Last week, an intermediate appellate court in Pennsylvania held that a jury properly awarded no compensation for a right to flood a lakefront property by an additional 5.5 feet in a heavy storm. The home on the property sat on a pad at the original elevation, so if all 5.5 feet of flooding were to occur, there would presumably be feet of water in the house. Miller v. Borough of Indian Lake, No. 1269 CD 2020 (Pa. Commw. Ct. Nov. 16, 2021)(unreported).

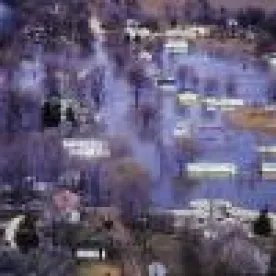

The Millers own a home on the shore of Indian Lake. A dam managed by the Borough controls the water level in the lake. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection insisted that the Borough raise the dam. As a result, the Borough required a five-and-a-half-foot increase in its flowage easement – the permitted elevation of the surface of the water in the lake behind the dam – over lakefront properties. In a heavy storm, water in the lake would rise behind a higher dam to a higher elevation, and therefore flood more of the riparian properties.

The Millers did not consent to the easement, so the Borough took it by eminent domain. The parties tried the amount of just compensation to a jury.

The Borough’s appraiser testified that the increased easement had no effect on the value of the Miller’s property. He formed an opinion of the pre-taking value of the property based upon comparable sales, but he had no comparable sales after imposition of the increased easement. Instead, he obtained data from a weather service and calculated that a storm event sufficient to raise the water level the full additional 5.5 feet would have a likelihood of 0.0004% in any one year. From that, he concluded that the low probability of any actual impact on the Millers’ property would result in no change in the property’s value.

The jury agreed. The Commonwealth Court affirmed, holding that the Millers should have cross-examined or offered their own expert.

Notice that, if the court correctly understood the testimony, the expert’s opinion does not depend at all on the comparable sales or the amount of the pre-taking value of the property. It turns only on the expert’s opinion that this taking would have no effect on value. That opinion in turn depends on an expert appraiser’s evaluation of meteorological data and its impact on flood levels in a lake.

As in boxing, the court seems to suggest that litigants must protect themselves at all times. On the other hand, the implication of the opinion appears to be that an expert appraiser can evaluate the impact of a risk of flooding or some other contingent (or perhaps not contingent) physical impact on a property without any empirical basis for the opinion, just professional judgment and experience. One wonders if that will really be the rule going forward.

/>i

/>i