Abortion is a hot-button social, theological, and legal issue in the United States. Since the 1973 decision handed down by the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade, judges, legislators, medical practitioners, clergymen, and the average citizen alike have attempted to rectify the issue one way or another. Roe has remained well-settled law, to the satisfaction of some and to the dismay of others. It remains a highly politicized issue, and shows no sign of going away as one of the platform shaping issues in the years to come.

The question that remains is: What will become of the Roe v. Wade decision in the future? Specifically, is there any evidence to support the overturning of Roe in the coming years?

This work is intended to predict the future by first delving into the past. First, the history of abortion jurisprudence, or lack thereof, will be explored chronologically leading up to Roe. Second, the major Supreme Court decisions that have shaped the Court’s ruling in Roe will be analyzed. At last, the future of abortion rights will be predicted by looking into advances in the medical field, the make-up of the Supreme Court, and the possible impact of the Trump administration.

I. LEGAL HISTORY PRE-ROE

Surprising to many, abortion and reproductive rights were in existence long before Roe. In fact, the United States borrowed its original ideas and laws from Britain.[i]

A. British Common Law

The first mention of abortion law in the United Kingdom goes back to the 13th Century. [ii] The law provided, and remained static until the early 1800’s, that abortion was legally acceptable until the “quickening” of the child. Id. Quickening took place when the pregnant female was able to perceive the child’s movements in the womb.[iii] This was interpreted to mean that the child had gained a soul.[iv] Punishment for committing a post-quickened abortion varied, until the early 19th Century, when the offense became punishable by death. Id. Through the remaining years, abortion laws changed often with the notion of quickening, or the new term “viability,” being at the crux of the issue. Id.

B. American Jurisprudence

The American colonies, and then states, borrowed Britain’s “quickening” rule in their earliest days.[v] This remained the widely accepted rule for nearly the first century of the new nation’s existence. Abortions before the time of quickening were accepted and commonly performed. Id.

In the mid-1800’s, America broke away from its British influence regarding abortion. Massachusetts became the first state in the Union to address the issue by making the practice illegal.[vi] Further, the 1873 Comstock Act, passed by Congress, criminalized “obscene” behavior, including but not limited to, abortion, contraceptive use, and other such acts that would “threaten a woman’s chastity.” Id.

A couple of motivating factors have emerged concerning why Massachusetts and other states decided to branch off from common law influence and rule abortion and other “obscenities” illegal at that time in history. The first factor includes fear of immigrant children being born at higher rates than that of “native” Anglo-Saxon children.[vii] The second motivating factor, and perhaps the more scientific of the two, concerns the high risk of such a complex medical procedure during that time in history. Id. By the turn of the 20th Century, all states had outlawed abortion.[viii]

The issue of abortion seemingly stayed static for much of the 20th Century. During the 1960’s; however, a number of states began to repeal their criminalizing abortion laws after the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code set grounds for legalizing abortion in cases of rape, incest, other felonious intercourse, severe mental or physical defects, or if the pregnancy would gravely impair the woman’s physical or mental health. Id. The Model Penal Code instituted additional stipulations, such as certification by two different physicians justifying the abortion. Id. By 1970, a number of states permitted at least first trimester abortions. Id. It was during March of this same year that a Texas woman with the alias “Jane Roe” would file a federal action after being denied an abortion pursuant to state law.[ix]

II. Roe to Hellerstedt

A. Roe v. Wade

“Jane Roe” was a pregnant, unwed Texas woman who sought to terminate her pregnancy. Id. Texas law, in pertinent part, made it a crime to “procure an abortion,” or to attempt one, unless it was for the purpose of saving the life of the mother. Id. Since her life did not appear to be threatened by her pregnancy, she was unable to get an abortion in Texas. Due to her financial hardships, she was unable to travel to another state that allowed her to legally terminate her pregnancy. Id.

Roe filed suit against the District Attorney of the jurisdiction for injunctive relief on behalf of herself and all future pregnant women seeking abortions. Id. She cited, among other things, that the Texas statute was unconstitutionally vague, and that it violated her right to privacy under Griswold v. Connecticut, the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments.[x] Id. District Attorney Wade argued, inter alia, that the Texas statute should be upheld because it discouraged illicit sexual conduct, protected the mother from hazardous medical procedures, and protected prenatal life. Id.

The Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, ultimately held that the Texas statute was unconstitutionally broad.[xi] While the Court dismissed Wade’s arguments, it refused to rule that a woman’s right to abortion is absolute.[xii] Applying a strict scrutiny standard, the Court chose to bifurcate the issues of the mother’s right to health and the rights of the “potential life.” Id. Concerning the former, a state may only regulate abortion after the first trimester (approximately 12 weeks) of the pregnancy. Id. Concerning the latter, the state may regulate abortion after the “point of viability” (approximately 24-28 weeks). Id. The “point of viability” rule bears a striking resemblance to the quickening rule inherited centuries earlier from British common law. The Court’s reasoning for the point of viability rule is that “the fetus then presumably has the capability of meaningful life outside the mother’s womb.” Id.

Since the 1973 decision, Roe v. Wade has virtually become synonymous with abortion law in the United States. Several schools of thought have surfaced on the issue, with two main ideologies emerging: the battle between those who are “pro-choice” and those who are “pro-life.” The decision in Roe v. Wade ironically “breathed life” back into the issue of abortion. Though it is viewed as the he paramount case on the issue, it is not the only case to shape the way abortion is viewed in the judiciary today.

B. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey

Nearly two decades after the Court’s decision in Roe, it found itself with a new opportunity to shape abortion jurisprudence. This opportunity came out of Pennsylvania when a state law concerning abortion was Constitutionally challenged.

The law at issue required a mandatory 24 hour wait period before attaining an abortion, consent of at least one parent to the abortion, and notification of a husband by wife regarding the procedure.[xiii] The plaintiffs argued that these requirements were unconstitutional on their face, and could not be upheld without overturning the Roe decision. Id. The Court ultimately rejected this argument, upheld the standards set forth by Roe, and declared only the requirement for notification of a husband by wife unconstitutional. Id.

The Court broke the Roe decision down into three parts: 1) the right of the woman to choose abortion before viability without undue interference by the state; 2) the state’s power to restrict abortion after viability, with exceptions for endangerment to health or life of the mother; and 3) the state’s legitimate interest in protecting the health of the woman and the life of the fetus that may become a child. Id. The Court echoed the standard that the line should be drawn at viability. However, the strict scrutiny standard applied in Roe gave way to a new standard of review: the “undue burden” test. Id. This test asks whether a state has placed “a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion before the fetus attains viability.”[xiv] The idea behind such a standard is to prevent a state from essentially keeping the abortion from taking place by placing a time restraint that could put the woman over the time in her pregnancy when the fetus is considered viable.

While the decision in Casey was seemingly a victory for pro-life advocates in that it placed certain roadblocks in the path of a woman seeking an abortion, it upheld all of the major parts of the Roe decision. And while Casey is not viewed in the national abortion discussion as being of the same importance as Roe (i.e. pro-life advocates are not as concerned with overturning Casey), it put in place a standard for analyzing abortion laws that has lasted over two decades.

C. Carhart v. Gonzales

In 2007, the Supreme Court once again faced the issue of abortion and women’s reproductive rights when the 2003 Federal Partial-Birth Abortion Ban was challenged.[xv] Partial-birth abortion, according to the federal ban, occurs when "the entire fetal head [...] or [...] any part of the fetal trunk past the navel is outside the body of the mother.”[xvi] Ultimately, the Court held in a 5-4 decision that the Ban was Constitutional, and did not impose an undue burden on a woman seeking an abortion. Id.

Even though the Carhart decision was seemingly a loss for pro-choice advocates, two important concepts remained intact: the rule of Roe was not affected and the undue burden standard from Casey was the anchor of the analysis.

D. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt

Earlier this year, Texas House Bill 2 was challenged in the Supreme Court. Bill 2 had passed the Texas Legislature and was nearing its effect date when it was challenged by a group of plaintiffs.[xvii] Bill 2 had two requirements: that an abortion provider should possess “admitting privileges” to a hospital no less than 30 miles away from where the abortion would take place, and that the abortion facility should have the same minimum standards as a surgical center. Id. Champions of the Bill contend that the added requirements would ensure that abortion procedures would render safer results for women. The District Court granted an injunction stopping the Bill due to the undue burden it placed on a female seeking an abortion. Id. The Court of Appeals overturned the injunction and the Supreme Court granted writ of certiorari shortly after. Id.

The Supreme Court used a number of findings from the District Court to shape its decision. In pertinent sum, the District Court found that one-fifth of Texas’ population consists of reproductive age women; about 15% of pregnancies in Texas end in abortion; there were 40 abortion clinics in Texas prior to the passage of House Bill 2; after passage of House Bill 2, there were only 20 clinics left open; once in full effect, there would only be 7 or 8 clinics that met the requirements set forth by the bill. Id. While advocates of the bill cite safety concerns as the driving force, others assert that the requirements were nothing more than an attempt to place requirements that were impossible for 80% of the state’s total clinics to meet.

Once again using the Casey standard, the Court agreed with the latter assertion and determined that House Bill 2 placed an undue burden on women seeking nonviable abortions in the state of Texas. Id.

III. THE FUTURE

A. Medical Advancements

The medical field that caused abortion to become more widely ascertainable could ironically be the field that causes its decline. Each of the Supreme Court cases concerning abortion and women’s reproductive rights were shaped around the issue of when life perceivably begins. On one hand, many pro-life advocates argue that life begins at conception, or the fertilization of an egg. On the other hand, many pro-choice advocates argue life begins when the child exits the womb through the birth canal. The Supreme Court in Roe seemed to take an approach that split the two perceptions with the view that viability - the point in which the child could survive outside of the womb, “albeit with artificial aid” - is the time life begins, and the time the child has rights of his or her own.[xviii]

The point of viability was described in Roe as generally occurring around 28 weeks, but sometimes as early as week 24. Id. It would logically follow that abortion would be legally ascertainable until the 24 week mark in the pregnancy. In at least one instance, however, a child has been born before the 24 week mark in the United States since the Roe decision. Amillia Taylor was born in a Miami Hospital in late 2006, just 21 weeks and 6 days into her mother’s pregnancy.[xix] Amillia’s mother lied to doctors and told them she was 24 weeks pregnant, in order to keep the question of the age of viability out of the equation. Id. Amillia required constant monitoring by a doctor and staff during her stay at the hospital. She needed oxygen and asthma medication, among other things, to allow her lungs to properly form. Id. She undoubtedly would not have survived but-for modern advances in the medical field, and she has single-handedly sparked the debate of lowering the age of viability for the past several years. Id.

Further complicating the age of viability dialogue is the ever approaching possibility of an artificial uterus being introduced into the medical field. While the lack of understanding surrounding the placenta has placed a dampener on efforts to build an artificial uterus in the near future, talks about the possibility of such a unit is at least on the horizon.[xx] Astrobiologist David Warmflash admits that scientists may have jumped the gun in talking about the future of artificial wombs, as such devices may be decades in the making. Id. However, decades as it may be, the invention of an artificial womb will potentially take the mother completely out of the birthing process in many cases. Such an advance in the medical field is sure to spin the viability debate on its head, but it must be a sale that the Justices on the Supreme Court are willing to buy when the time comes.

B. The People

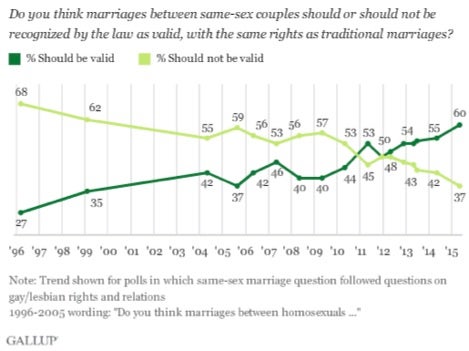

An important and fascinating variable in the equation concerning abortion is that of the American public. Many times, landmark decisions that change the direction of a given issue are handed down from the Supreme Court around the same time the public or social perception of that issue changes.[xxi] For instance, 68% of the general public felt like marriage between two persons of the same sex should not be valid in 1996.[xxii] By the year 2012, that number had fallen to 48%, with 50% of poll participants believing gay marriage should be legal. Id. Today, 60% of the public supports same-sex marriage, while only 37% believe marriage should be limited to one man and one woman. Id. In 2015, the polls showed nearly a 60/40 split between those in favor or same-sex marriage and those who were against it. Id. That same year, the Supreme Court handed down the decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, holding that same-sex couples were afforded the same rights under the 14th Amendment Due Process Clause as heterosexual couples on the issue of marriage.[xxiii]

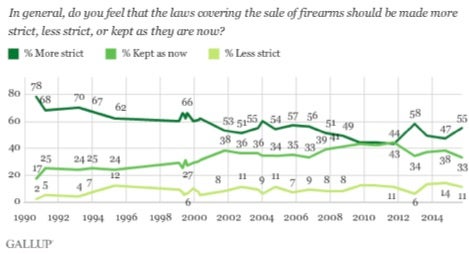

Following a similar trend on the public’s perception compared to landmark decisions, polls show that 78% of the general public favored more strict gun laws in the year 1990, while only 17% favored less strict laws.[xxiv] The percentage of those who favored stricter gun laws steadily declined throughout the 1990’s and was down to 51% by 2003. Id. Those who favored less strict laws rose from 2% to 11% in the same time frame, while those who wanted the laws “kept as they are now” grew from 17% to 36% in the same number of years. Id. Those numbers remained steady throughout the 2000’s. Id. In 2008, the Supreme Court decided District of Columbia v. Heller, holding that a District of Columbia law that required guns to be registered and kept disassembled in the home violated the protection granted to citizens by the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution.[xxv]

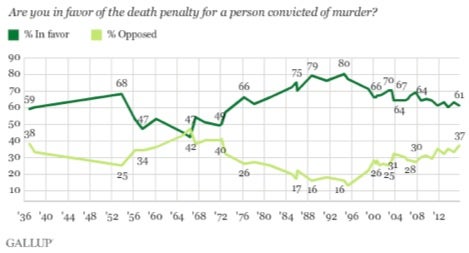

Furthering this analysis as a sort of “control” is the issue of capital punishment. In 1988, 79% of the public favored the death penalty, while only 17% opposed it.[xxvi] Today, though that number has fallen to 61% in favor and 37% opposed, the vast majority still favors capital punishment. Id. While many cases have emerged shaping capital punishment jurisprudence[xxvii], no decision has led to the demise of the death penalty altogether. If the current trend keeps going in the direction it is, however, it could be that the death penalty will be just as popular as it is not in the next decade and a half.

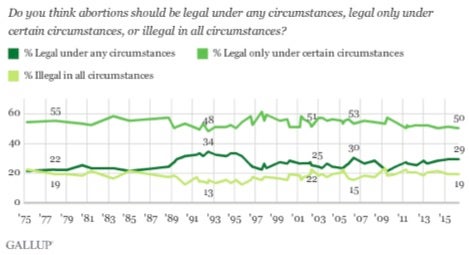

On the issue of abortion, the public perception has remained overwhelmingly static for the past 40 years.[xxviii] In 1977, just four years after the Roe decision, 19% of people felt that abortion should be illegal under all circumstances. Id. Today, that number is identical, with its low point being 13% and its high being 22%. Id. In 1977, 22% felt that abortion should be legal under any circumstance. Today, that number is 29%, and is 5 points below its all time high of 34% in 1993 (the same year as the Casey decision). Id. Those who feel that abortion should be “legal under certain circumstances” was 55% in 1977 and is 50% today, with 55% being the high point, and 48% being the low (again the same year as Casey). Id. In short, the public view of abortion is virtually the same today as it was 40 years ago. Comparing this to the trends explored on the topics of same-sex marriage, gun control, and capital punishment, if any change occurs to abortion jurisprudence in either direction, it will happen without the weight of the public behind it, an unlikely result.

C. The Players

Irrespective of medical advancements being made, the future - at least the very near future - of abortion jurisprudence rests in the hands of the 8 sitting Justices of the Supreme Court of America. The Constitution quite literally means whatever the majority of those Justices interpret it to mean. To understand what changes, if any, will be made in respect to abortion and women's reproductive rights, it is important to understand where each of the Justices fall on the issue.

Each of the current sitting Justices were present for the Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt case earlier this year. Each of the Justices, minus Justices Sotomayor and Kagan were present for the Gonzales v. Carhart case in 2007. The only two Justices who were on the bench for Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey in 1992 were Justices Thomas and Kennedy.

In summation, if the makeup of the Court remains constant, the decisions in Roe and Casey are very comfortable right where they are. It is important to note that the vacancy left by the death of Justice Scalia has not been filled to this point. Yet, even if the newly appointed ninth Justice proves to be on one side of the abortion issue or the other, it will not be enough to tip the scale in either direction.

As of now, Clarence Thomas is the only Justice who has expressed a wish to overturn Roe and send the issue to the states. Justices Alito and Roberts lean toward loosening the reigns on states, but neither have expressly stated an interest in overturning Roe or Casey, even though their votes are consistently pro-life. Justice Kennedy has proven to go either way on abortion, and would likely not overturn either case. Justices Kagan and Sotomayor are presumably pro-choice advocates, given their vote in Hellerstedt, but it is too early to tell for certain. Then, Justices Breyer and Ginsburg have fought to protect a woman’s right to an abortion at every turn. While possibilities are endless and it is never certain which way a Justice will vote,[xxix] it seems more likely than not that abortion jurisprudence is safe where it is as long as the Court maintains the characteristics it possesses now.

D. Playing Politics

All of this poses the question of what exactly will happen to the make-up of the high Court in the future. To date, 2 Justices are over the age of 80, 1 is 78, 2 are in their late 60’s, and the remaining 3 are below 62. Given the recent results of the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump will have the sole discretion of who to appoint to the Court at least until the end of 2020. Absent a vote being heard on current nominee Merrick Garland before the new Executive takes office, which is very unlikely at this point, it is realistic that there could be up to four new appointments in that time frame.

The conducting of this research takes place at an interesting time, since the question of who will be the new president has literally just been answered. Though it is uncertain who would truly be nominated, president-elect Trump has submitted the names of several Justices he will seek to put on the bench.

President-elect Donald J. Trump has released a list of 21 possible candidates for appointment to the Supreme Court.[xxx] The list is full of some very qualified, conservative leaning jurists, from Federal Appeals Courts to state Supreme Courts. See Id. Most notably, brothers Mike and Thomas Lee of Utah each made the list. Mike is a U.S. Senator, and Thomas is an associate Justice on the Utah Supreme Court. Each of the brothers have been advocates of returning the right to regulate abortion to the individual states for consideration.[xxxi] Judge William H. Pryor, former Attorney General of Alabama and now Judge for the Eleventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, also made the list.[xxxii] He nearly did not make it to the Court of Appeals bench; however, since his nomination was filibustered after his comment that Roe v. Wade was the “worst abomination in the history of Constitutional Law.”[xxxiii] Steven Colloton, a Judge for the 8th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, is on the list, and has a history with abortion proceedings. Id. He voted to uphold a South Dakota law that required women seeking abortions to be advised that they were at an increased risk of suicide. Id. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge, Raymond Grounder is also no stranger to the issue. He penned a dissent that said a South Dakota law requiring doctors to advise women seeking abortions that they were “terminat[ing] the life of a whole, separate, unique, living being” did not impose an undue burden on the woman. Id. The list goes on.

Intervening variables run rampant with this scenario, however. Appointments only arise when seats are vacated, and only one vacancy is guaranteed during this term. Even though a number of the Justices are far beyond retirement age, there is no guarantee they will make the decision to leave within the next four years. To date, there is one vacancy, and a nominee is already in place for consideration, but it is now unlikely that Merrick Garland will be considered. Further, just because a president nominates a replacement, it is not guaranteed that the Senate will accept, or even consider, the nomination. However, it is worth pointing out that for the next two years, the Senate is in Republican control, as is the Executive branch. Nothing in the Constitution mandates a hearing for each nominee[xxxiv], but this is a golden opportunity for Republicans to get together and fill Justice Scalia’s seat with a like-minded Justice.

If Senate Republicans maintain uniformity, and especially if they remain in control after the midterm elections of 2018, an openly pro-Roe nominee will likely have a tougher time being accepted to the bench. If one of the aforementioned potential nominees are accepted to replace Scalia, the Court will likely find itself right back in the position it was in regarding abortion before Scalia’s death. However, if the Court loses Justices Ginsburg, Kennedy, and/or Breyer in the near future (ordered by age), and those Justices are replaced with individuals from Trump’s list, the Court will shift closer to an anti-Roe influence than it has been in recent history. If all three of these named Justices are replaced by members of Trump’s list, and the rest of the Court remains the same, there will be a pro-life majority for the first time since Roe. It is not guaranteed; however, that this scenario would lead to the overturning of Roe. Of course, anything can happen on this issue including, but not limited to, death or retirement of one of the younger Justices, survival or lack of retirement by one or all of the named Justices, a stalemate from the Senate on the nominee, or a nominee that is unexpectedly pro-Roe. At this juncture, only time will tell.

IV. CONCLUSION

The issue of abortion is a very complex one. It is not a new issue, as its roots far outdate the existence of the United States. The newly formed country adopted Britain’s “quickening” rule, but that gave way to safety and theological concerns rendering the procedure illegal. The states maintained control within their respective bounds until Jane Roe won her Supreme Court case in 1973, creating a uniform set of rules based upon a trimester system. This remained constant until Casey provided the new “undue burden” standard in 1992. The Court then again revisited the issue using the undue burden standard in both Gonzales and Hellerstedt. Though the Justices in the respective majority of each case have had the opportunity, they have made no mention of overturning Roe and returning the refusal power to the individual states.

Though medical advancements are on the rise at a rapid pace, the invention of an artificial womb is not realistic, as many have falsely expected. However, there have been instances where children have been born, and survived, before the point of viability. Gallup polls conducted over the course of four decades do not make clear whether “pro-choice” or “pro-life” is heavily favored by public support. Most of the time, there is a clear choice among the people before a longstanding precedent is overturned by the Court.

As it stands, there are more Supreme Court Justices who lean toward defending Roe than the alternative. After the death of Justice Scalia, only one Justice has explicitly supported overturning Roe. While there are at least two Justices who have remained silent on the issue, but voted in a way consistent with being pro-life, a majority of five Justices are needed to change what most consider “well-settled law.” The future is unclear; however, since the age of at least three Justices is above or near 80, and a new president will determine what sort of jurists are selected to fill vacancies, if the Senate even allows such a thing to take place.

In all, there is no definite answer to whether Roe, Casey, or other abortion cases will be overturned in the near future, but given these findings, the road is a very long and winding one for those who wish to return the issue back to the individual states for consideration. The proverbial stars will have to align for pro-life advocates to get their wish, and while rendering abortion illegal is more possible now than it has been, much has to happen in a short amount of time for such a thing to take place.

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

APPENDIX D

[i] Family Law: Cases, Materials and Problems Third Edition by Peter Swisher, Anthony Miller, and Helene Shapo. 2012. P. 229.

[iii] Family Law: Cases, Materials and Problems Third Edition by Peter Swisher, Anthony Miller,and Helene Shapo. 2012. P. 229.

[vi] Family Law: Cases, Materials and Problems Third Edition by Peter Swisher, Anthony Miller,and Helene Shapo. 2012. 229.

[viii] Family Law: Cases, Materials and Problems Third Edition by Peter Swisher, Anthony Miller,and Helene Shapo. 2012. P. 229

[ix] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

[x] Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). (Held that state law prohibiting distribution of contraceptives violated right of privacy under due process clause).

[xii] Roe, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

[xiii] Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

[xv] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

[xvii] Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. ___ (2016).

[xviii] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

[xix] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1021034/The-tiniest-survivor-How-miracle-baby-born-weeks-legal-abortion-limit-clung-life-odds.html

[xxi] See http://www.gallup.com/poll/183272/record-high-americans-support-sex-marriage.aspx; http://www.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx; http://www.gallup.com/poll/1606/death-penalty.aspx. Compare these polls in conjunction with the timing of Obergefell; District of Columbia v. Heller; and the lack of a Supreme Court decision concerning capital punishment; respectively

[xxii] http://www.gallup.com/poll/183272/record-high-americans-support-sex-marriage.aspx. See Also APPENDIX A.

[xxiv] http://www.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx. See Also APPENDIX B.

[xxvi] http://www.gallup.com/poll/1606/death-penalty.aspx. See Also APPENDIX C

[xxvii] Williams v. Pennsylvania, Kansas v. Carr, & Lynch v. Arizona.

[xxviii] http://www.gallup.com/poll/1576/abortion.aspx. See Also APPENDIX D

[xxix] See National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. ___ (2012). (Chief Justice Roberts, to the surprise and chagrin of many Republicans, voted to essentially uphold the Affordable Care Act. This illustrates that the Justices don't always vote the way their respective “party” would expect them to vote).

[xxx] See https://www.donaldjtrump.com/press-releases/donald-j.-trump-adds-to-list-of-potential-supreme-court-justice-picks

[xxxiv] See the United States Constitution

/>i

/>i