On July 15, 2014, the Department of Defense (“DoD” or “Department”) issued a proposed rule to amend the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (“DFARS”) in order to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of auditing contractors’ accounting systems, estimating systems, and material management and accounting systems (“MMAS”). The proposed rule contains new requirements addressing third party audits of these three business systems, as well as a requirement for contractors to annually self-report deficiencies uncovered in these audits or in internal reviews of their business systems.

The impetus for the proposed rule appears to be the serious backlog of audits to be performed by the Defense Contract Management Agency (“DCMA”). The preamble to the proposed rule cites to a November 2011 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office that highlights DCMA’s reliance on the Defense Contract Audit Agency (“DCAA”) “to assist in determining whether a contractor’s business systems are adequate.” As discussed in the Report, both agencies suffer from high workloads that prevent them from meeting their auditing obligations in the business systems area.

DoD’s proposed solution to this backlog is to outsource some of the auditing responsibilities to third- party Certified Public Accountants (“CPA”) and require contractors to self-report any deficiencies. As discussed below, this approach could reduce DCAA’s and DCMA’s auditing backlog and address industry concerns that the government is too quick to find significant deficiencies in contractor business systems. Such a regulatory scheme is, however, not without risks and costs to contractors.

Background

DoD has focused on contractor business systems in recent years. The Department issued a proposed rule on contractor business systems on January 15, 2010, see 75 Fed. Reg. 2457, and, after significant challenges from industry, issued a revised proposed rule on December 3, 2010, see 75 Fed. Reg. 75,550. Further complicating the issue was a provision in the Ike Skelton National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year (“FY”) 2011 (“NDAA”) that imposed a statutory requirement “for the improvement of contractor business systems.” See Pub. L. No. 111-383, § 893, 124 Stat. 4137, 4311 (Jan. 7, 2011).

As a result of comments received on the revised proposed rule and this provision in the NDAA, DoD reworked the revised proposed rule and issued an interim rule that allowed DoD to withhold payments to contractors with “significant deficiencies” in their business systems. See 76 Fed. Reg. 28,856 (May 18, 2011). The interim rule, which we addressed in a May 2011 E-Alert, defined a significant deficiency as a shortcoming that has a material effect on the reliability of information produced by the system for contract management purposes. The interim rule was an improvement over the proposed rules introduced in 2010 because it limited withholding to 5 percent per business system and 10 percent per contractor; it added a materiality requirement to the definition of significant deficiency; and it excluded small businesses from coverage. The interim rule lowered the threshold for coverage from $50 million down to contracts that are “subject to” the Cost Accounting Standards (“CAS”) (under 41 U.S.C. chapter 15). It also largely retained the previous vague criteria for measuring each individual system’s adequacy.

On February 24, 2012, DoD issued a final DFARS business systems rule. See 77 Fed. Reg. 11,355. Although industry had raised numerous concerns about certain key aspects of the interim rule, DoD made only minor adjustments in the final rule.

The Proposed Rule

The proposed rule issued on July 15, 2014 takes a novel approach to contractor accountability for business systems by “entrust[ing] contractors with the capability to demonstrate compliance with DFARS system criteria for contractors’ accounting systems, estimating systems, and [MMASs], based on contractors’ self-evaluations and audits by independent [CPAs] of their choosing.” Contractors not only have to pay a third party to conduct an audit, but also must disclose to DoD any significant deficiencies discovered during those audits or during internal reviews. Government auditors and contracting officers then review contractors’ self-evaluations and CPA audits at the contracting officers’ discretion.

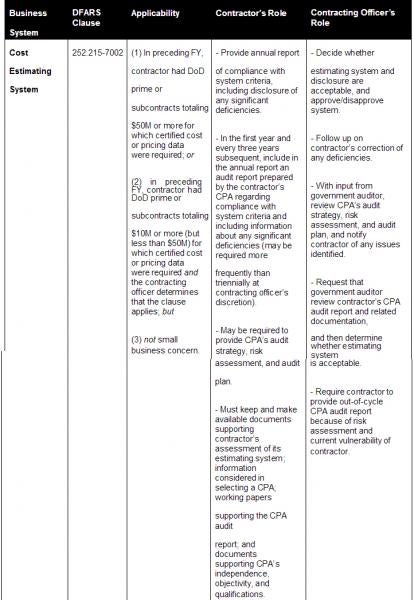

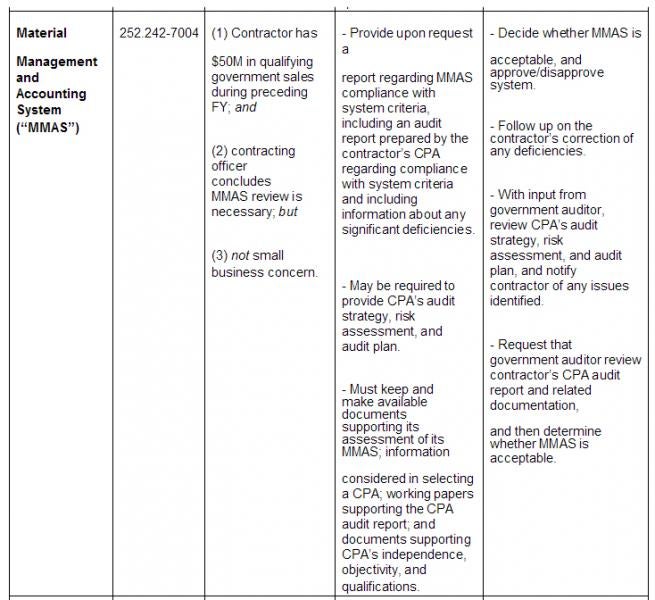

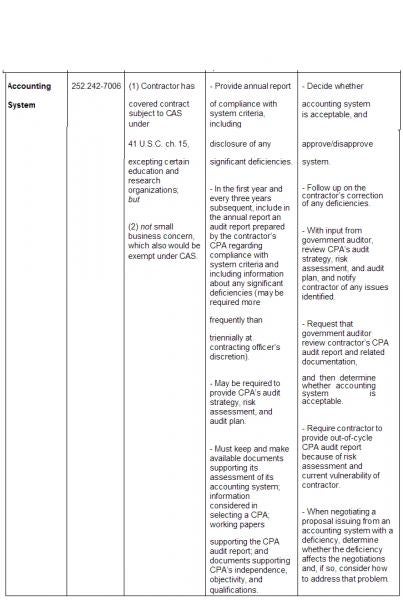

The applicability and application of these proposed reporting and auditing requirements depend on the type of business system. The table below reflects the contours of the proposed reporting and auditing requirements, broken down by business system type. None of the proposed requirements applies to small businesses, and DoD predicts that the proposed rule will have no impact on small business concerns.

As reflected in the table above, although the contractor—together with its CPA—would be responsible for assessing and auditing these three business systems, DoD still would perform its own review on top of the contractor’s review. If a contracting officer opted to perform this review, a government auditor would conduct the first analysis and provide to the contracting officer a report highlighting any significant deficiencies in the contractor’s business system. The contracting officer would then review that report and notify the contractor in writing (an “initial determination”) of his/her findings.

If the contracting officer determined that there were one or more significant deficiencies or that the contractor had not complied with the applicable reporting and audit requirements, the contracting officer would include a description of the problem(s) so that the contractor could remedy them. The contractor then would have thirty (30) days to respond in writing to the initial determination, after which the contracting officer would make his/her “final determination” of whether there were any remaining deficiencies or noncompliance. The contracting officer also would have discretion to withhold payments to the contractor upon a final determination of significant deficiencies or noncompliance with applicable reporting and audit requirements.

The proposed rule also would grant to the contracting officer a significant amount of discretion in determining whether to review a contractor’s business system in the first place, which documents and records to request in performing such a review, whether the contractor and its business systems are compliant, and, if not, the degree of penalty to impose. Although the proposed rule maintains the 5 percent/10 percent cap on withholding as under existing rules, that level of withholding can have a substantial impact on contractor cash flow, particularly given that the contracting officer may impose the withholding on multiple contracts. Moreover, the withholding of payments does not limit the other remedies that the contracting officer may seek against a contractor because of harm caused by a deficient business system.

The proposed rule would not impact DCMA’s existing role in reviewing and auditing contractors’ purchasing, property management, and earned value management systems. It bears noting, however, that payments may be withheld for significant deficiencies under any of the six contractor business systems pursuant to the existing procedures under DFARS 252.242-7005, even though the proposed rule reaches only estimating, MMAS, and accounting.

DoD has solicited written comments in response to the proposed rule, including from small businesses, which must be submitted by September 15, 2014. In addition, DoD will hold a public meeting for interested parties on August 18, 2014.

Impact of The Proposed Rule

The new proposed rule does not address the ambiguities and risks inherent in the current rules governing business systems compliance, but it does create a new dynamic among contractors, their private auditors, and the government. The proposed rule may allow the government to approve a contractor’s systems more quickly, which would be welcome news for the contractor community. The backlog of government audits has been an issue for some time, and some contractors may embrace the use of third party auditors if they are waiting for government resolution on a number of fronts. It is not clear, however, whether this new proposed framework would realize meaningful time efficiencies. Government auditors who review third-party CPA audits may not be inclined to rubber stamp those findings.

Moreover, the required disclosure of deficiencies is troublesome. For one thing, the risk from these types of disclosures is not limited to a potential withholding penalty. For example, a disclosure of a deficiency in an accounting system could lead the government to seek recovery of overcharges that resulted from those deficiencies or take a harder look at a contractor’s cost or pricing data if the contractor discloses a significant deficiency in its estimating system. In addition, should an audit uncover information that puts a company at legal risk, the audit will not have been conducted under a privileged review. For example, if a contractor discloses significant deficiencies in its estimating system, this could prompt the government to scrutinize more closely that contractor’s cost or pricing data submissions. Thus, the disclosure requirement in the proposed rule may be at odds with a contractor’s desire to more fully investigate any issues raised by an audit and could force a quicker resolution to the matter than would be required otherwise under the Federal Acquisition Regulation mandatory disclosure requirement.

/>i

/>i