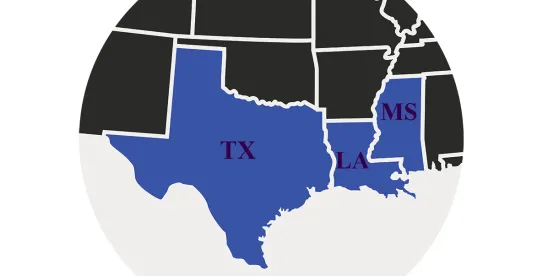

In a case brought by a group of record labels against an internet service provider (ISP) for contributory copyright infringement of more than 1,400 songs, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that the provider, which knew how its product would be used by subscribers, could be contributorily liable for its subscribers’ actions, but that because the record companies registered albums – not individual songs – with the US Copyright Office, statutory copyright damages were not available for each infringed song. UMG Recordings, Inc. et al. v. Grande Communications Networks, LLC, Case No. 23-50162 (5th Cir. Oct. 9, 2024) (Higginson, Higginbotham, Stewart, JJ.)

The plaintiffs are a group of major record labels, while the defendant, Grande Communications Network, is a large ISP. To combat copyright infringement among individuals using peer-to-peer file-sharing networks such as BitTorrent, the plaintiffs used a third-party company, Rightscorp, to identify infringing conduct by engaging with BitTorrent users, documenting that conduct, and using the information to notify ISPs of its findings so that the ISPs could take appropriate action. However, for nearly seven years Grande did not terminate subscribers for copyright infringement but merely notified them of a complaint. In the district court, a jury found Grande liable for contributory copyright infringement of more than 1,400 of the plaintiffs’ sound recordings. The jury found that the infringement was willful and awarded nearly $47 million in statutory damages. Grande appealed.

The Fifth Circuit explained that to prove direct infringement by Grande’s subscribers, the plaintiffs had to show “(1) that Plaintiffs own or have exclusive control over valid copyrights and (2) that those copyrights were directly infringed by Grande’s subscribers.” To meet the elements of secondary liability for subscribers’ conduct, “Plaintiffs had to demonstrate (3) that Grande had knowledge of its subscribers’ infringing activity and (4) that Grande induced, caused, or materially contributed to that activity.”

In analyzing the fourth element, the Fifth Circuit noted that previous Supreme Court cases involving a single moment of sale (Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios (1984) and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios v. Grokster (2005)) did not control because the plaintiffs’ theory of liability was “not based on Grande’s knowledge about its subscribers’ likely future activities after the moment of sale, but rather on Grande’s knowledge of its subscribers’ actual infringements based on its ongoing relationship with those subscribers.” Further, unlike Twitter v. Taamneh (2023) (a case in which family members of an ISIS terrorist attack victim alleged that US social media companies aided and abetted ISIS by permitting the group’s members to use the platforms for ISIS’s purposes), here the “direct nexus between Grande’s conduct and the tort at issue permits an inference that Grande’s knowing provision of internet services to infringing subscribers was actionable.”

The district court’s jury instructions – that Grande could be contributorily liable if Grande could have “take[n] basic measures to prevent further damages to copyrighted works, yet intentionally continue[d] to provide access to infringing sound recordings,” were not erroneous, as Grande had access to at least one “basic measure” – terminating services to known, repeat infringers. Following a Fourth Circuit case, BMG Rts. Mgmt. v. Cox Commc’ns (2018), the Fifth Circuit agreed that “supplying a product with knowledge that the recipient will use it to infringe copyrights is exactly the sort of culpable conduct sufficient for contributory infringement.”

Thus, the Fifth Circuit concluded: “because (1) intentionally providing material contribution to infringement is a valid basis for contributory liability; (2) an ISP’s continued provision of internet services to known infringing subscribers, without taking simple measures to prevent infringement, constitutes material contribution; and (3) the evidence at trial was sufficient to show that Grande engaged in precisely that conduct, there is no basis to reverse the jury’s verdict that Grande is liable for contributory infringement.”

However, the Fifth Circuit reversed the jury’s damages award, which was based on the district court’s determination that each of the plaintiff’s infringed sound recordings was eligible for an individual statutory damages award. Instead, “the record evidence indicates that many of the works in suit are compilations (albums) comprising individual works (songs). The statute unambiguously instructs that a compilation is eligible for only one statutory damage award, whether or not its constituent works are separately copyrightable.” Thus, the Court remanded for a new trial on damages.

/>i

/>i