After the landmark prices received for eight offshore wind leases in the New York Bight, and with great anticipation for the upcoming December 5, 2022, lease auction for the Humboldt and Morro Bay Wind Energy Areas (WEAs) off the coast of California, the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) is turning its sights to the Gulf of Mexico. The Biden Administration’s announced goal of developing thirty (30) gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind energy by 2030 now includes two WEAs in the Gulf of Mexico with the potential of producing up to 3 GW of power.

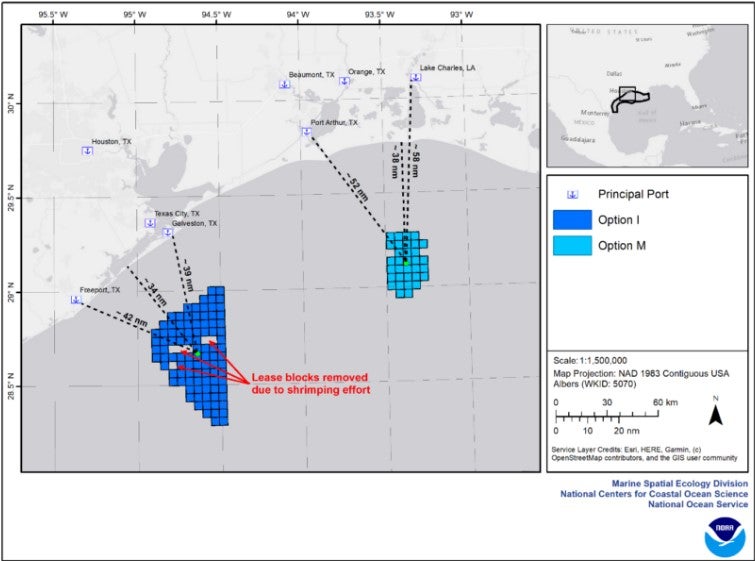

Specifically, on October 31, 2022, BOEM announced that it had finalized the first two WEAs in the Gulf of Mexico, comprising of over 500,000 acres 24 nautical miles off the coast of Galveston, Texas, and almost 175,000 acres 56 nautical miles off the coast of Lake Charles, Louisiana. BOEM expects to issue a Proposed Sale Notice for the Galveston (Option “I”) and Lake Charles (Option “M”) WEAs by late 2022 or early 2023. The announcement follows several years of planning and public consultation with stakeholders in the region including Tribes, local and state governments, fishing and shrimping interests, the maritime and oil & gas industries, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), and the U.S. Coast Guard (Coast Guard).

Opportunities[1]

In 2020, BOEM and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) published a study on the technical feasibility and economic potential of offshore wind development on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) in the Gulf of Mexico (BOEM/NREL Study).[2] The study identified a number of advantages to the development of offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico, including shallow water, mild climate and sea states, and, most important, proximity to the well-developed oil and gas supply chain.

Shallow Water and Mild Prevailing Conditions. The BOEM/NREL study determined that the Gulf of Mexico has 32% of the shallow ([3] Additionally, the Gulf of Mexico has a milder climate and calmer sea state than offshore wind areas such as the North Sea and the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of the United States, which will allow SOVs and other vessels to operate year-round and will significantly increase turbine accessibility compared to other areas with more severe weather, resulting in higher turbine availability and lower operation and maintenance costs over the turbines’ lifetimes.

Proximity to Oil and Gas Supply Chain. One of the key advantages to the development of offshore wind in the Gulf of Mexico is the potential for leveraging and repurposing the existing oil and gas infrastructure, supply chain and labor force. As BOEM’s Director, Amanda Lefton, said, the Gulf area has “a mature industry base and the know how to advance energy development in the OCS.”[4] Gulf Coast shipyards and large component steel fabrication facilities have begun to play a vital role in its development. For example, the steel jacket foundations for the first commercial offshore wind farm in the United States, Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island, were made at Gulf Island Fabrication, Inc. in Houma, LA.[5] Additionally, Dominion Energy is building the first Jones Act-compliant offshore wind turbine installation vessel in Brownsville, TX,[6] and Edison Chouest is building the first Jones Act-compliant Service Operations Vessel at its shipyards in Florida, Mississippi and Louisiana.[7] Area seaports that could be utilized for offshore wind operations with relatively minor modifications, and an experienced onshore and offshore labor force are anticipated to result in lower material and labor costs than in other regions where offshore wind is being developed, such as the Pacific Coast and the Northeast.

Challenges

The expansion of offshore wind into the Gulf of Mexico is not without its challenges. As discussed in the BOEM/NREL Study, the higher prevalence of significant hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico compared to the Northeast and the Pacific Coast, combined with softer seabed soil characteristics, could increase turbine and substructure costs. BOEM has stated that it is working with industry to ensure that offshore wind turbines will be able to withstand a Category 5 hurricane. The risks associated with hurricanes could also affect insurance costs and insurability of facilities located in the Gulf of Mexico, which developers will need to consider in their economic modelling. Additionally, in comparison with European or US offshore wind sites in the North Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico has lower annual average wind speeds (similar to the South Atlantic region) that may necessitate new turbine designs optimized to operate in these conditions, e.g., increased rotor diameters, lower solidity blades, and more intelligent control strategies.

State Activities

The State of Louisiana has been active in promoting offshore wind development. BOEM’s Gulf of Mexico Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force was established in 2021 at the request of Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards. The January 31, 2022, Louisiana Climate Action Plan announced a goal of 5GW of offshore wind development by 2035. In June 2022, Governor Edwards signed Act 443 into law, which created a framework for wind leases in Louisiana state waters (up to three nautical miles from its coastline) and gave the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources the authority to promulgate rules and regulations relating to wind energy leases in state waters, including the setting of rent or royalty amounts. The first sale of leases in Louisiana state waters could take place by the end of 2023. Other efforts toward the development of offshore wind off the coast of Louisiana include the launch of the Louisiana Wind Energy Hub at the University of New Orleans in August 2022, which is intended to help train workers for the energy transition and accelerate the offshore wind ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico.

Texas’ storied experience with respect to onshore wind development should benefit offshore wind development in the Gulf of Mexico. Texas has the largest onshore wind energy fleet in the U.S., with over 37 GW of capacity, which translates to almost 21% of energy capacity statewide and over 26% of all U.S. wind capacity.[8]

Process

As discussed above, BOEM released the final WEAs on October 31, 2022, following an extensive public comment period. The WEAs were identified by BOEM using an ocean spatial planning tool in collaboration with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which characterized areas with the lowest likelihood of conflict with other ocean activities and the highest suitability for offshore wind development. In response to comments from the shrimping industry, DOD and the US Coast Guard BOEM reduced the size of the WEAs from the draft WEAs proposed in July 2022.[9]

The next step in the leasing process will be the release of a Proposed Sale Notice (PSN) with a 60 day comment period, which is expected to take place later in 2022 or early 2023. That will be followed by a Final Sale Notice (FSN) based on feedback to the PSN, which will set out the terms of the competitive auction and certain stipulations for leases in the WEAs.

Evidence from the recent auction for wind leases in the New York Bight, as well as the FSN for the upcoming Morro Bay and Humboldt WEAs in the Pacific, shows a general trend towards requiring earlier, more frequent, and more comprehensive stakeholder engagement, especially with Tribes and fishing interests, as well as the use of non-cash bid credits to incentivize lessees to invest in supply chain development and in local communities affected by wind developments (e.g., workforce training, contributions to offshore wind vessel development, and Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) with affected communities).[10] Developers should expect to see many of the same types of bidding mechanics and lease stipulations in the PSN for the Gulf WEAs.

FOOTNOTES

[1] The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act, with its enhanced renewable energy tax credits, should work to further incentivize the development of offshore wind energy capacity. For a full discussion of the tax credits, see “Tax Law Changes in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (H.R. 5376)”.

[2] BOEM OCS Study, Offshore Wind in the US Gulf of Mexico: Regional Economic Modeling and Site Specific Analyses, BOEM 2020-018 (February 2020) (BOEM_2020-018.pdf).

[3] BOEM Memorandum, Request for Concurrence on Preliminary Wind Energy Areas for the Gulf of Mexico Area Identification Process Pursuant to 30 C.F.R. § 585.211(b), pages 39 and 43 (Draft Area ID Memo (boem.gov)).

[4] BOEM Press Release (October 31, 2022) (BOEM Designates Two Wind Energy Areas in Gulf of Mexico | Bureau of Ocean Energy Management).

[5] Press release (November 11, 2014) (Gulf Island Fabrication, Inc. Announces Project Contract :: Gulf Island Fabrication, Inc. (GIFI)).

[6] Texas Monthly, May 2021 edition, America’s Offshore Wind-Powered Future Begins in a Texas Shipyard – Texas Monthly.

[7] Press Release (March 3, 2022) (Construction Begins on a 260-Foot Wind-Farm Service Operations Vessel (chouest.com).

[8] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 3rd Quarter 2022, WINDExchange: U.S. Installed and Potential Wind Power Capacity and Generation (energy.gov)

[9] See fn 3.

Steve Peterson also contributed to this article.

/>i

/>i