Applicants for design patents should consider claiming functional aspects of their designs in addition to the purely ornamental elements as part of their claiming strategy to achieve the broadest protection for their designs.

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided an appeal recently in Sport Dimension, Inc. v. The Coleman Company, Inc.[1] that addresses the treatment of functional elements when construing the claim of a design patent.

While utility patents protect the way an article is used and works,[2] design patents protect the way an article looks.[3] Though all articles of commerce have some degree of function, the design of an article of commerce is not eligible for a US design patent if the design is purely functional. Such is the case if the overall appearance of the design is dictated by its function. The Federal Circuit recently noted in Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. et al. v. Covidien, Inc. et. al.[4] that the scope of a design patent claim “must be limited to the ornamental aspects of the design.”

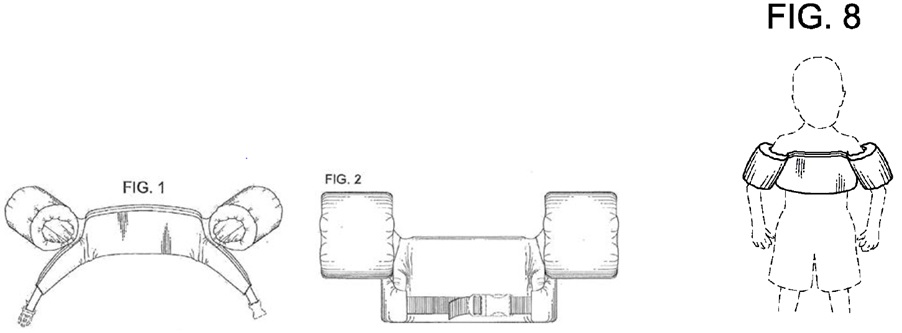

In Sport Dimension, the Federal Circuit found that the design at issue included functional elements, but held that a proper construction included at least some consideration of those elements that should not be completely ignored. At issue in the case was Coleman’s US Design Patent No. D623,714, which claims the ornamental appearance of a personal floatation device illustrated here:

Sport Dimension sought a declaratory judgment that its Body Glove product, illustrated below, does not infringe the Coleman patent:

Finding the left and right armbands and the torso tapering of the Coleman patent to be functional, the US District Court for the Central District of California construed the Coleman patent as claiming the illustrated design but excluding the armbands and torso tapering. That construction led Coleman to move for entry of a judgment of noninfringement so that the Federal Circuit could rule on the claim construction.

The Federal Circuit Decision

While the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court in some respects, it overturned the claim construction and remanded. The Federal Circuit expanded on its decision in Ethicon and endorsed a framework for determining which elements of a patented design are functional. The court borrowed a test from Berry Sterling Corp. v. Pescor Plastics, Inc.[5] that is used for validity purposes when determining whether a design is primarily functional or primarily ornamental.

The Berry Sterling factors include

-

whether the protected design represents the best design;

-

whether alternative designs would adversely affect the utility of the specified article;

-

whether there are any concomitant utility patents;

-

whether the advertising touts particular features of the design as having specific utility; and

-

whether there are any elements in the design or an overall appearance clearly not dictated by function.

Applying the Berry Sterling factors to the facts of this case, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s conclusion that the armbands and side torso tapering served functional purposes. It noted that the armband and torso tapering elements of the patent represented the best available design for such a device, and that Coleman had filed a co-pending utility application that touted those functional features. Still, the court explained that “while a fact finder should not focus on the particular designs of these elements when determining infringement, [it should] focus on what these elements contribute to the design’s overall ornamentation.”[6]

By construing the claim to include the overall ornamental aspects of the design—including the armbands and tapered torso—the Federal Circuit left in place elements of the design that might arguably be found in the accused product. Yet, the court made the point that the overall claim scope is narrow in light of many functional elements, and that the design includes the appearance of three interconnected rectangles as seen in Fig. 2.

Considerations in Light of Sport Dimension

This case highlights the complexities of construing design patents that include elements that are driven to a large degree by function, even when the overall design of which they are a part may be ornamental. Indeed, because all design patents are directed to some article of commerce, there is inevitably some functional aspect to most designs that are subject of a valid design patent.

Design patents remain an important tool for the protection of articles of commerce and consumer products in particular. Careful consideration to the scope of a design patent should be given at the time of filing. For example, rather than avoiding the depiction of functional elements in design patent drawings, applicants may be better served by illustrating those aspects in the context of the overall design. While it may be counterintuitive, claiming more of the article (including elements with functional attributes) may in some circumstance serve to avoid an inadvertent narrowing of the scope of patent protection that might otherwise arise if only certain details of the design were illustrated. Also, by claiming only segments of a particular design, prior art related to those segments may be given greater weight than if the overall design was claimed.

In light of Sport Dimension, other recent design patent decisions, and future decisions that are sure to follow, filing applications with multiple embodiments or filing multiple applications for a design concept with varying degrees of scope are often preferable methods for achieving the broadest protection of the design.

[1] No. 2015-1553 (Fed. Cir. 2016)

[2] (35 U.S.C. § 101)

[3] (35 U.S.C. § 171)

[4] 796 F.3d 1312, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2015)

[5] 122 F.3d 1452, 1455 (Fed. Cir. 1997),

[6] Sport Dimension, slip op. at 10.

/>i

/>i