease them to another.

As the transportation industry evolves to embrace new technologies and products, lawyers representing clients in the industry need to understand new and changing laws, including emerging torts. Only with an understanding of potential claims and defenses can we effectively serve the ever-expanding groups of clients in litigation arising out of personal injury accidents.

/>i

/>i