The bill aims to eliminate all “non-essential” uses of PFAS with a 10-year deadline.

What is the FCRAA?

The FCRAA tasks the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) with reviewing the persistence, bioaccumulation, and human health risks of the various PFAS. It also requires NASEM to identify current PFAS uses and provide the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with guidance on classifying uses as “essential” or “non-essential.” This is in contrast to a bill currently before the California Senate that would, by itself, set strict limits on what might be classified as a “currently avoidable use.” If the bill is passed, PFAS manufacturers and users would be required to petition EPA to designate the use of PFAS in their products as essential, file reports with EPA to disclose certain information relating to PFAS (including non-essential uses and viable alternatives), and submit their own phaseout schedule where applicable. The term “manufacturers” includes any person who imports or exports products containing PFAS. The term “users,” however, has yet to be defined. While some state PFAS regulations focus on consumer goods, there appears to be no such limitation in the FCRAA.

The bill establishes accelerated deadlines to eliminate non-essential uses of PFAS in certain classes of products (e.g., rugs, furniture, juvenile products) and a 10-year national deadline to eliminate non-essential PFAS uses in all other products, subject to certain exceptions.

On the litigation front, the bill would toll state statutes of limitation and statutes of repose for newly designated hazardous substances, like PFAS, until the later of (1) the date which the substance was designated as a hazardous substance or (2) the date when the plaintiff knew or reasonably should have known that their injury was caused by the hazardous substance. It would also aim to prevent large corporations from “exploiting bankruptcy procedures” to avoid legal claims.

State Law Developments

While the bill would be the first national legislation aimed at PFAS, several states have introduced similar legislation over the past few years. Notably, recent laws passed in Minnesota and Maine prohibit intentionally added PFAS under their own timelines, setting deadlines in 2032 and 2030, respectively. Other legislation is still in the works. For example, California has two bills addressing PFAS currently making their way through the legislature. We reported on these two California bills in a recent client alert, which is available here.

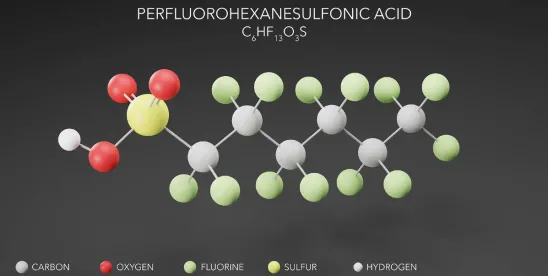

The day after the federal bills were introduced, EPA announced a final rule that designates perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) — two widely used and highly persistent PFAS phased out by 2015 — as “hazardous substances” under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). It also empowers EPA to investigate and clean up PFAS releases, while ensuring that leaks, spills, and other releases are reported. A full breakdown of the final rules can be found here.

Recent high-profile lawsuits give context to the FCRAA’s and EPA’s focus on litigation. In 2023, lawsuits against manufacturers related to PFAS in public water systems culminated in settlements totaling $11 billion, followed by an award of $956 million in legal fees to the plaintiffs’ attorneys. Lawsuits against consumer product manufacturers for alleged PFAS in their products are also on the rise. For example, a 2023 class action lawsuit against celebrity-owned Prime Hydration, alleging the company’s energy drink contains PFAS, has been garnering public discussion recently. Similar allegations have been brought in class action suits against other beverages, including Bolthouse Farms’ “Green Goodness” smoothies and some Biosteel sports drinks.

Next Steps

PFAS are not just for non-stick cookware. They are found in everything from carpets, clothing, cosmetics, and food packaging to paints, plastics, electronics, ski wax, and beyond. Consumer product manufacturers should keep abreast of these developments in the law, as they could have far-reaching implications for their businesses, including not only regulatory compliance and litigation, but also sourcing, design, and insurance, to name but a few issues affecting consumer products manufacturers.

/>i

/>i