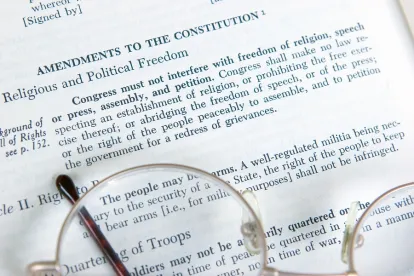

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” — The First Amendment

The Constitution’s First Amendment is arguably the backbone of American democracy. Freedom of speech provides the foundation upon which the remainder of the rights are derived and supported. Its implications, however, are a notorious (and endless) bunch. They are often quite difficult to surmise and have engendered some of the fiercest debates in the centuries’ old legal history of America.

Bar Association Fees and Its Popular Discontents

Trade unions in the United States became significant as a result of the Industrial Revolution. At that time, any single worker might struggle to gain acceptable working conditions for themselves from their employers. They recognized that as a group they would wield far more influence. These bands of workers, or unions, utilized that power in collective bargaining to impact labor provisions time and again.

Industrial workers are not the only ones to unionize, of course. Another, related type of organization is the state bar association, which attorneys in many states are required to join in order to practice law in that jurisdiction. These lawyers are then compelled to pay a fee each year. The bar uses the proceeds from member dues for any number of purposes, from the banal and administrative to the emotional and political. It is the latter to which the courts and bar associations now turn their collective attention.

The Supreme Court Bars Mandatory Union Fees

There are two recent and relevant rulings that require assessment vis-a-vis compulsory state bar association fees. The first is Fleck v. Wetch, a case in which the focus was on an attorney from North Dakota named Arnold Fleck. He argued that he did not need to pay obligatory dues or bar association fees to his state bar because the two parties held different political leanings. Further, the bar, he said, could use his membership proceeds to advance an agenda with which he did not himself agree, and this violated his First Amendment rights.

The Supreme Court found “that an integrated bar can, consistent with the First Amendment, use a member’s compulsory fees to fund activities germane to ‘regulating the legal profession and improving the quality of legal services,’ but not to fund non-germane activities the member opposes.” In this, the court unambiguously agreed with Fleck.

The second related ruling comes from Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). With regard to bar association fees being used for political means, Justice Alito wrote, “We conclude that this arrangement violates the free speech rights of nonmembers by compelling them to subsidize private speech on matters of substantial public concern.”

In this ruling, the Supreme Court reversed its conclusion regarding Abood v. Detroit Board of Education from 1977. That case distinguished two different sorts of compulsory dues. In the first sense, the court opined that requiring both members and non-members to pay fees to a union that used said money for political business was in direct violation of the First Amendment. However, the court maintained that it was still constitutional to force even non-members to provide payments that supported collective bargaining for the betterment and welfare of the working constituents, both member and non-member alike.

With each of these rulings, by extension, the status of state bar associations came into the crosshairs. The most recent ruling directly reverses prior judgments. As a result, some wonder whether these associations can continue to exist — or to function efficaciously — without the regularly paid dues by members of that state. With regard to Fleck, the court stated, “The North Dakota system is precisely designed to restrict individual choice and maximize the political influence of the State Bar itself.” Further, Alito wrote, “Compelling individuals to mouth support for views they find objectionable violates that cardinal constitutional command, and in most contexts, any such effort would be universally condemned.”

Conclusion

Not all bars require every lawyer in their state to join in order to practice law. Even now, these kinds of bar associations will continue to exist (while funds last) and function as they have in the past. It is only those that mandate membership for all attorneys that are affected by the recent ruling. The only certainty is that change is afoot for bar associations, especially those of a compulsory nature.

/>i

/>i