One political committee, one think tank, one consulting firm: it all adds up

The three pillars of what’s often dubbed Newt Inc. — two for-profit groups and one defunct political committee — raked in more than $105 million in revenue and donations from 2001 through 2010 while Newt Gingrich was eyeing a political comeback.

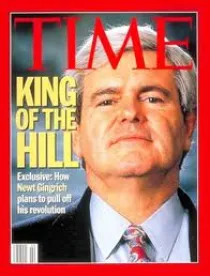

Former House Speaker and Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich Stephen Morton/AP

Today, those groups are attracting new scrutiny as the former speaker appears to be gaining momentum and winning new supporters in the race for the GOP presidential nomination.

Earlier today, the two for-profit groups — the Gingrich Group, a consulting firm, and a think tank, the Center for Health Transformation — responded to a host of inquiries by revealing revenue figures. The organizations said in a statement that from 2001 through 2010 they worked for more than 300 members and clients, many of which are leading health care companies and insurers. The gross revenues from these members and clients came to almost $55 million, the statement said. Gingrich has now reportedly severed ties with both groups.

The $55 million in revenues comes on top of more than $50 million that Gingrich’s political committee, American Solutions for Winning the Future, roped in over about four years before going out of business this summer soon after Gingrich kicked off his campaign for the Republican nomination.

The leading donor to the political committee during these years was multi-billionaire Las Vegas casino owner Sheldon Adelson, who ponied up $7 million.

The health care clients that fueled much of the success of the for-profit groups — some of which have not been previously reported — include: America’s Health Insurance Plans, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, WellPoint Inc., and Johnson & Johnson, according to the Center for Health Transformation’s ’s website. Also on the list: the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the American Hospital Association.

Some of these members paid fees as high as $200,000 a year to join the health center, according to the group. It offered numerous services such as teleconferences, four member meetings per year and member-only website content, op-eds and white papers, according to the center’s website.

Nancy Desmond, CEO of both the Gingrich Group and the health center, stressed in a statement that at the Gingrich Group “we do no lobbying for clients and always make that very clear from the outset.”

The health center, which started in 2003 as a project of the Gingrich Group, is a self-styled think tank “dedicated to the creation of a 21st Century Intelligent Health System that saves lives and saves money for every American.”

Susan Meyers, a spokesperson for the two groups, told iWatch News that “We explicitly and in writing tell members or potential members that we don’t do lobbying and if they’re looking for a lobbyist they need to hire someone else.”

But the website for the health center suggests that its mission and modus operandi may be broader than traditional think tanks. The website boasts, for instance, that among the services it provides members are “advocacy, coalition building and communications to remove roadblocks and accelerate adoption of transformational policies.”

Norm Ornstein, a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute — where Gingrich held a part time perch before his campaign — said in an interview that “if I were to write a Wikipedia definition of lobbying it might not be all that different from their description.” He added that Gingrich’s enterprises “may have avoided lobbying members face to face.”

The two for-profit entities worked closely together, according to two veteran consultants close to Newt Inc. One consultant said that members of the health center were not infrequently referred to the Gingrich Group for strategic consulting services. The Gingrich Group also had many other clients including Freddie Mac, which paid it almost $2 million for several years of consulting work.

Some academic observers wondered whether the new disclosures might hurt Gingrich, who has surged in the polls even after his campaign was damaged by mass resignations just a few months ago.

“He’s trying to depict himself as a Washington outsider, but the financial ties suggest he’s very much an insider,” said John Pitney, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College in California.

Ornstein concurred. “This is like peeling an onion,” he said. The new financial disclosures “raise questions about what value-added Newt and his organizations provided for what are staggering sums of money.”

/>i

/>i