The popularity of drones has exploded, with investment in the technology becoming increasingly commonplace for news agencies, law enforcement, and private companies.

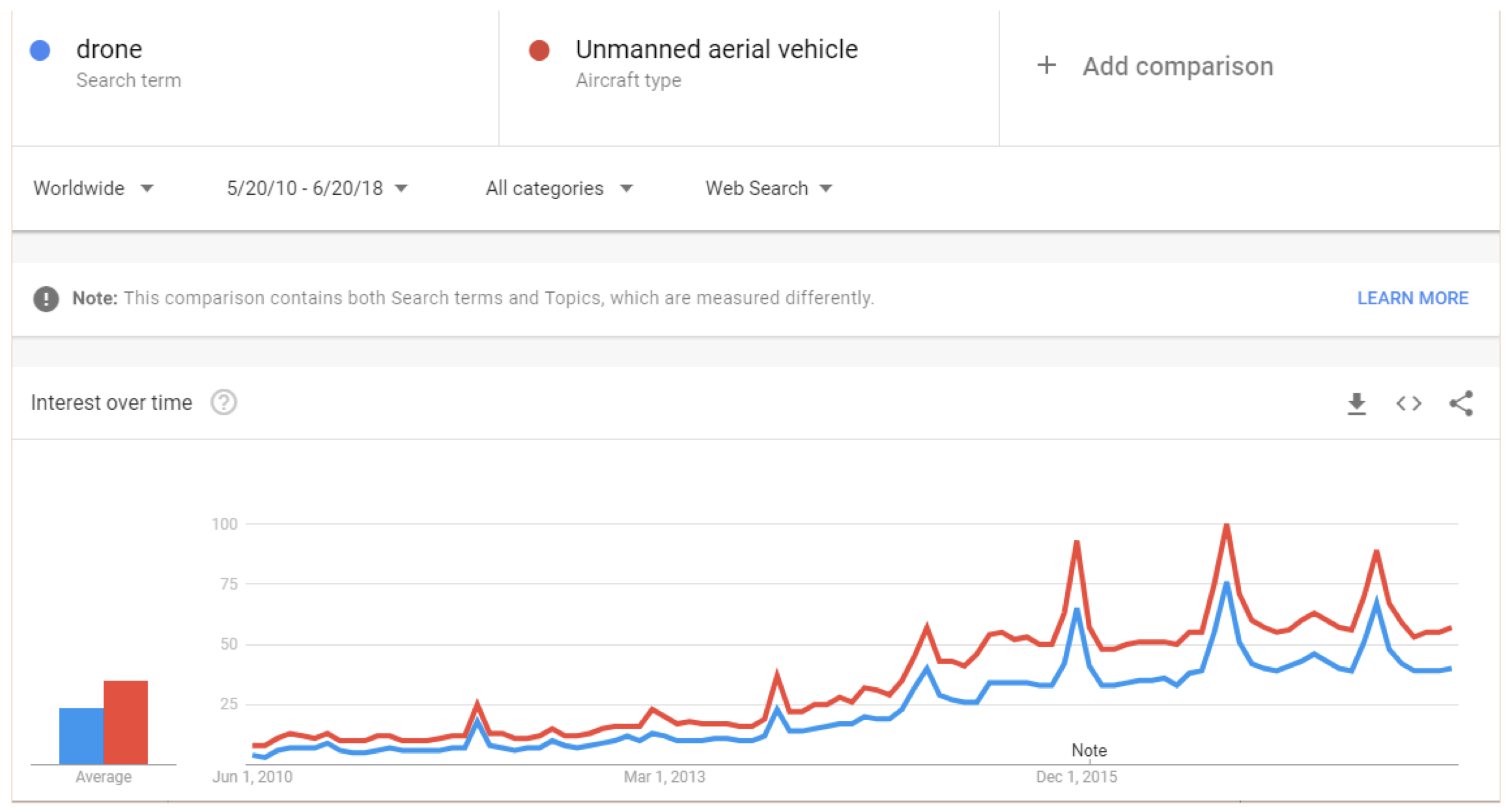

The pace of new innovations related to drones has risen in recent years, with companies like Amazon investing in R&D and new technologies such as its storied jellyfish-style drone, as it seeks to mechanize its supply chain, and Google reporting exponential growth in the popularity of related search terms in the past five years. We have noticed an uptick in interest from our own clients across the AmLaw 100, as they consider expert witness needs for their drone-related IP and regulatory matters.

The Consumer Technology Association estimated that individuals alone bought 2.4 million hobbyist drones in 2016, more than double the 1.1 million sold in 2015.

The Consumer Technology Association estimated that individuals alone bought 2.4 million hobbyist drones in 2016, more than double the 1.1 million sold in 2015. Those figures include drones that do not need to be registered with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Even using a narrower definition, the FAA has registered more than 1 million drones as of June 2018, and expects the number to grow to 4 million by 2021. The FAA further projects about 7 million drones of all types flying in U.S. skies by 2020.

Who Regulates Drones?

While waves of patent disputes may be hovering on the horizon for drone-related technologies as the innovations advance further into mass adoption and commercial use, a pivotal question looms: Who gets to regulate drones? Where can they fly, who can fly them, and when and what steps must be taken to register them with government authorities?

By way of background, under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, federal laws trump conflicting state or local regulations. Principles of preemption govern the extent to which state and local laws still apply when a federal law regulates a particular sphere of activity. See Murphy v. Nat'l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 138 S. Ct. 1461, 1480 (2018).

There are three types of preemption — express, field, and conflict. Express preemption exists when a federal statute expressly bars states and other governmental authorities from legislating in a particular area assigned to the federal government.

Field preemption occurs where the bar against State regulation is not explicit, but nevertheless federal law regulates a field so comprehensively that one can infer that Congress intended to fully occupy the field, and leave no room for parallel State regulation. In a nutshell, field preemption is express preemption by implication.

Finally, conflict preemption applies when federal law leaves room for state regulation, but a particular State regulation imposes duties, or grants rights, that are inconsistent with federal law, thereby creating a conflict.

Regulating Drone Operation

On September 21, 2017, a Massachusetts District Court evaluated whether an ordinance passed by the City of Newton, Massachusetts, regulating drone operation within Newton city limits, was preempted by inconsistent federal regulations governing drones. Singer v. City of Newton, 284 F.Supp.3d 125 (D. Mass. 2017).

Under federal law, the United States Government has exclusive sovereignty over the airspace of the United States. While this does not preclude states or municipalities from passing valid aviation regulations, where a state’s exercise of its police power infringes upon the federal government’s regulation of aviation, state law is preempted.

In 2012, Congress directed the FAA to develop a plan to integrate drones into the national airspace. The FAA complied by issuing regulations that, among other things, mandates registration of commercial (but not hobbyist) drones and imposes certain operational restrictions, including keeping the drone within the visual line of sight of the operator or a designated observer, and below an altitude of 400 feet above ground level or within a 400 foot radius of a structure.

In August 2015, concerned about protecting the privacy interests of Newton’s residents, Newton’s City Council passed an ordinance that imposed certain registration requirements on drone owners, and banned (i) the use of drones below the altitude of 400 feet over private property without the express permission of the property owner, (ii) flying the drone beyond the visual sight of the operator, and (iii) operating the drone over Newton city property without the City’s prior permission.

Michael Singer, an FAA-certified drone pilot who operated multiple commercial drones in Newton, sued to invalidate the ordinance as preempted by the FAA’s regulations.

The Court found that field preemption did not apply since the FAA’s regulations contemplate a measure of state or local regulation of drones, thereby indicating that there was no intent for the federal government to fully occupy the field of drone regulation.

The FAA has registered more than 1 million drones as of June 2018, and expects the number to grow to 4 million by 2021.

The Court concluded, however, that several subsections of Newton’s ordinance were conflict preempted because they were inconsistent with the FAA’s regulations. For instance, the ordinance’s registration requirements conflicted with the FAA’s expressed intent to be the exclusive authority for registration of drones. Additionally, the restriction against flying a drone over Newton city property did not contain an altitude limit, and thereby effectively regulated the national airspace. At the same time, the ordinance sought to bar operation of drones below 400 feet over private property, which frustrated FAA regulations allowing operation below 400 feet.

Conclusion

The City of Newton initially appealed the District Court’s decision, but later settled. Surprisingly, there have been no further reported decisions concerning state and local drone regulation since Newton was decided.

Drone attorney Jonathan Rupprecht notes that while Newton is only binding in Massachusetts federal court, courts in other jurisdictions may likely follow its rationale and invalidate state and local drone laws that conflict with federal drone regulations. Therefore, elected officials considering passing a new drone law would be well-advised to consult Newton to determine whether a proposed law passes muster under preemption principles.

Photo 1 by Jason Blackeye on Unsplash

Photo 2 by George Kroeker on Unsplash

Photo 3 by Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash

/>i

/>i