Over the past two and a half months, auditors of the largest publicly traded companies have communicated Critical Audit Matters (CAMs) in their audit reports.[i] CAMs are “the things that keep the auditor up at night”—those matters that involve especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment.[ii] According to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), these new disclosures were needed to reduce the information asymmetry between investors and auditors, which should, in turn, reduce the information asymmetry between investors and management about the company’s financial performance.[iii]

Not surprisingly, companies and their auditors expressed concerns that reporting CAMs would increase litigation risk. Although the PCAOB made a number of changes to address those concerns, it noted that most of those who raised the issue “continued to express varying degrees of concern about the potential for increased liability, either for auditors or for both auditors and companies.”[iv]

Now that the new requirement is in effect is shareholder litigation related to CAMs on the horizon? To shed light on that question, this article discusses whether a stock price decline may be attributable to a CAM, based on the types of CAMs that have recently been disclosed for the largest publicly traded companies. It also discusses whether Lorenzo v. SEC has the potential to increase the number of CAM-related claims.

Could a stock price decline be attributable to a CAM?

A review the audit reports for 57 large accelerated filers for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2019, disclosed four aspects of CAMs—the “What, Why, How, and Where.”[v]

Required CAM Disclosures |

|

|

What |

Identify the CAM. |

|

Why |

Describe the principal considerations that led the auditor to determine that the matter |

|

How |

Describe how the CAM was addressed in the audit. |

|

Where |

Refer to the relevant financial statement accounts or disclosures that relate to the CAM. |

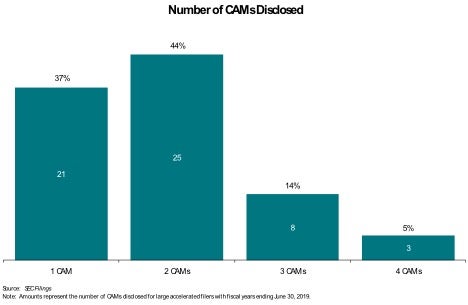

The auditors for these large accelerated filers most often identified two CAMs in their audit opinions. Auditors frequently identified one CAM, and the maximum number of CAMs identified was four.

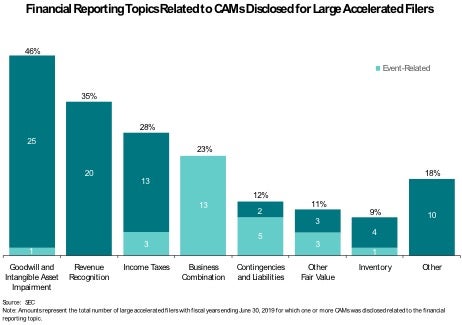

Although all of the CAMs identified by the auditors relate to financial statement amounts and disclosures, some were tied to specific transactions or events (“event-related”).

The most commonly reported CAM, for nearly half of the accelerated filers, was the assessment of whether an impairment charge for goodwill and/or other intangible assets was needed. The vast majority of auditors cited the significant judgment required to estimate the fair value of the relevant asset (e.g., estimating future revenue to evaluate goodwill for impairment) as a principal consideration that led to identifying the impairment of goodwill and other intangible assets as a CAM.

Revenue recognition was identified as a CAM for approximately one in three accelerated filers. Auditors cited a variety of revenue recognition judgments as principal considerations that led to identifying revenue recognition as a CAM. For example, auditors cited to judgments related to the timing of revenue recognition under the percentage of completion method or from contracts with multiple performance obligations.

Income taxes represented a CAM for just over one in four accelerated filers. Auditors most frequently cited the complex judgment and skills required to evaluate uncertain tax positions, including the company’s disclosures of contingent liabilities associated with those tax positions, as a principal consideration that led to identifying income taxes as a CAM.

The PCAOB envisions that CAMs may assist investors in assessing the “credibility” of the financial statements and, in certain instances, the quality of the audit.[vi]

Plaintiffs may relate a stock price decline following the announcement of a restatement or write-down to alleged omissions or material misstatements in a previously disclosed CAM. In recent years, the frequency of restatements has been relatively low.[vii] However, three out of the five largest securities class action settlements in 2018 involved financial statement restatements.[viii] Settlements were larger for cases involving write-downs, such as impairment of goodwill or other intangible assets, than for cases that involved other types of accounting allegations in 2018.[ix]

In addition, for CAMs that are tied to specific transactions or events, plaintiffs may claim that a stock price decline associated with a related event is attributable to the CAM.[x] For example, the disclosure of an adverse ruling by the IRS may be followed by a stock price decline that plaintiffs relate to a material misstatement in prior CAM-related disclosures on uncertain tax positions. Plaintiffs could also attempt to tie a stock price decline to an alleged omission when prior CAM-related disclosures did not discuss uncertain tax positions. For 21 of the large accelerated filers (37 percent), at least one CAM was event-related. The most common event was a business combination during the last fiscal year. Additional events that were tied to CAMs include divestitures and lawsuits.

Will Lorenzo v. SEC increase the number of CAM-related claims?

The PCAOB acknowledged that CAM disclosures could result in litigation, that the risk of litigation could be heightened if the auditor disclosed original information about a company, and that the communication of CAMs could affect management disclosures. In other words, the PCAOB recognized that CAM disclosures had the potential to disrupt the traditional U.S. regulatory framework, in which management provides information regarding the company and the auditor opines on the compliance of that information with applicable financial reporting guidelines.[xi]

In its final standard, the PCAOB explained that the auditor is not expected to provide information that has not been made publicly available by the company unless the information is necessary to describe the principal considerations that led the auditor to determine that a matter is a CAM or how the matter was addressed in the audit. The PCAOB required the auditor to provide a draft of the auditor’s report to the audit committee and to discuss the draft with them. The PCAOB also acknowledged the need for the auditor to discuss the treatment of any sensitive information with the audit committee and management.[xii]

The final standard was issued on June 1, 2017, at which time liability under securities laws for a false statement was limited to the “maker” of the statement, in accordance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2011 Janus decision.[xiii] The Court’s recent decision in Lorenzo v. SEC in March of this year may have changed that. In overturning the decision in Janus, the Lorenzo ruling established that an individual could be held liable for a false statement, even if that individual was not the “maker” of the false statement, but rather was found to have disseminated the false statement with intent to deceive.[xiv]

Various rulings, including the Supreme Court’s decision in the Omnicare matter, have largely isolated auditors from liability in securities cases given that the auditors are expressing opinions.[xv] However, the CAM disclosures may be interpreted by plaintiffs as rising to a level beyond opinions.[xvi] Furthermore, the Lorenzo decision has the potential to expose auditors to additional CAM-related claims. In particular, plaintiffs could seek to hold auditors liable for management’s financial statements and disclosures referenced in or related to the CAMs.

The implementation of CAM disclosures in a post-Lorenzo world also has the potential to expose companies to CAM-related claims. For example, to the extent CAMs are discussed on investor conference calls,[xvii] companies could find themselves providing CAM-related details that may be used as a basis for potential claims.

Looking ahead

The PCAOB adopted a phased approach whereby auditors of large accelerated filers reported CAMs for fiscal years ending June 30, 2019. The auditors of all other companies to which the requirements apply are required to report CAMs for fiscal years ending on or after December 15, 2020. The full effects of CAM disclosures on shareholder lawsuits may take some time to develop.

Even if there is an increase in litigation, it remains to be seen whether claims involving CAMs would survive a motion to dismiss.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors, who are responsible for the content, and do not necessarily represent the views of Cornerstone Research. This article was first published by Law 360.

[i] Publicly traded companies are considered large accelerated filers if their public float (i.e., aggregate worldwide market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates) is $700 million or more as of the last business day of their most recently completed second fiscal quarter. See 17 CFR 240.12B-2 – Definitions. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board required the disclosure of CAMs for large accelerated filers for audits of fiscal years ending on or after June 30, 2019.

[ii] See PCAOB Staff Guidance, Implementation of Critical Audit Matters: A Deeper Dive on the Determination of CAMs – Insights for Auditors, Mar. 18, 2019, p. 1, https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Documents/Implementation-of-Critical-Audit-Matters-Deeper-Dive.pdf. The PCAOB defines a CAM as “a matter that was communicated or required to be communicated to the audit committee and that: (1) relates to accounts or disclosures that are material to the financial statements and (2) involved especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment” (PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, June 1, 2017, p. 11).

[iii] PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, June 1, 2017, p. 65, https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Docket034/2017-001-auditors-report-final-rule.pdf.

[iv] Ibid., p. 40.

[v] The 57 annual filings by large accelerated filers with a year-end of June 30, 2019, as of September 20, 2019, included three form 20-Fs by foreign issuers. PCAOB Staff Guidance, Implementation of Critical Audit Matters: A Deeper Dive on the Communication of CAMs – Insights for Auditors, May 22, 2019, p. 1, https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Documents/Implementation-Critical-Audit-Matters-Deeper-Dive-Communication-of-CAMs.pdf.

[vi] PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, June 1, 2017, p. 67, https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Docket034/2017-001-auditors-report-final-rule.pdf.

[vii] Audit Analytics, 2018 Financial Restatements An Eighteen Year Comparison, August 2019; Audit Analytics, 2018 Financial Restatements Review, Aug. 28, 2019, https://blog.auditanalytics.com/2018-financial-restatements-review/.

[viii] Cornerstone Research, Accounting Class Action Filings and Settlements: 2018 Review and Analysis, p. 15, https://www.cornerstone.com/Publications/Reports/2018-Accounting-Class-Action-Filings-and-Settlements.

[ix] Ibid., p. 18.

[x] Recent increases in shareholder class actions have been attributed to a rise in “event-driven” litigation. At the same time, the law firms that have been associated with those cases are also involved in accounting cases. See Rachel Graf, Filing-Happy Law Firms Not Limited to Event-Driven Claims, Law360, Apr. 17, 2019, https://www.law360.com/articles/1150820/filing-happy-law-firms-not-limited-to-event-driven-claims.

[xi] PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, June 1, 2017, pp. 17, 32–33, 41, 93, https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Docket034/2017-001-auditors-report-final-rule.pdf.

[xii] Ibid., pp. 34–35.

[xiii] Janus Capital Group v. First Derivative Traders, 564 U.S. 135 (2011).

[xiv] Lorenzo v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 139 S. Ct. 1094 (2019).

[xv] Omnicare Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015).

[xvi] David M. Fine and Christina M. Conroy, New “Critical Audit Matter” Reporting Requirement Presents Challenges for Independent Auditors and Public Company Audit Committees, Bloomberg BNA, Tax and Accounting Center, Nov. 29, 2017.

[xvii] The Center for Audit Quality (CAQ) stated that “[c]ompanies can prepare for questions about CAMs from investors by understanding the auditor’s responsibilities with respect to identifying and communicating CAMs and understanding why the auditor determined particular matters to be CAMs. . . . Management may also want to identify who within the company will address any questions regarding CAMs from investors or other stakeholders” (Center for Audit Quality, Critical Audit Matters: Lessons Learned, Questions to Consider, and an Illustrative Example, December 10, 2018, p. 5). The CAQ “is dedicated to enhancing investor confidence and public trust in the global capital markets. . . . An autonomous, nonpartisan, and nonprofit public policy advocacy organization, the CAQ guides and supports the public company auditing profession as it does its vital work worldwide” (Center for Audit Quality, Our Mission, https://www.thecaq.org/about-us/) .

/>i

/>i