False advertising litigation typically revolves around two questions:

1. Did the allegedly false advertising have any impact on purchasing behavior?

2. If it did, what was the defending brand’s unfair gain?

In preparing for litigation, attorneys often employ consumer research experts to answer the first question and damages experts, i.e., economists, forensic accountants, corporate finance professionals, etc., to answer the second question.

This article describes a consumer research methodology that not only detects the presence of impact, but is also capable of quantifying the potential gain associated with allegedly false claims.

The Setting

The Research Design

The methodology proposed here employs a test vs. control design using samples of the defending brand’s customers (e.g., bought in the last X number of months). None of the products are branded in the test.

The test brand is represented by a complete list of attributes or benefits, including those contested in the litigation as being false or misleading. The control product lists the same attributes less the allegedly false claims or including versions of the claims using language that would not have caused the plaintiff to launch the suit in the first place.

The design is implemented via an online survey of defendant’s customers. Survey respondents in both groups are instructed to imagine themselves shopping for the product category using the list of attributes as a cue and to indicate their preference by choosing a point on the 5-point purchase likelihood scale shown below.

Very likely to buy — Somewhat likely to buy — Neither likely nor unlikely to buy —

Somewhat unlikely to buy — Very unlikely to buy

The Gain Factor

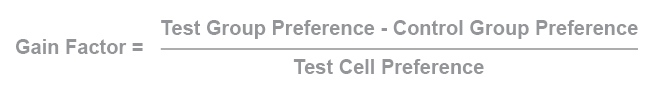

The proportion of respondents who rate the brand in the top two boxes, i.e., very and somewhat likely to buy, obtained in the test and control groups are categorized as customers who prefer the brand described by the list of attributes presented to them. Based on these results we can derive a gain factor due to the alleged false advertising using the formula:

The formula states that the gain accruing to the defendant’s brand is equal to the net impact of the falsely advertised content as a proportion of the preference caused by the allegedly false advertising.

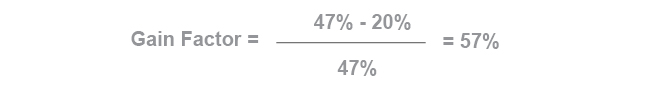

The gain factor answers the question: What proportion of the preference for the misleading brand is due to the false claims made in its marketing communication? For example, if the preference in the test group turns out to be 47 percent and the preference in the control group is 20 percent, then the gain factor is calculated as:

This result indicates that the false advertising being contested here is responsible for 57 percent of the total preference of the allegedly infringing brand.

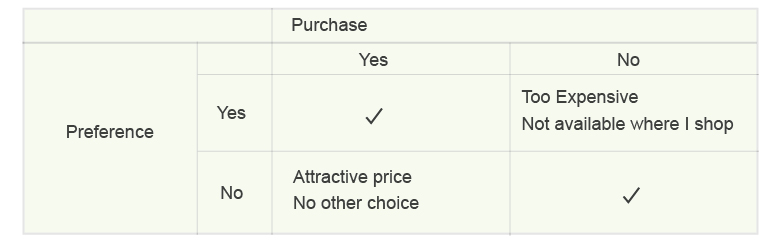

Table 1 The Relationship Between Preference and Purchase

This boils down to two main reasons for behavior deviating from preference: availability and price. Otherwise, one would expect to see complete congruence between preference and purchasing. Neither limited availability nor unreasonable price should create a significant difference between preference and purchase in a developed economy with a robust competitive environment.

Based on that, it appears that in the long-run, the brand preference data obtained in surveys can be applied directly to the “ill gotten” revenue estimation at the heart of damages calculations.

Summary

While consumer research cannot directly estimate the transfer of sales, revenue, or profits from one brand to another or the supposedly ill-gotten profits that may be due to false claims, it can estimate the preference shift due to the points communicated by the allegedly false advertising compared to an identical bundle of benefits that does not contain the disputed benefits. As discussed above, preference gains constitute a valid measurement of purchasing.

/>i

/>i