Stepping on Toes: The Fortnite Legal Dance Battle

Victory Royale? Not quite. In a recent opinion, the Ninth Circuit held that Fortnite’s developer Epic Games might be liable for infringing a well-known choreographer’s copyrighted dance routine. In the Summer 2020 edition of Three Point Shot, we covered another Fortnite dance move copyright dispute, which ended in dismissal of the claims. This time around, however, an appeals court reversed the district court’s dismissal of the suit. Given that the Ninth Circuit has previously noted that copyright protection for choreography is “an uncharted area of the law,” this latest decision may be foundational in the area of choreography copyright law. (Hanagami v. Epic Games, Inc., No. 22-55890 (9th Cir. Nov. 1, 2023)).

Epic Games is the developer of the wildly popular video game Fortnite. Initially released in 2017, Fortnite is a free-to-play game that derives revenue from in-game purchases, such as weapons, clothing and accessories for players’ characters. Fortnite players can also purchase animated movements or dances, called “emotes,” for their characters to perform when they celebrate a victory on the virtual battlefield or during virtual concerts in the game. Epic Games regularly releases new emotes for players to purchase.

Kyle Hanagami (“Hanagami” or “Plaintiff”) is a choreographer and dance instructor who has worked with many popular musical artists. Hanagami also has a sizable social media following. He regularly posts YouTube videos featuring dancers performing his original choreography, which is how this dispute began. On November 11, 2017, Hanagami posted a five-minute YouTube video featuring groups of dancers performing a dance he choreographed to “How Long” by Charlie Puth. Hanagami registered this dance with the U.S. Copyright Office as a choreographic work.

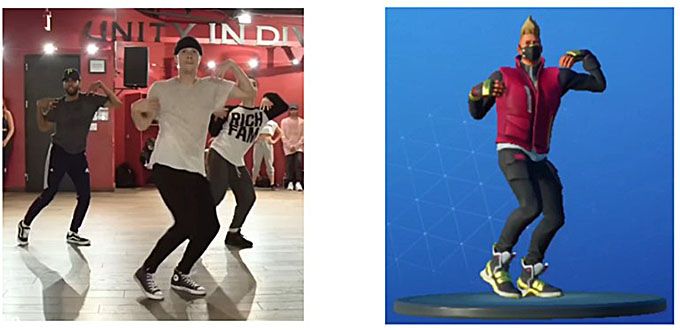

In 2020, Fortnite released a new emote called “It’s Complicated.” This emote is 16 counts and set to an original soundtrack without lyrics. In March 2022, Hanagami sued Epic Games, alleging that four counts in the “It’s Complicated” emote were copied from Hanagami’s “How Long” choreography, thereby infringing his copyright. [See the below screenshots, which were included in the appendix to the district court opinion and depict one side-by-side still image comparison of the dances]. Plaintiff’s complaint alleged that the “It's Complicated” emote contains “the most recognizable portion of [his] Registered Choreography, the portion for the hook at the beginning of the chorus of the song[.]”

Epic Games moved to dismiss the direct and contributory infringement claims, among others, arguing that the allegedly copied dance steps were not protectable elements of Hanagami’s work, and therefore, the works were not substantially similar.

In August 2022, the district court granted Epic Games’s motion to dismiss. The district court first stated that choreography, in general, is composed of “a number of individual poses,” which are not protectable “when viewed in isolation.” Further, the court determined that the dance moves at issue were unprotectable as they comprised a “small component” of Hanagami’s work, and, beyond the steps, Plaintiff had not identified other similar creative elements between the works (“Here, the two works are not substantially similar, because other than the four identical counts of poses—which are unprotected alone—Plaintiff and Defendant's works do not share any creative elements”).

Hanagami appealed the district court’s ruling, and the Ninth Circuit decided to dance with the Plaintiff, reversing and remanding the case in an opinion issued on November 1, 2023. The Ninth Circuit held that the district court erred on two fronts: first, in analyzing the elements of choreography and second, in dismissing Hanagami’s claim on the basis that the allegedly infringing dance moves were brief relative to the overall choreographic work.

On the first issue, where the district court essentially reduced choreography to mere poses, the Ninth Circuit mused…It’s Complicated. The Ninth Circuit analogized choreography to musical compositions in stating that equating choreography with “poses” is comparable to equating music with “notes.” Citing the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, the court stated that individual movements or dance steps (e.g., the basic waltz step) and “short dance routines consisting of only a few movements or steps” with only minor variations are unprotectable on their own. The Ninth Circuit went on to find that a choreographer’s selection and arrangement of poses and other elements (including transitions, timing, pauses, energy, and repetition) are what takes them from unprotectable “building blocks” to protectable choreographic works. Again, citing Copyright Office policy, the court noted the Copyright Office “does not draw a bright line distinction between copyrightable choreography and uncopyrightable dance;” rather, there is a “continuum” where works generally fall somewhere in between.

In other words, while steps and poses may form the foundational elements of choreographic works, it takes two (or more) elements to tango. As such, for a court to assess substantial similarity, they must take all of these elements, including their selection and arrangement, into account. In reducing Hanagami’s choreography to poses and ignoring the various other elements, the district court erred in holding that the works at issue were not substantially similar as a matter of law, according to the Ninth Circuit. Thus, the appeals court stated that Plaintiff’s allegations were sufficient to withstand Epic Games’s motion to dismiss because he plausibly alleged that the creative choices he made in selecting and arranging elements of the choreography are substantially similar to the choices Epic made in creating the emote.

On the second issue, the Ninth Circuit explored the question of “How Long” an allegedly infringed dance sequence must be in relation to a whole choreographic work to give rise to a finding of substantial similarity. The district court had held that the four-count segment at issue was not protectable because it comprised only a “small component” of Hanagami's overall five-minute routine and was closer to an uncopyrightable “short” dance routine. The Ninth Circuit responded by stating that there are no bright-line rules for courts to follow on this issue. Rather, it is a context-dependent question that relies on both quantitative and qualitative assessments. Further, the court stated, “if the copied portion is deemed significant, then the defendant cannot avoid liability simply because it is short.” Hanagami asserted that the sequence is qualitatively significant as the “most recognizable and distinctive” portion of the choreography, as it is keyed to the chorus of “How Long” and is repeated eight times throughout the choreography. The district court only considered the length of the sequence and failed to consider its qualitative value and, as such, the Ninth Circuit held that the district court erred in dismissing Hanagami’s claim on this basis (and that such an issue should go to a jury).

The district court also held that the dance sequence was merely an unprotectable “simple routine.” The Ninth Circuit agreed that “simple routines” are not copyrightable but stated that “short does not always equate to simple.” The Ninth Circuit held that the complexity of a dance routine that would lend it to being categorized as a copyrightable choreographic work is a question for the fact finder. In so doing, the Ninth Circuit opened the door for additional discovery and expert testimony on remand.

Choreographic works remain largely unexplored in copyright jurisprudence. As such, this case is significant because the law it develops may well serve as a foundational lens through which future choreography copyright disputes, involving both real-world and online works, will be viewed. Further, throughout its opinion, the Ninth Circuit placed great emphasis on maintaining consistency with how choreography and other categories of works of authorship, such as musical compositions, are treated in copyright cases. Thus, not only did the appeals court trip the light fantastic through the issues in this case, but it also arguably made important moves regarding this developing area of law.

Jackpot: Pennsylvania Appellate Court Pays Out for Legal Bet on Skill-Based Slot Machines

On November 30, 2023, Capital Vending Company, Inc. (“CVC”) and Champions Sports Bar, LLC (“Champions”) were the big winners when the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania affirmed a lower PA trial court decision that luck-based gaming terminals that contain a skill component allowing a player to guarantee a winning result are not illegal gambling devices. (In re: Three Pennsylvania Skill Amusement Devices, One Green Bank Bag Containing $525.00 in U.S. Currency, and Seven Receipts, No. 707 C.D. 2023 (Pa. Commw. Ct. Nov. 30, 2023)). Capital Vending and Champions Sports Bar filed a petition for return of property after the Pennsylvania State Police seized three Pace-O-Matic amusement machines (“POM Machines”), $525.00 in wagers and seven contestant receipts from Champions Sports Bar, on the grounds that the machines were gambling devices and the money and receipts were contraband derived from illegal gambling. This loss for the Pennsylvania Bureau of Liquor Control Enforcement (“BLCE”) means extra juice for Pennsylvania bars and restaurants as casual betting action (and entertaining tests of visual acuity), perhaps over a plate of hot wings or a French Dip, could skyrocket.

POM Machines are built to look like a terminal arcade game (think Pac-Man or Street Fighter), but with an interface and gameplay akin to a typical video slot machine — a 3x3 grid with various symbols and numbers (see an example of the Cavalier Game here. Source: Miele Amusements). To win, a player must match symbols in rows, columns and diagonals to win. When a player hits “Play,” the symbols are spun in a reel like a traditional slot machine and stopped. After selecting a “wild card” spot to help complete the grid, the player will achieve one of three outcomes: (1) the player wins 105% of their wager, (2) the player makes some

amount of money back that is less than 105% of their wager, or (3) the player loses the bet outright. [Watch this tutorial video from 0:23 to 1:17 for Pace-O-Matic’s own explanation].

While lady luck may favor some bettors with outcome number one in the puzzle portion of the game where winning is dependent on chance, there is a secondary game mode called “Follow Me” that lets bettors suffering from outcomes numbers two or three recoup their losing bet. “Follow Me” is a memory game, where the machine displays colored dots in a 3x3 grid and highlights them in a random pattern. The player must then repeat the pattern. If the player does so correctly, the game returns 105% of the player’s initial wager. [Watch the tutorial from 1:18 to 1:28 to see how the game works]. Thus, a sharp-eyed player can turn a POM game into a lock by perfecting the Follow Me gameplay, allowing them to win every single time.

The current regulatory action began on December 9, 2019, when the BLCE seized the POM Machines, cash, and receipts from Champions following an investigation, which concluded that these games were slot machines rather than “skill games.” Under Pennsylvania state law, only licensed gambling operators, like racetracks and casinos, can operate slot machines and a person is guilty of a first-degree misdemeanor if he "intentionally or knowingly makes, assembles, sets up, maintains, sells, lends, leases, gives away, or offers for sale, loan, lease or gift, any punch board, drawing card, slot machine or any device to be used for gambling purposes, except playing cards." 18 Pa.C.S. § 5513(a). The law also allows the state to seize any gambling device that is used in violation of the provisions of the statute. See 18 Pa.C.S. § 5513(b). While no criminal charges were filed related to the seizure, the Pennsylvania Attorney General (“AG”) subsequently issued an administrative citation to Champions for permitting gambling.

Apparently, the Champions seizure was merely one of many enforcements at the county level in Pennsylvania, and some of those previously hadbeen challenged in court on the basis that “skill games” are not expressly regulated under the state gambling law and its taxing regime. Thinking the odds were decent to overturn the seizure order, in August 2022 Champions and CVC fought back in trial court, arguing that the machines seized by BLCE are not gambling devices but are instead predominately skill games. The bell rung on March 23, 2023 when a Dauphin County trial court granted CVC’s petition for return of the property. The lower court stated that for the POM Machines to be gambling devices they must have the three elements of gambling, namely: 1) consideration; 2) chance; and 3) reward. While the court found the machines had elements of consideration (players deposit money) and reward (players can win more than they bet), it found the games were “predominately games of skill” because “a patient and skillful player could win at least 105% of the amount played on each and every play by utilizing the Follow Me feature.” While the “puzzle portion of the game [i]s predominately reliant on chance,” the Follow Me element “eliminates the element of chance that is present in the puzzle portion by giving a player the opportunity to win back the money that they lost by utilizing skill.”

The AG doubled down on appeal, arguing that under the Pennsylvania Crime Codes: (1) the POM Machines are “slot machines” and (2) POM Machines are gambling devices per se.

In its November 30th decision, the appellate court evaluated the actual POM Machine game play against the AG’s arguments that they are “slot machines” and inherently illegal gambling devices. Because the Pennsylvania Crime Code lacks its own definition of “slot machines,” the court relied on the dictionary definition finding that a “slot machine” means a “‘coin-operated gambling machine that pays off according to the matching of symbols on wheels spun by a handle,’” including both mechanical and electronic machines. While the court noted the first stage in POM Machine gameplay “may be analogous to the experience that a slot machine offers,” POM Machines integrate the “Follow Me” memory feature into the overall gameplay and therefore are distinguishable from the traditional slot machine.

The Pennsylvania Crime Code also has a catch-all category to make devices “used for gambling purposes” illegal. To prevail under this section, the AG argued that there was a specific nexus between the POM Machines and illegal gambling because (i) the game was advertised as a slot machine, (ii) the “Follow Me” feature is “insignificant,” “tedious,” and “difficult,” and (iii) the main gameplay is luck-based. According to the AG, “chance far outweighs skill when the game in its entirety is considered.” In response, CVC and Champions relied on the lower court’s holding that skill predominates over chance in gameplay and that the Follow Me game phase was mischaracterized by the AG.

When the reels came to a stop, the edge went to CVC and Champions. The court stated that Pennsylvania’s rule is based on precedent holding that a game is a gambling game if the element of chance predominates over the element of skill. As the court noted, if a player can exercise skill to win on every wager, the game is predominantly skill-based, even though the skill-based portion of the game only constitutes a portion of the overall gameplay. As described above, a memory-based skill game following a traditional chance-based game lets a clever player who won less than 105% of the amount played use his or her skill to win on every wager on the POM Machines at issue. In fact, a player can even improve their ability to succeed at “Follow Me” by practicing pattern recognition and memory skills (though, partaking in happy hour festivities at the game sites may impair such skills and one’s chance of beating the “Follow Me” game portion). Still, no matter how bad a player’s luck is at the first stage, they have a permanent hedge with “Follow Me.”

Ultimately, the court ruled that POM Machines are neither “slot machines” nor inherently gambling devices, affirming CVC’s and Champions’ petition for return of the property. This is a big victory for Pennsylvania restaurants, bars, convenience stores, fraternal clubs and other non-gambling-related businesses. Recently, the skill vs. luck debate around sports gambling generally has resolved in the house’s favor, as sports betting is currently legally offered in 37 states. This ruling may have a multiplier effect as Pennsylvania and other states might undertake fewer crackdowns against skill-based games in non-gambling establishments. It was also reported that the Pennsylvania legislature is considering legislation that would cover these skill games.

Regardless, it’s not game over yet as reports suggest that the attorney general may appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

In Wake of Hazing Investigation, Judge Denies Boston College Swimming and Diving Team’s Request to Reverse Suspension

On October 26, 2023, a Massachusetts judge denied the requests of 37 members of the Boston College Swimming and Diving Team (the “Plaintiffs” or “Team”) to reverse the indefinite suspension of the Team that was first announced in September 2023, following what Boston College Athletics called “credible reports of hazing.” (Does 1-37 v. Trustees of Boston College, No. 2381CV02900 (Mass. Super. Ct. Oct. 26, 2023)).

The Team members claimed that they were irreparably harmed when the Trustees of Boston College and Boston College Athletics officials (collectively, “Defendants” or the “University”) “arbitrarily” imposed a blanket suspension without conducting a complete investigation of an apparent hazing incident at an annual “Frosh” event on September 3, 2023, where Team members allegedly coordinated binge drinking activities involving freshmen. On September 20, 2023, Boston College made a public statement on the Boston College Athletics website noting that the University had “determined that a hazing incident had occurred” involving the Team; the University later updated the statement to say that there were “credible reports of hazing.” According to the University, its initial investigation involved interviews with 20 members of the Team, as well as review of photos, videos and group chat messages. By the time the decision was made to suspend the Team, the Defendants had apparently been made aware of various Team events that occurred between September 2-4, 2023, which allegedly involved underage drinking. For example, the “Frosh” event, which is an apparent annual tradition for the Team, featured organized activities for freshmen Team members, but also allegedly involved initiation of freshmen to the Team by upperclassmen that resulted in reports of excessive drinking (as well as vomiting and passing out).

Boston College Athletics deemed such activities “hazing.” Boston College and Boston College Athletics, in relevant student policies, prohibits hazing, which is also a crime in Massachusetts (G.L. c. 269, § 17). Student and Athletic Department policy broadly defines hazing to include “any activity or abuse of power by a member of an organization and/or group used against any individual or group of individuals as a condition to affiliate with ... (or to maintain full status in [the] group), that humiliates, degrades, or risks emotional and/or physical harm, regardless of the subject's willingness to participate,” and expressly states that hazing may also involve “implied coercion.” In addition, according to the University, there had been reports of a Team hazing incident back in spring 2022. Thus, on September 20, 2023, Boston College Athletics issued a statement that the Team had been “placed on indefinite suspension.”

On October 17, 2023, the Plaintiffs filed their complaint while also seeking injunctive relief to reinstate the program based on a selective enforcement claim brought under Title IX of the Education Amendment of 1972. Principally, the Plaintiffs claimed that all-male University teams have faced similar allegations involving excessive underage drinking but “were not imposed a disciplinary sanction prior to ‘an investigation process that amounted to more than what the Plaintiffs in the instant matter received.’” The Plaintiffs’ memo in support of its injunction request asserted that the decision to suspend the Team “was likely motivated by the fact that [the Team] is a co-ed program.” The Plaintiffs also stated that the University violated its own policies by imposing an “unprecedented and unwarranted” indefinite suspension of an entire sports program during the pendency of a conduct investigation by Boston College Athletics. Finally, the Plaintiffs argued that without an order reinstating the program, the team members would lose out on competitive opportunities and suffer irreparable harm to “their entire swimming careers.” The Defendants argued that Boston College Athletics’ decision to indefinitely suspend the Team was both warranted and within its Athletic Director’s discretion. In its opposition brief, Defendants countered that the “decision to suspend team activities had nothing to do with the fact that the team is co-ed. Nor is there any case involving ‘similar circumstances’ involving an all-male team known to the University.” The University also argued that the evidence gathered in the initial investigation was “sufficient” to make a finding that hazing occurred, which “warranted the team-suspension,” with individual student discipline to be later adjudicated “through the student conduct process.”

The court was unswayed by the Plaintiffs’ arguments and denied their motion for a preliminary injunction to reinstate the Team. The court stated that the Plaintiffs’ claims of selective enforcement of a disciplinary sanction on their co-ed sports team were based on allegations made only “upon information and belief,” not firsthand knowledge, and thus were insufficient to establish a likelihood of success on the merits of the Title IX claim.

The Plaintiffs also failed to convince the court that they were likely to succeed on the merits of their other claims, which included breach of contract, denial of fairness, defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. After reviewing the materials presented, the court concluded that the University’s suspension was not “arbitrary and capricious” in light of a prior 2022 hazing incident, and the fact that the upperclassmen on the Team had been repeatedly warned that student-athlete hazing was prohibited by Boston College Athletics, Team rules and Massachusetts law and could result in “serious consequences.” As the court found that the University’s submissions substantiated their public announcement that hazing had occurred, the Plaintiffs’ defamation claims were also found insufficient at this point to warrant injunctive relief. Additionally, since the Plaintiffs failed to show that the Defendants acted unlawfully or showed a likelihood of success on the merits, the court determined that it was unnecessary to address the question of irreparable harm.

On October 27, 2023, one day after the court’s ruling, the Plaintiffs filed a notice of discontinuance of the action without prejudice, given that the goal of the court action was to reinstate the program pending further investigation by the University. For the moment, the Plaintiffs have decided to end their legal challenge and have expressed hope that the University decides to lift the suspension at some point in the future.

Jason Krochak, Christine G. Lazatin, Joseph M. Leccese, Adam M. Lupion, Jon H. Oram, Kevin J. Perra, Bernard M. Plum, Howard Z. Robbins, Bradley I. Ruskin, Bart H. Williams, Caroline E. Rimmer, Alexander J. Amir and Sabrina Palazzolo contributed to this article.

/>i

/>i