Judge Jeffrey White of the Northern District of California recently dismissed toy manufacturer Tangle’s copyright and trade dress suit against fashion retailer Aritzia. The suit was brought over Aritzia’s use of sculptures resembling Tangle’s toys in its window displays. Judge White’s decision serves as a reminder that copyright protection only extends to works that have been “fixed” in a tangible medium of expression; an artist’s “[s]tyle, no matter how creative, is an idea, and is not protectable by copyright.” Tangle Inc. v. Aritzia, Inc.

Plaintiff Tangle manufactures toys that are kinetic sculptures made of seventeen or eighteen interlocking, 90-degree curved pieces. Earlier this year, Defendant Aritzia began displaying chrome pink sculptures made of eighteen interlocking, 90-degree curved pieces in its window displays. According to Tangle, Aritzia displayed “approximately 100” to “perhaps more than 300” such sculptures, which it claimed infringed the “core expression” embodied in seven of Tangle’s copyrighted works.

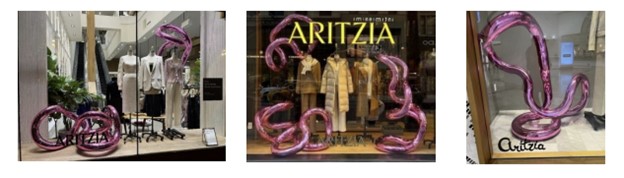

Below are images of some of Tangle’s sculptures and some of Aritzia’s window displays, taken from the Court’s decision.

Tangle’s sculptures:

Aritzia’s window displays:

On Tangle’s copyright claim, Judge White quipped that Tangle’s theory was “as pliable as its product.” Specifically, Tangle alleged all of Aritzia’s sculptures infringed all of Tangle’s copyrighted works. And at oral argument, Tangle’s counsel had stated that “any configuration” of seventeen or eighteen interlocking segments of the same size would be infringing (provided that the configuration could be “manipulated along the same axes”). Judge White noted that Aritzia’s displays varied in number of segments and positioning. So, by broadly alleging that they all infringe all of Tangle’s sculptures, Tangle was attempting to copyright its style – rather than any specific work(s) fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Further, because Tangle did not clearly define the outer bounds of the allegedly protected expression, Judge White found that it “[did] not give the Court any concrete expression to enforce.” Declining to “pin jelly on the wall,” the Court dismissed Tangle’s copyright claim with instructions that it would need to “make clear what precisely it is alleging is subject to protection, including with reference to specific copyrighted works. The ‘core’ of its various copyrighted works will not do.”

The Court granted Aritzia’s motion to dismiss Tangle’s copyright claim on an additional basis, too. Specifically, the Court found that Tangle had not adequately alleged copying of any protected aspects of its works, as would be required to state a claim for copyright infringement. Applying the extrinsic test for substantial similarity, the Court “filtered out” the unprotectable elements of Tangle’s works: 90-degree curved tubular sculptures made of interlocking pieces, the color pink, or pink chrome. Having determined these elements would not be protectable, the Court found copyright law would only protect the “selection, coordination, and arrangement” of the interlocking pieces in the sculptures. However, because there are only so many ways to arrange the segments, the copyright protection would be “thin.”

Of the pictures Tangle provided, the Court determined only one of Aritzia’s sculptures resembled a Tangle work. But it observed that there were still several differences between the sculptures (including the direction in which the loops bend, the size of the sculptures, and differences in color). Because Tangle’s sculpture was only entitled to “thin” protection, the Court found that these differences were significant. Further, Tangle never alleged that the Aritzia sculpture is kinetic or manipulable, which was an essential feature of Tangle’s works. As a result, the Court found that the Aritzia sculpture was not “virtually identical” as is required for unlawful appropriation of expression.

Turning next to Tangle’s claim for trade dress infringement, that Court dismissed it on a finding that Tangle’s operative complaint did not sufficiently define the allegedly infringed trade dress, and therefore failed to meet the “notice pleading” standard for trade dress claims. Tangle’s operative complaint stated “the Tangle design and distinctive pink-chrome color, alone or in combination with the sculptural features” was protectable trade dress. But the Court found it was not clear from the face of the complaint whether Tangle was seeking trade dress protection over “chrome pink,” segmented tubular sculptures, chrome pink segmented tubular sculptures, or some other combination of elements.

Although Judge Winter dismissed Tangle’s complaint in full, Tangle has since filed a notice of appeal to the Ninth Circuit.

Judge Winter’s determination that Tangle could not copyright an amorphous “style” is particularly notable; while this case occurred in the context of visual art, the issue of whether an artist can copyright a “style (or a “vibe” or “groove”) has come up several times in recent years in the context of music, with varying results. Most notably, a 2015 jury verdict finding the hit track “Blurred Lines” by Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams infringed Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” gained notoriety for its seemingly expansive view of the selection and arrangement theory. The verdict was upheld on appeal, though on “narrow grounds … turn[ing] on the procedural posture of the case.” Williams v. Gaye. Still, subsequent critics of the decision(including a vociferous dissent) say it risked offering copyright protection over a song’s general ‘feel,’ and what many consider to be basic building blocks of music. But since then, the pendulum seems to have swung back in the opposite direction, as in subsequent cases involving Led Zeppelin, Katy Perry, and Ed Sheeran — all of which found that while the original selection and arrangement of unprotected elements can be protectable, a protectable selection and arrangement of musical elements requires more than just cherry-picking certain unprotectable elements shared by two works that are otherwise dissimilar. Judge Winter’s decision in Tangle v. Aritzia is firmly in line with these decisions. We will have to wait and see what happens on appeal, and whether Tangle v. Aritzia will signify a trend towards a more circumscribed understanding of the selection and arrangement theory in visual art, as seems to currently exist in music.

/>i

/>i